Keith Haring and LA2. Photo: Tseng Kwong Chi

“Don’t push me ’cause I’m close to the edge,

I’m just trying not to lose my head.

It’s like a jungle

Sometimes it makes me wonder how I keep from going under.”

The Furious Five were hot on the cobblestoned SoHo art circuit this fall. In just a fiscal quarter’s time, the street-smart waifs who scrawled, pasted, stenciled and splattered their graffiti on outside walls can now be viewed inside, strutting in front of their properly framed and price-tagged work. Witness the pubescent imagery of Avant (five-member graffiti group active in New York since the fall) on exhibit this month at the Gabrielle Bryers Gallery on Greene Street and Futura 2000’s spray-painted canvases at the Fun Gallery on East 10th Street.

Graffiti or the tired tag known as “radical chic” has scurried up from the subway knocking over slide-carrying M.F.A.’s on the make (recent figures from New York City’s Housing Department reckons there are 93,000 artists living in the metropolitan area). Keith Haring— an Avedon-ish street urchin if there ever was one—has replaced the battered Julian Schnabel as the ever-fickle art world’s star of the moment. A film crew from Dan Rather’s CBS Nightly News shot his opening in October at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery (Shafrazi must be partial to graffiti—he holds the dubious distinction of vandalizing Picasso’s Guernica in 1974 with spray paint before it was repatriated from MOMA to Spain). Black on white buttons with Haring’s crawling Casper-the-friendly-ghost-image adorn well-tailored lapels on 57th Street and scruffier ones on Avenue B.

That scenario tints one segment of the New York art market. It is a twilight zone miles away from Christie, Manson & Woods International on Park Avenue where one of their November auctions of contemporary art set a number of records for both living and dead American artists. David Smith’s polished steel Two Doors (1964) sold for $572,000, the highest price ever paid for a post World War II American sculpture. Robert Rauschenberg’s combine Studio Painting (1960-61)—a six-foot square diptych with a stuffed canvas bag and impeccable provenance—snared $385,000. On the lower end of the eyebrow-raising prices was an acrylic on paper 60″x42″ drawing by David Salle (from the late Betty Parsons collection) which sold for $4,400, easily hurdling the estimated range of $53-4,000.

While Christie’s—usually pegged as the Avis of the auction houses to big daddy Sotheby’s—outpaced their rival for the first time in 30 years with record sales of $137,679,150 for the first half of the 1982 season, takeover rumors at SPB have caused the troubled giant to quake in its claw-footed Chippendale chair. World-wide sales at Sotheby’s plummeted $85,000,000 or forty percent from their 1981 September to December performance.

On Christmas day, an item in the New York Times reported the first fires of internecine warfare between the company’s newest and biggest shareholder, GFI/Knoll International (a subsidiary of General Felt Industries, Saddle Brook, New Jersey, the world’s largest producers of carpeting and padding) and Graham Llewellyn, Sotheby’s chairman. The blue-blooded London director-ate (holding only fourteen percent of the stock) was harshly criticized by GFI for closing SPB’s Madison Avenue flagship (consolidating further east on York Avenue), and selling their outpost in Los Angeles. Traded over the counter in New York, Sotheby’s stock is zooming upward again due to takeover fever.

Whether there will be GFI-turfed showrooms in SPB’s future is anybody’s guess, but the myth-popping plight of SPB is not the only trouble spot on the art world map.

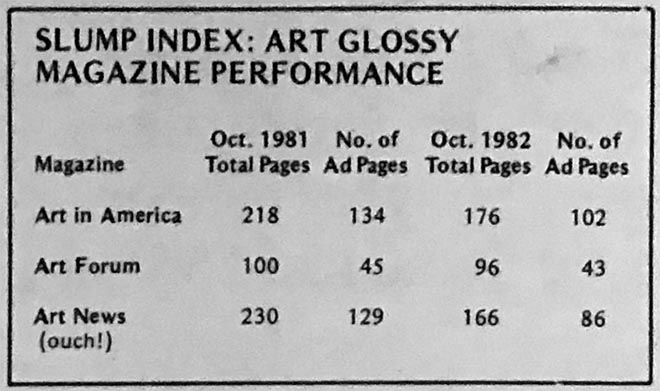

Art publications are feeling the economic slump as well. (See table.) Counting up ad pages in three of the monthly art magazines and comparing them to 1981 figures bear out Art in America publisher Paul Shanley’s analysis that more European dealers’ advertising pages had to be solicited to offset the domestic slide in buying space. The October 1981 issue of Art in America (with Mondrian’s striped New York City on the cover) ran 218 pages, 134 of them ads. The same month in 1982 (Ed Paschke’s Rufus was the cover boy) ran a slim 176 pages of which just 102 pages were ads. A special six-page, lavender-typeface-on-salmon-colored-stock International Exhibition Directory cushioned the blow. It is rumored that the long-standing back cover holder of Art in America, Flow Ace Gallery in Venice, California, is $35,000 behind in ad payment.

