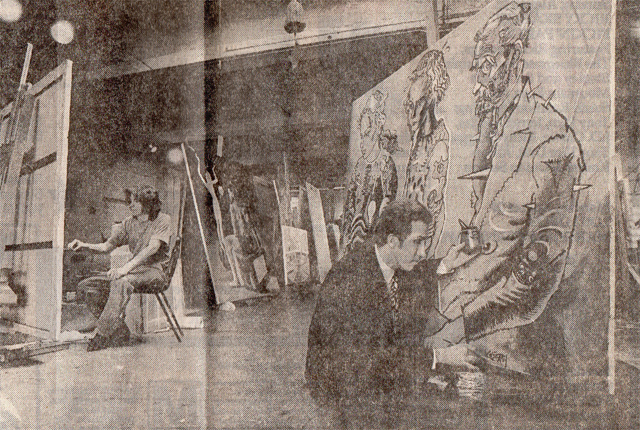

Artist Mark Kostabi kneeling at center with other painters at his studio. photo credit: Cori Wells Braun

Mark Kostabi, king-con of the ’80s art world, doesn’t dye his hair anymore or wear “clown suits” from Charivari. “In the ’80s I was a parody of greed,” admitted the artist as he sipped a root beer in his corporate-style office at Kostabi World, the idea bank and hired-hand painting factory for Kostabi products. “In the ’90s I’m a real person.”

The mounds of publicity have not abated despite his swearing off Andrew Dice Clay bad -boy imitations for the media. Kostabi has been a marked man in Manhattan ever since his art world gay-bashing remarks were published in a Vanity Fair profile in June 1989. “These museum curators, that are for the most part homosexual, have controlled the art world in the ’80s,” Kostabi told Anthony Haden-Guest. “Now they’re all dying of AIDS, and although I think that’s sad, I know it’s for the better.”

“I apologized numerous times in the press,” Kostabi says now. “It was wrong for me to wander into that territory because it is too serious and sensitive. It continues to haunt me.”

Kostabi hired PR superstar Howard J. Rubenstein Associates to repair his image. Rubenstein is also steering Kostabi’s most ambitious plan to date, Trumpian in scope, a $500 million collaborative project for a “vertical art city.” A 2,000-foot tower, the world’s tallest, is envisioned, stabbing the skyline on the Brooklyn side of the East River and covering a 30-acre landscaped site. The building design is by Israeli architect Eli Attia and the San Diego-based ecology-artist duo Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison. “It will be a monument to creativity as opposed to a monument to greed,” said Kostabi, who has already named his fantasy Kostabi World Tower. He would like to find Japanese investors, who recently have begun to take a major interest in his art, to support the project.

But the backlash on the Vanity Fair piece continues. According to Kostabi, Abbeville Press canceled its contract to publish a gigantic artist-financed coffee-table book, now titled “Kostabi – The Early Years,” two months after the controversial article appeared. Kostabi sued the publishing house for $3.7 million in New York State Supreme Court in fall 1989 but dropped the action shortly after.

“We decided that was not the best way to pursue it,” noted John Koegel, Kostabi’s attorney on the lawsuit.

Most of the 5,000 copies of the 524-page tome, printed in Japan and published by Vanity Press at a cost of more than $500,000, are stacked in four-foot-high rows of cardboard boxes at Kostabi World. The enterprise occupies a cavernous three-story building in a seedy West Side neighborhood dominated by old horse carriage stables, cab repair garages and I.M. Pei’s sleek Jacob K. Javits Convention Center.

Just last month, after an item in the Village Voice reminded the owners of Charivari, the ultra-fashionable 57th Street boutique, that their mural-sized Kostabi hanging at street level was the work of a gay-basher, the store returned “To Be Titled” to Kostabi World.

It is currently on view there in the reception/gallery area, along with other Kostabi paintings and sculpture (what the artist refers to as “solid souvenirs”). Figurative, robot-like images, most of them culled from art history books, dominate his witty canvases. The gallery also doubles as a pool hall and a recital hall for the workers, with the hulking oak-finished billiard table and polished grand piano parked there.

