Handmade paper is more than simply a surface on which to work for such artists as Lynda Benglis, who fashioned the baroque wall piece Aquanot #33 from cast paper, pigments, sparkles and paint. 1980. 46x32x6 inches. Margo Leavin collection.

For millennia, handmade paper remained the province of skilled craftsmen bound by ancient techniques. Now, in a matter of some twenty years, the field has been transformed. Young artisans, university-educated and determined to put their own stamp on a highly traditional craft, have pushed the pulp medium in new directions. Painters, sculptors, and printmakers excited by the aesthetic possibilities of paper have appropriated its substances and processes. Collaborations have blossomed, and the old lines between craft and art have begun to fade. In the international contemporary art world, paper has become a hot commodity.

The current paper explosion has its antecedents in events of the early postwar years. In 1951, at the Betty Parsons Gallery, a show of collages made of handmade paper by Anne Ryan caught the attention of Lee Krasner and her husband, Jackson Pollock. Ryan told the Pollocks about the papermaker who provided her materials, Douglass Morse Howell, and the couple made a beeline for his Westbury, Long Island studio. The fine table damasks of pure linen that Howell used as raw material for his unique papers were, it turned out, an ideal medium for Pollock’s blot-and-stain experiments with drawing inks and washes. The ten drawings Pollock made on sheets commissioned from Howell marked an auspicious modern collaboration between artist and papermaker.

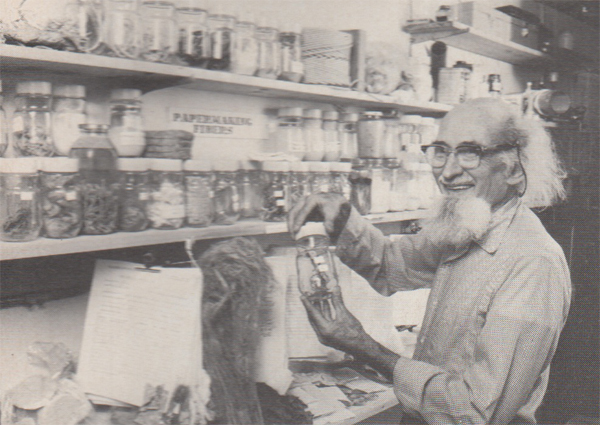

Douglass Morse Howell, one of the pioneers of handmade paper in America and the alchemist of flax and linen, began supplying unique papers to artists such as Jackson Pollack and Helen Frankenthaler in the 1950’s.

A printmaker and writer, Howell had caught the papermaking bug as a soldier in Europe during World War II, when he was assigned to write a history of his batallion. His search for paper and printing facilities led him to the Moulin a Papier Richard de Bas in Ambert, France, a firm founded in the fourteenth century and still one of France’s finest paper manufacturers. By the early 1950s, Howell was supplying artists with lushly textured and tinted sheets for drawing and printmaking.

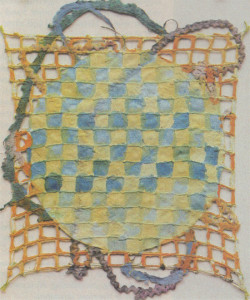

Alan Shields approaches the medium very differently, combining printmaking collage, and sewing in “Intergalactic Swing”, and intricate construction of string, rickrack, and watercolor on handmade paper. 1980-81, Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Tatyana Grosman recognized his genius in the mid-fifties and in 1959 set him to making a 100 percent denim binding and handmade-paper sheets for the first collaboration between poet Frank O’Hara and painter Larry Rivers at the fledgling Universal Limited Art Editions in Islip, Long Island. As legend—and Calvin Tompkins—has it, Grosman saw Rivers and O’Hara dressed in blue jeans and decided that the material would make an ideal substrate for the edition of lithographs and poems entitled Stones. Howell, who is now seventy-seven years old, still manufactures his unique papers at his Riverhead, New York studio. At his retrospective last May at the American Craft Museum in New York, samples of his subtly tinted flax and linen sheets, as rich in texture as Oriental carpets, silenced years of criticism from book art circles that he was making “baby blankets,” not paper. And pieces by other artists—among them Chaim Gross’s 1955 serigraph printed on a Howell scroll and Michael Ponce de Leon’s sculptured spirals—suggested the flexibility of Howell’s papers in others’ hands.