Art publications are feeling the economic slump as well. (See table.) Counting up ad pages in three of the monthly art magazines and comparing them to 1981 figures bear out Art in America publisher Paul Shanley’s analysis that more European dealers’ advertising pages had to be solicited to offset the domestic slide in buying space. The October 1981 issue of Art in America (with Mondrian’s striped New York City on the cover) ran 218 pages, 134 of them ads. The same month in 1982 (Ed Paschke’s Rufus was the cover boy) ran a slim 176 pages of which just 102 pages were ads. A special six-page, lavender-typeface-on-salmon-colored-stock International Exhibition Directory cushioned the blow. It is rumored that the long-standing back cover holder of Art in America, Flow Ace Gallery in Venice, California, is $35,000 behind in ad payment.

Artforum is a shade under their 1981 ad performance for the month of October (45 ad pages out of 100 for 1981 versus 43 out of 96 for 1982).

Hardest hit of the art glossies was the one-time king of the road, ARTnews. Their October 1981 issue (Treasures of the Vatican) ran 230 pages, 129 of them ads. The same month in 1982 (featuring Keith Haring’s Day-glo Bowery Mural, with his right hand man, L.A. 2, crouching in front of it) ran an emaciated 166 pages, a fraction under 86 of them ads.

Ad declines reflect the unstable gallery situation. It is old hat by now that the photography market, manipulated to ridiculous heights in the eighties, has crashed into a large, street-level dumpster. After a flurry of expansion on 57th Street and Los Angeles, Light Gallery shut down this fall, bringing out the space available sign at 724 Fifth Avenue, the high-rent home of Robert Miller, Grace Borgenicht, and the newest tenant of all, Zabriskie Gallery.

Robert Stefanotti closed his doors at 30 West 57th Street, his second failure on that street, only to reappear downtown as director of the two-tiered Bonlow Gallery (the Swedish enterprise of Jeanette Bonnier and Jan Eric Lowenadler). Stefanotti has a curious track record of piling up astronomical gallery debts, disappearing and bouncing back under new sponsorship.

On the landmark corner of West Broadway and Spring Street, Elise Meyer Gallery bit the dust and now high-tech dustpans can be purchased from the new proprietors, Ad Hoc Softwares. A few blocks to the East, Betty Cunningham Gallery, a post-modern fixture above Fanelli’s bar on Prince and Mercer, closed after a dozen years.

Art dealer Dick Lerner’s death at 53 in September leaves a diverse stable of artists like Howardena Pindell, Harmony Hammond, Benny Andrews (crown prince of the NEA), Joan Semmel and Rudolph Baranik without New York representation. (Lerner-Heller’s space at 956 Madison is now leased by Thomas G. Schwenke, American Antiques.)

But the biggest shock to the New York cognoscenti is the closing of Roger Litz at 153 Mercer Street, which opened only twelve months ago with a mixed grill of mostly young and even unknown artists. Despite his notorious row with the enormous heavyweight (6’4″, 360 lbs.) painter, Richard Mock (now represented at Brooke Alexander) and a screaming tantrum thrown inside the space by Artforum’s Rilke, Rene Ricard, Litz was a sorely needed promoter of new artists. Without much adieu, the gallery abruptly called it quits in mid-December, with John Ford’s first one-person show in New York taking the final curtain.

Artist David Hatchett was on deck for a January show at Litz, now, of course, cancelled by the gallery’s demise. He contemplated his overflowing studio of jilted sculptures and punk-fauve canvases and surprised this writer with: “I feel real good about it. I would have been worse off if the show opened and then not stay in business. The work would be tainted.”

“Basically everyone was taking a chance showing with them,” Hatchett continued. “I want these pieces to be seen in a gallery that’s going to work. be more select next time. I don’t need another exposure show. I need a successful show. This is a time when things aren’t selling unless you’re hooked up to a super-hype. So you might as well be independent and in the ‘visible under-ground’.”

“I felt Litz closed,” Hatchett concluded, “because they couldn’t get the right people down there. I feel badly for them (the plural refers to Litz’s silent partner/ backer, Elliot Leonard). I hope Roger will continue to deal privately.”

What is the significance–if any—of a small gallery closing on the eastern edge of SoHo while a neighbor up the block at 169 (Metro Pictures) sells out images of the woman with a thousand faces, Cindy Sherman? More perplexing, why close when the six-year old New Museum is moving to permanent quarters across the street (quadrupling their exhibition space) at the land-mark, 12-story Astor Building at 583 Broadway. The new owners of 583 H.Q.Z. Enterprises Inc., presented the museum with an extraordinary present: a two-and a half floor condominium.

