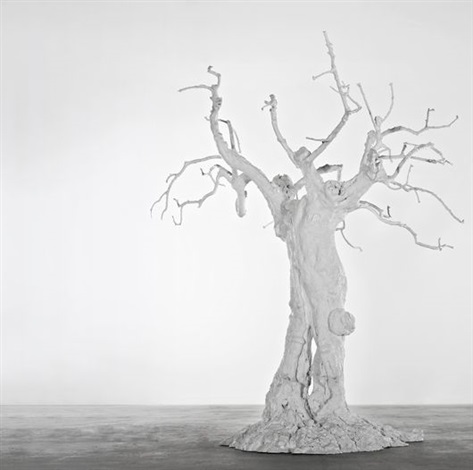

Ugo Rondinone, Air/ gets/ into/ everything/ even/ nothing, 2006, cast aluminium, white enamel, 381 x 381 x 335 cm. (150 x 150 x 131.9 in.)

In the spring Phillips de Pury & Company looked confident after a successful New York season.

It had snagged the consignment of the Internet entrepreneur Halsey Minor’s contemporary-art collection, which realized $45.6 million, and was anticipating the November opening of its high-profile space on East 57th Street. There was buzz as well about the sale that will inaugurate that venue, Carte Blanche, curated by the New York art adviser Philippe Segalot.

The glow was short-lived, however, and by the summer the house was trying to put a good face on its June 29 contemporary-art auction in London, which sold just 53 percent by lot, netting £3,963,450 ($6 million)—nowhere near even the low estimate of £66 million ($9 million). It all served to reinforce the view that Phillips, long in the shadow of Sotheby’s and Christie’s, is struggling to find a viable strategy in a very competitive market and less than robust economy. One particularly interested observer of that struggle is probably the Mercury Group, the Russian retail luxury company that acquired a majority share in the firm in October 2008. How long, one has to ask, will Mercury continue to pump money into Phillips?

In large measure, the house’s difficulties can be laid to the big stake it has in promoting art mostly in the same price range as the material in the Christie’s and Sotheby’s day sales. “The secondary market for contemporary art is weak and that’s what they’re in,” says a New York art adviser requesting anonymity, who adds that consignors parting with “anything of any value” are more likely to do business with Sotheby’s or Christie’s.

“People feel they can go to Phillips and buy things at a 30 percent discount—it will be cheaper because there’s not a lot of competition,” says the New York dealer and art trader Alberto Mugrabi. “The only smart thing they’ve done is to hire Philippe [Segalot] to do this one sale.”

Although Phillips sold Ugo Rondinone’s tree air/gets/into/everything/even/ nothing, 2006, for a record £361,250 ($544,422) in its June auction, works by such trendy artists as Urs Fischer and Matthew Day Jackson failed to entice bidders. “The Rondinone was a great lot for Phillips,” says the New York adviser. “But it’s hard to capture [works of that quality] when Christie’s and Sotheby’s are dying for things to fill their auctions. Maybe there’s not enough to go around in lean times.”

Phillips chairman and auctioneer Simon de Pury brushes off criticism of the London results and denies that the house’s market share is shrinking. “We were at the end of the summer season, and the good works in the sale did well,” he says, noting that “we’re 127 percent ahead of the first six months of last year,” and that consignments for the rest of 2010 “are back in terms of volume to 2007.”

De Pury also points to enthusiastic reactions to the house’s expansion uptown from its base on West 15th Street and to the Carte Blanche sale, the first of a planned annual series of auctions to be organized by art world luminaries. He touts as well the success of Phillips’s themed sales, a strategy the firm has adopted to parry the strength of its larger rivals. In addition to holding regular sessions in London and New York in major categories of design and contemporary art, it has launched a sched-ule of sales under such catchall rubrics as BRIC, Music, Latin America, and New York. “The continuation of the themed sales,” says de Pury, who initiated the campaign two years ago, “has greatly contributed to our very good first half of the year.”

The strategy does have a downside. “I don’t know anymore where to look for material at Phillips, and I don’t know when to look for it,” says the New York dealer Leon Benrimon, who has both consigned and bought works at Phillips. “What the market needs right now is to bring great material at the right time and not to bring mediocre material sporadically. That’s what’s going to win, and I don’t really see Phillips doing that.”

The full schedule is also exhausting for Phillips’s specialists, who have had to organize several sales in untested categories on top of the usual auction calendar. “They don’t have enough staff to cope with the volume that they’re trying to create with their themed sales,” says one former staffer.

What Mercury thinks of all this and how it affects the health of its investment is a matter of speculation, since principles Leonid Friedland and Leonid Strunin do not

speak to the media. De Pury, however, is completely sanguine about the two Leonids’ attitude. “I assure you,” he asserts, “that they are happy campers and are feeling very positive about the way things are going.”