Kostabi is a delegator, presiding over his factory like an over-energized corporate CEO. In fact, he’s described his painting style as Neo-Ceo, a clever play on the once-popular East Village art movement called Neo-Geo, as in geometry.

Artist Mark Kostabi, kneeling at right, signing one of his latest works in the studio. photo credit: Cori wells Braun

While Kostabi disappeared to finish a session with a Japanese television crew, work continued in the “think tank,” the second-floor carpeted office where painting ideas are cranked out on illuminated drafting tables by three of Kostabi’s idea people.

Appropriation is the watchword here: snatching images from any number of artist monographs shelved there and turning them into Kostabi-ized cartoons, borrowing freely from Norman Rockwell to van Gogh.

“Internal Revenue,” for example, appropriates van Gogh’s famous “Irises” but with the Kostabi touch of collaged images of hundred-dollar bills clinging to the flowers. “We’re busy doing ideas, and Mark is the art director,” explained idea man Mike Cockrill, who paints his own ideas when he’s not on the time clock at Kostabi World. “It’s kind of like working for Walt Disney.”

“The think tank has a lot of leeway,” commented a newcomer to the tank, Rick Prol, recruited from the painting crew. Prol used to compete with Kostabi for media attention during the brief East Village art boom of the early ’80s, but his star, unlike his ex-rival’s, faded. Prol also served as Jean-Michel Basquiat’s studio assistant during the last turbulent months of that artist’s life; Basquiat died of a heroin overdose at age 27. Prol executed many of the artist’s late works in his own hand.

“We can try stuff here that will never make it upstairs,” Prol explained.

Upstairs is the painting floor, where ideas approved by a Kostabi-appointed committee, of which he is a member, are executed in oil and in a variety of predetermined sizes by any of the 20 painters employed by Kostabi. Most of the men and women are young, tattooed and listening to Walkmans as they paint away, night and day, up to 56 hours per week. The pared-down summertime crew can knock off up to 10 completed oils a week, from idea to the signed and titled painting.

Kostabi envisions a factory of 200 painters producing two paintings each per week, but for the moment his plate is full meeting his $100,000-per-month overhead.

Would 200 painters cranking out 400 Kostabis a week would kill his market? In response, Kostabi unleashed one of his ceo-famous answers: “I don’t think I’ll make a dent in saturating the market. There’s an incredible, vast potential for consumers in the world. In fact, there’s an art shortage so I’m trying to make as many paintings as possible.”

Asked how many paintings he sold last year, the artist said, “There must be over 1,000,” but amended the answer to, “You’d have to ask my bookkeeper. I try not to concentrate on that. My most honest response is, not enough and I haven’t made enough {money}.” Kostabi said he took in $2 million last year and projects $4 million in gross earnings this year.

Approved drawings are first projected directly onto a prepared blank canvas for tracing and then carted upstairs to the painting nursery. Ideas as well as finished paintings can be rejected at any number of “quality control” points along the way.

A big hand-printed sign on the back wall of the painting floor exhorts Mao-style: “The Price of Innovation is Risk. The Prize is Leadership.”

Notices from the Great Expediter are everywhere, including a “Memo to all Painters: Do not take ideas out of the `ideas waiting for approval’ file – no matter how good you think they are … Thanks, Mark.”

Kostabi, his “rhetorician” and painting titler Joachim Neugroschel (a widely published translator) and his curatorial consultant and sometime titler Norman Dubrow were sizing up a canvas, hurtling criticism at the still-wet image. “It’s too gimmicky and cutesy,” growled Dubrow, a recently retired civil engineer and a well-known collector of contemporary drawings.

Dubrow and Kostabi were selecting paintings for a 200-work traveling retrospective of the artist opening in Tokyo at the Mitsukoshi Museum next April. They were choosing from the 400 or so paintings on the premises. “It’s too big a canvas for a very small idea, and that’s the trouble with a lot of the paintings,” snapped Dubrow as another canvas is about to be recycled. Kostabi didn’t protest Dubrow’s verdict; he glumly said, “I agree.”