“I was showing artists no one had seen before,” Litz complains. “That’s what buried me, My gallery obituary should read: Roger Litz: 1982-1982, It was a question of economics. Even if you cut down on expenses you still need $6,000 a month. My costs for one year were $110,000, Even if I pared it down in 1983 it would have cost $120,000. You can’t expect to sell art that doesn’t have a reputation. You need a support system, I came here without one from This was a business venture, an unrealistic one.”

“There is an art world Mafia operating here,” Litz said, “which I was approached by. They’ll funnel artists to you if you give them a piece. These are the writers, the critics … If you want to get the gallery going faster, you’ll get coverage, you’ll get collectors, you’ll get the right people saying, ‘Buy!’ Whether this Mafia gets a dollar cut I never got that far. I didn’t want someone telling me who I should show . . .”

“No one has money,” grumbled Litz, “except the collectors. When I go back—after the economy picks up—I’ll go with someone else’s money. A dealer like Robert Miller can push a new artist like Greg Amenoff up real fast. He can sell out a first one-man show with paintings at $8,500. I couldn’t give mine away. I gave it a good shot. But no new art is being sold. Only the blue chip. This is a city of power,” Litz crescendoed, “it’s a fabulous and miserable place.”

Phyllis Kind, eight-year veteran of SoHo (16-year veteran of Chicago), and a dialectically agile raconteur shouted in the direction of the discreetly placed tape recorder: “I can’t join the moans and groans. Carol Celentano (PK’s number one New York assistant) just informed me that we’ve done twice as much business this fall as we’ve ever done before. There are people out there—human being types—who are crazy about art.”

“I see collectors,” Phyllis continued, “as being the single most important category of people in the art world today. They’re hardly ever given the credit for what they [do] , those key, key people who can come in and buy that last difficult piece from an otherwise sold out show. Every time you raise a price you shrink the number of people who are able to buy something. It eliminates a certain kind of person whom I like from the race. One might run through too quickly the people who have $25,000 to spend easily.”

It is becoming harder to separate red-blooded word of mouth tattling (the kind that peppers Marsha Fogel’s $150-a-year newsletter, Contemporary Art Observer) from plain old dirty tricks. For at least a year nasty tales of Holly Solomon’s nervous breakdowns and demise have been consistently exaggerated. So have the market obituaries for her stable of “pattern and decoration” artists, especially the stories about Robert Kushner’s wholesale dumping on the auction circuit.

“Robert Kushner is only 31,” Holly Solomon confinded in a stage door whisper. “His October show sold out. I’ve sold everything he’s done this year. There are maybe two drawings of his in the gallery.” Leaning for-ward from the hand-painted club chair of Kim MacConnel’s (Holly calls it “Zurich’s Dentists’ Best”), she continued, “The rumors got so bad over the summer of my closing that I put a sign in the window announcing that Nicholas Africano was opening in September. If I found out who started them I’d sue the hell out of them.”

Lighting another cigarette between paragraphs, Holly (her husband Horace was working out on an ice-blue Selectric across the room) said, “I’ve never known things to just roll off walls. When we opened the gallery in 1975 the art world was in abysmal shape. It’s a tougher and more competitive market today. When people come to see me I assume they’ve been to Leo’s, Paula’s, Anina’s, Tony’s and Mary’s. They don’t buy from ignorance. The hottest moment was 1980. People had money then.

Unfortunately, collectors are very rare. I’m talking about real, hard-core collecting. I don’t ordinarily sell to people who just want an object over the couch. They don’t buy from me. But that’s the kind of market that’s having the severest problems right now.”

Glancing at her man-sized Mickey Mouse watch, Mrs. Solomon struck dumb her visitor with, “I want to leave SoHo and go uptown in a matter of time.” (Holly and Horace estimate it would cost $600,000 in today’s dollars to open a new, first-class operation uptown and about half of that amount downtown. Both prices include rental and enough capital to stay afloat for a couple of seasons.) “SoHo has become a tourist trap. It’s a zoo down here now. Ivan Karp of O.K. Harris Gallery counted 6,000 people during one Saturday a couple of weeks ago. The busloads come in. The landlords will drive the galleries out. But people who want to look at art can’t do it on a Saturday. Their [alluding to Bruce Springsteen’s Jersey Bridge & Tunnel set] idea of culture is going to Dean and Deluca and Turpan Sanders (where you can buy chrome-plated garbage cans) and maybe lunch at the Spring Street Bar. It is bourgeois as hell.”

The unsettling picture of an impatient collector racing blindly through the gallery (ignoring what’s hang-ing up front) to the back room and queueing up for a Salle, Haring or Borofsky is not something out of a comic book. The contemporary art market is alive, snobby and stone deaf to a bumper crop of unproven artists (even to the cry of the wild, “I am figurative now.”). It is doubtful that providence will change the picture.