Grahm Southern and Harry Blain

With Auctions and art fairs hogging so much of the limelight these days, galleries are moving in on museum turf to draw much-needed attention, During the London auctions of contemporary and Impressionist and Modern art in February, several private galleries in Mayfair touted their own mini blockbusters: highprofile, not-for-sale loan exhibitions of work by modern and contemporary masters.The accompanying catalogues will endure as important scholarly contributions on key twnetith century artists. The real aim, however,was to attract interest, and not just thatof wealthy buyers. The lasting payoff for the galleries, in terms of relationships solidified andnetworks built, will be difficult for those outside to gauge.

Why are museum-quality nonselling shows all the rage at london’s for-profit galleries?

“First of all, it’s very prestigious. It’s a way of saying, ‘We’re so successful,we don’t need to sell anything, — observes Wendy Goldsmith, a London based private art adviser “The other reason is that technically nothing is for sale, butdon’tthinkthey’re not approached for the very good things. It’s also a clever wayto get close to an artist or artist’s foundation or estate. Not only will you be approached forworks in the show, evenifthey’re not for sale, but if someone wants to sellsomething privately and not through an auction house, where are they going toturn? It’s very clever for a multitude of reasons, but you need very deep pockets to do it.”

“From a commercial standpoint, it’s a long-term view,” notes Nicholas Maclean in the sleekback room of the Eykyn Maclean gallery on St. George Street.The space wasinaugurated this season with “Cy Twombly Works from the Sonnabend Collection,” featuring an elegant display of 11 works, including the artist’s 1956 breakout painting, Untitled (NewYork City). ” As a private dealer, you have a certain number of clients and that becomes your world, yet there are many othersout there who can find out what you are doing.” His partner, Christopher Eykyn, adds, “It gives us exposure that otherwise wewouldn’t behaving.”

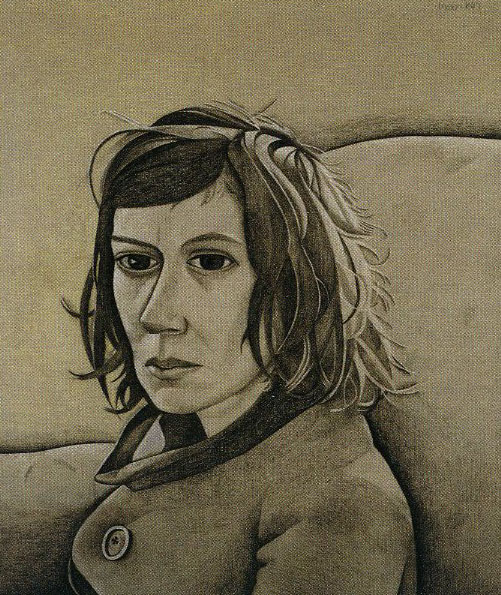

Left La Voisme (The Neighbour), 1947, is among Lucian Freud’s works on paper displayed at Blain/Southern’s new Hill Street venue in London. Co-organized with the artist’s New York dealer,

Acquavella Galleries, the exhibition was originally planned to tour museums.

A week after the Twombly opening,the Ordovas gallery on nearby Savile Row debuted “Julio Gonzalez: First Master of the Torch.” It is the first exhibition in London devoted to the Spanish sculptor sincea Whitechapel Art Gallery exhibition in 1990. Including not-for-sale works by artists influenced by Gonzalez, such as Anthony Caro, Eduardo Chillida, Picasso, and David Smith, the show came on the heels of Ordovas’s inaugural show last October, “Irrational Marks: Bacon and Rembrandt.” Alsopegged as noncommercial, that display included loanslike Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait with Beret, circa 1659, from the Musee Granetin Aix-en Provence. For this outing, Ordovas ran into a big road block when a temporary export license for four of the eight Gonzalez works fromthe Institute Valencianode Arte Modern were delayed due to a bureaucratic snafu in Spain, and the exhibition opened without some of its star pieces.

“My aim is to show a museum-quality programof 20th -century art,” says Pilar Ordovas, a former head of postwar and contemporary art at Christie’s in London and, more briefly, a veteran of Gagosian Gallery. “Withmy current exhibition, all the loansexceptoneare institutionaland there is nothing for sale: This is a noncommercial exhibition. My commercial activity involves advising clients and helping them navigate the market in a one-to-one, discreet, and personal way.”

Perhaps themost stunning oftheserecent private endeavors is “Lucian Freud Drawings,”which inaugurated Blain/Southern’s Hill Street town house location. With more than 110 works spanning Freud’s career, it is the largest selection of the artist’s drawings ever assembled. It opened just days after the highly anticipated Lucian Freud retrospective at London’s National Portrait Gallery and as other Freud works on paper, including important early examples from the 1940s, were being offered at both Christie’s and Sotheby’s. And Blain / Southern put on an ancillary show of related material, “Lucian Freud Drawings Archive,” at its nearby Dering Street location.

Christopher Eykyn and Nicholas Maclean

While Eykyn Maclean and Ordovas are strictly secondary-market salons for Impressionist, modern, and contemporary works, Blain/Southern is involved in representing living artists, and some might think this is a selling show, but the exhibition was originally conceived for an institution, “There was no expectation it would come to us, ever,” says Graham Southern. “The initial ideawas a Dutch museum and

maybe a Swiss museum and possibly bringing it back to London. It was all quite fluid. It eventually hit the wall.” Adds partner Harry Blain, “It was actually Lucian’s suggestion to do it at our gallery. The only disappointing thing was that he wasn’t around to see it through to fruition.”

Though Freud didn’t live to see the exhibition, whose works were selected by Freud expert and friend William Feaver, the artist approved of the ventureand helped ensure that almost 100 percent of the loan requests were met. Freud even allowed about 16 drawings to be removed from his 1940s sketchbooks and included in the exhibition.”This was very much a show driven through conversations and friendship with Lucian,” says Southern. It therefore seems especially appropriate “to show the private and personal side in a slightly more residential situation.” To help preserve theshow’s intimacy, the dealers control entrance through advance ticketing.

Both the Twombly and the Freud shows are traveling to New York in the spring, Twombly heading to Eykyn Maclean’s outpost on East 67th Street this month, and the Freud in May to Acquavella Galleries, the late artist’s dealer, which is credited with coorganizing the exhibition. Of course, New York has been home to high-profile loan shows in galleries before, most notably Gagosian’s stagings of work by Piero Manzoni, Claude Monet, and Picasso. And last year Acquavella mounted a major Georges Braque exhibition accompanied by a scholarly catalogue.

Pilar Ordovas

At the moment, however, conditions in London are ideal for these highcaliber showcases,especially given the city’s popularity with Russians and others who want to be inconspicuous in spending what U.K. tax authorities categorize as nondomiciled wealth. “The geographical position of London has given the city a greater advantage, and obviously, it’s not just the home of European collectors,” Ordovas observes. “It has attracted Asians and other communities and made it much easier in every wayto access a lot of people who don’t intend to go to New York or do not have second homes in America. I think it’s mainly why we’re seeing American galleries establishing themselves in London for the first time.”

Ordovas is referring to Pace Gallery, which opened an office last year on Lexington Street in Soho while shopping for a bigger location in Mayfair, and also to the David Zwirner gallery. That powerhouse has snagged a major space in Mayfair, though it has yet to make an official announcement of opening its first satellite outside New York. “Mayfair is nice and central,” says Blain, referring to the gallery enclave. “People stay in this area when they’re coming to London—at least a lot of the collectors and curators and museum directors do. It’s all about making it as easy as possible for people to see exhibitions and to engage with theart while in London.”