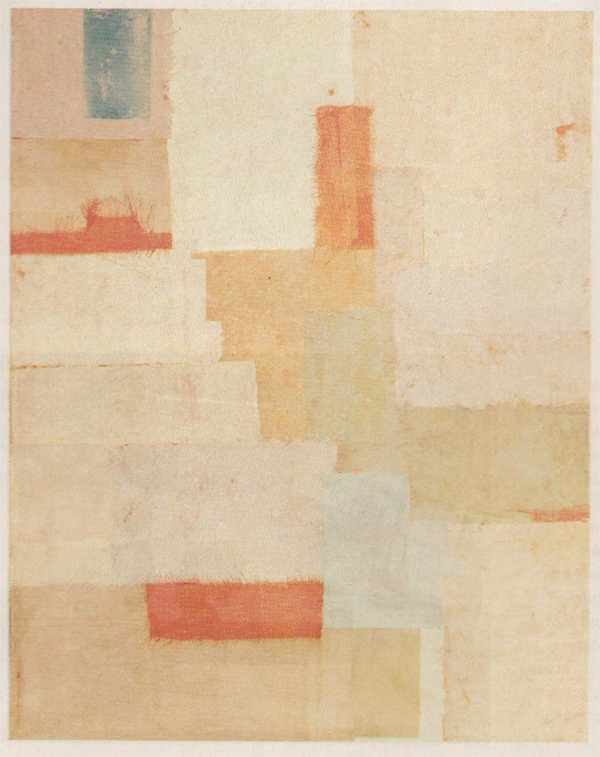

Anne Ryan was one of the first artists to use Howell’s papers; it was a 1951 exhibition of here collages that led Pollack and hist wife, Lee Krasner, to Howell. In Ryan’s work, the textures of the papers are as important as their arrangement. “No. 652”, 1952, 35 x 26.5 inches. Thyssen- Bornemisza collection

Today, Howell is regarded as the dean of handmade-paper makers by many observers (with a nod toward the late Dard Hunter, whose influential 1943 text Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft preserved in print techniques that were being lost with the rise of industrialization). But some papermakers argue that printmaker Laurence Barker has had even more influence on the making of handmade paper today. Barker, a printmaker who studied briefly with Howell in 1962, went on to establish the first paper mill at an American college at Cranbrook in Michigan the following year. His own work, his teaching, and his constant experimentation made Cranbrook and later Barcelona, Spain, where he established his own mill, the Barcelona Paper Workshop, in early 1970, centers from which the new excitement about handmade paper radiated. One of his students, Walter Hamady, established another paper outpost at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where he still teaches.

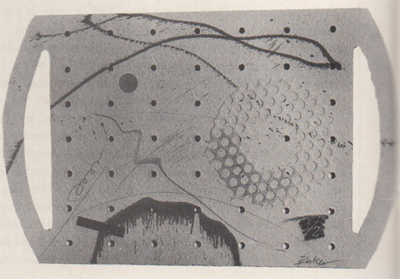

Like Howell, Lawrence Barker has been instrumental in the paper revival both as a teacher and as an artist. Many of today’s most innovative young papermakers, particularly those in the Midwest and on the East Coast, studies with him in Michigan or at his new mill in Spain. In his own work, Barker draws in pencil and ink and embosses the paper surface. “Untitled #6”, 1979, Cotton rag paper, ink and pencil. 16 x 26 inches. Alice Simsar Gallery, Ann Arbor.

By the early 1970s, the number of artists and artisans interested in papermaking—veterans of Howell’s short workshops, students of Barker and Hamady, and the rapidly expanding California papermaking community associated primarily with Garner Tullis’s Institute for Experimental Printmaking in San Francisco—had reached critical mass. A flood of new work, small mills, and collaborations between artists and artisans transformed the medium.