The artist simply waited with paintbrush and a takeout coffee cup filled with red paint to sign and date each approved painting on the back of the image. Dressed in black jeans, white shirt and a flowered tie, Kostabi demonstrated a flair for signature, choosing the appropriate spot for his mark, about the only physical labor he does during the whole long process.

Kostabi didn’t always delegate or wait around for committee approval. It wasn’t until after his first solo show with the respected Ronald Feldman Gallery in SoHo in 1986 that the urge to increase his production took shape, amplifying what legions of artists have done, from Rembrandt to Warhol: hiring underlings to get the job done.

At first, Kostabi advertised for “skilled, academic, realist painters” at $7 per hour in the Village Voice but in a short time word-of-mouth took over and his painting factory grew, as did his income.

The artist says his factory paintings sell for between $7,000 and $20,000. His highest price at auction was set at Christie’s when “Adele’s First Kiss” (1988) sold for $11,000 in February 1990, the same month he had a solo show at the Govinda Gallery in Georgetown. Kostabi said he’s gone back to painting on his own (mostly at night) and “exploring texturalities,” but as yet cannot explain to his factory painters how to make these new, emphatically expressionist paintings conform to an assembly line. Just as his hourly workers can’t mime this style, Kostabi is equally adrift in painting the images that he markets, along with Kostabi T-shirts and puzzles, internationally.

“I believe in my Kostabi World system 100 percent,” he said. “I also believe in making art on my own without assistants 100 percent. I can paint a classic Kostabi much quicker than anyone here, but there’s no need to.”

Back in the committee action, the bearded Neugroschel shouted a title suggestion above the rock music: “What about `Paradise Lost’?” “You don’t need any downbeat titles,” scolded Dubrow, “and besides no one but you reads Milton.”

“That’s a good painting,” enthused Kostabi, as he moved along the assembly line of easels and pointing to a Jackson Pollock-like canvas shedding some of its paint like tears on a gallery floor. “That’s a Rick Prol execution of a Mike Cockrill idea for a Kostabi painting.”

Many of the canvases that were rejected are recycled, serving as the backside for new attempts. “We created a more interesting kind of object – the collector gets two paintings for the price of one,” said Kostabi. “It’s unique and it makes it difficult to forge. It also makes the painting more archival since there’s paint on both sides, sealing the canvas.”

At his mention of forgery, one of his assistants snickered. Asked if he is concerned about forgery, Kostabi said: “Any great artist eventually gets forged and I’m anticipating the future. I’m sure I’ll be no exception so I’m deliberately making it more difficult.” Asked if it had already happened, Kostabi shrugged and said, “Let’s put it this way: Something happened. That’s the sound bite.” Pressed to elaborate, Kostabi only noted, “I value justice above publicity, and I don’t want to say anything that will interfere with the DA’s investigation.”

“An assistant DA assigned to our Fraud Division and also another assistant assigned to our Special Prosecution Division are conducting an investigation of Kostabi World for possible fraud perpetrated there,” acknowledged Colleen Roche, deputy director for public information at the New York County District Attorney’s Office. Roche said the district attorney would go to the grand jury if the evidence warranted it.

According to one source at Kostabi World, the suspected fraud was uncovered by Kostabi’s brother Indrek after a Japanese gallery returned a small painting to Kostabi World, complaining that a duplicate already existed.

One of the suspect paintings rests on the shelf of a steel file case at Kostabi World, hard to separate from other small canvases stacked there.

The concept of a “forged” Kostabi is slippery to grasp, given the artist’s techniques in appropriation and mass production that often make his paintings look like enlarged post-modern greeting cards. In his line immortalized in “The Early Years” and uttered during a “To Tell the Truth” quiz show appearance: “Look at them … fake Kostabis with real Kostabi signatures.”