“Papermaking USA, History, Process, Art,” the May 1982 show that inaugurated the American Craft Museum’s gallery in the International Paper Building, offered one measure of the range that papermaking spans today. Sculpture, painting, prints, and exotic constructions in various pulp-generated media coexisted with more traditional paper sheets, and artists like Kenneth Noland (who now has his own paper mill in Vermont) and ceramist Robert Arneson rubbed shoulders with people whose primary medium has been paper. One standout in this latter category was Frederic Amat, a Catalonian-born student of Laurence Barker, whose heavily texturedjuliol rivals the baroque excess of Gaudi’s Church of the Sagrada Familia.

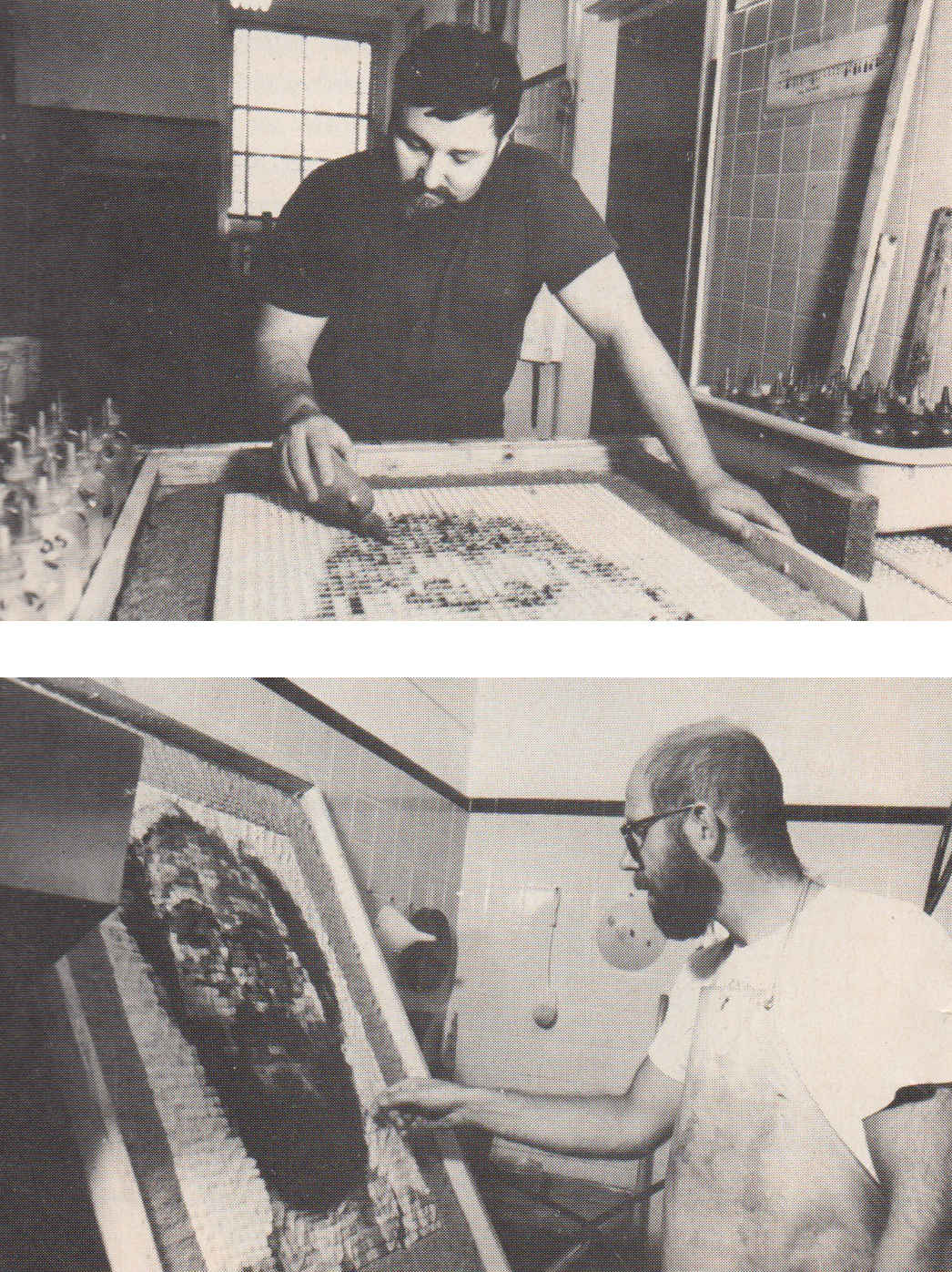

Paul Wong works at a vacuum table at Dieu Donné Press and Paper Mill in New York. Like many university-trained papermakers Wong is both a craftsman and an artist.

The vitality of the best experimental work by lesser-known artists who have devoted their major energy to papermaking was also apparent in “New American Paperworks,” an exhibition that made its first international stop at the Kyoto Museum of Modern Art. Curated by Jane Farmer for the World Print Council, the show surveyed some of the most sophisticated products of twenty papermakers currently working in the United States. Among them are: Zigi Ben-Haim, who constructs his large, obsessively textured paper sculptures in New York; Suzanne Anker, who worked with Garner Tullis in California in the mid-1970s; Charles Hilger, another member of the California papermaking crew and a pioneer in the use of the vacuum table for forming handmade paper; and two artists, Nancy Genn from Berkeley and Steve Sorman from Minneapolis, whose mural-sized pieces have the translucence of the finest Japanese papers.

Traditional Japanese papermaking skills and techniques—which have inspired many contemporary artists and artisans in the West—are, ironically, dying out in Japan, victims of modern technology and the mortality of such elderly practitioners as Living National Treasure Eishiro Abe. Forty-one-year-old Ida Shoichi is a stellar example of contemporary Japanese artistry. His abstract mastery of folded kozo paper, flecked with twigs and tinted with watercolor inks, have the virtuoso touch of a young Ad Reinhardt or a mature Jasper Johns. “Surface Is the Between,” his recent series of handmade, molded paper works, reaches the highest level of harmony and balance between craft and a personal aesthetic. Shoichi’s sophisticated, assured vocabulary of stained squares, triangles, and circles torpedoes the assumption that the West has cornered the contemporary printmaking aesthetic.

A familiar image takes a new form in a 1982 collaboration between (top) Joe Wilfer and (bottom) Chuck Close. “I love the physicality of pushing the pulp,” says Close. It’s like making a pizza.”

Nonetheless, it is true that many of the artists and artisans who attended the 1983 international handmade paper conference in Kyoto were, in fact, Westerners. Perhaps the best known of the American participants was Robert Rauschenberg, whose abiding interest in papermaking is exceptional among mainstream American artists. In 1973, some three decades after Howell’s experience in France, Rauschenberg visited the de Bas mill with Ken Tyler (who was then working for Gemini G.E.L., the printmaking atelier). Working with Marius Peradeau, Howell’s old adviser, Rauschenberg produced a series of multiples, “Pages and Fuses,” on handmade paper.

Rauschenberg’s recent paper pieces, “Seven Characters” — 490 collaged and gold-leafed sheets recently exhibited at Leo Castelli Gallery and at the Museum of Modern Art—represent an even more lavish cultural exchange. Rauschenberg created this mammoth suite in ten, round-the-clock days at the Xuan Paper Mill in Anhui, China; the mill is considered to be the oldest in the world, literally the birthplace of paper. In Seven Characters, collaged images—Chinese department store diagrams of acupuncture and chubby babies, swatches of Chinese bridal bedspreads, hair ribbons, and typical Rauschenberg flotsam and jetsam that lack the resonance of the artist’s earlier work—hover over raised ideograms molded from paper pulp. The elaborate techniques that Rauschenberg invented in situ so impressed workers at the mill that they stamped the seal of Xuan on the lower-right-hand corner of the sheets.

Less exotic than Rauschenberg’s pied-pipering in the People’s Republic but perhaps more aesthetically significant are Chuck Close’s new print editions and unique pieces made in collaboration with veteran pulp-smith Joe Wilfer. Close’s new large portraits, executed in paper pulp in twenty-two shades of gray, break fresh artistic ground. Paper pulp and new techniques seem to have inspired Close not only with new ideas but also with new energy: in the previous fifteen years.