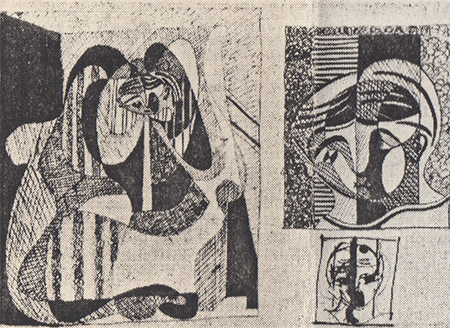

m a page of ink drawings in one of Picasso’s sketchbooks

NEW YORK— During his life-time, Pablo Picasso filled 175 sketchbooks, recording in meticulous detail a vast encyclopedia of images and ideas—everything from the first sketches for his 1907 masterpiece “Les Demoi selles d’Avignon” to the wildly erotic colored chalk drawings “Variation on Manet’s Dejeuner sur l’Herbe” from 1962.

With today’s opening of “Je Suis le Cahier: The Sketchbooks of Picasso,” the Pace Gallery here has managed an international art coup with an exhibit of about 300 images culled from 45 sketchbooks belonging to the heirs of the great Spanish artist.

The exhibition, which runs through Aug. 2, spans 65 years, from 1900, when the 19-year-old Picasso left Barcelona for his first Paris visit, to 1965, when he reigned from his villa, La Califor-nie, as the world’s greatest and richest artist.

And last night his heirs gath-ered at the trendy Area club to celebrate the opening and the book that accompanies it. Picasso’s sketchbooks range in size and paper quality from a 1922 21/2-inch-by-3-inch pad with a stubby pencil still in its holder, which the artist carried to bull-fights or the zoo, to a large spiral-bound book from 1964 highlighted by a double-page portrait of a bearded artist at his easel painting a reclin-ing nude. The artist in a red-checked shirt wields his brush with unmistakable elan.

Some of the pages have slipped out of their bindings, or in some cases the spirals have unwound so that some of his dramatic series can be seen stretched out in a line of six images, from cavorting fat satyrs to elaborately armored Spanish knights.

Until 1965 Picasso kept the notebooks closeted, occasionally tearing out a sketch for a friend. That policy changed as he got older and more protective of his paintings. Instead of giving his Paris dealer, D.H. Kahn-welter, a work on canvas, Picasso would ration sheets from the constantly evolving sketchbooks.

Earlier this week, Marc Glimcher, son of Pace owner Arnold Glimcher, donned a pair of white cotton mesh gloves to gingerly open one diary-size book for a pre-view of the exhibition.

The elegantly bound red silk notebook, chronologically numbered 66, documents Picasso’s 21/2-month summer 1918 honeymoon in Biarritz, France, with Olga Koklova, a soloist with Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe.

The thick white pages unfold with multiple views of the seaside resort observed through high French windows. Exquisite watercolors, some that have not seen the light of day in 70 years, look more Ike Matisse’s signature than the usually tempestuous hand of Picasso.

His continuous experimentation with the flat shapes of synthetic cubism is evident with the ‘beautiful Olga reduced in pencil studies and watercolors to a house-of-cards arrangement of leaning rectangles.

Detail from a pencil drawing in a Picasso sketchbook on view at the Pace Gallery, New York.

During the course of the exhibition, sketchbook pages will be turned over to afford viewers more than a single-page glimpse of the books. In conjunction with the exhibition, a $90 red-slipcased coffeetable volume with precise reproductions of six entire sketchbooks and accompanying essays will be offered in a limited edition of 3,000. A numbered lithograph, printed by Pace with the permission of the Picasso heirs, will be in-cluded in these copies. In September, Atlantic Monthly Press will publish a $60 hard-cover trade version of the book that is virtually identical, minus the slipcase and the lithograph.

And in September, the exhibition will begin a 21-year, 15-city tour (in the United States and Europe) at the Royal Academy in London, sponsored by American Express. A spokesman for American Express said that negotiations are under way to bring it to Washington but that nothing is finalized. Sources indicate it would be at the National Gallery, but a spokesman there said it was not on any printed schedule. The Pace show will be the only place where pages from the sketchbooks will be shown on both sides.

When Picasso died in 1973 at age 92, he left no will and his array of chateaux and about 45,000 uncatalo-gued works of art were left to be pawed over by a small army of lawyers, art experts, government officials and the offspring of his love affairs. The estate was conser-vatively valued in the 1970s at $260 million.

When the dust settled, the French government, in lieu of estate taxes, took 3,488 works and created a Picasso museum in Paris. His widow, Jacqueline, received the equivalent of $52 million in artwork, two grandchil-dren got $35 million apiece, and each of his three ille-gitimate children—establishing a precedent in French estate law—received $18 million worth of art.

A number of discoveries published in the Pace-Atlantic Monthly Press volume shed light on how Picasso translated his love life onto canvas. Gert Schiff, a pro-fessor at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, examined notebooks from 1962 and noted that a sketch for a piazza filled with struggling women and muscular Romans (after Poussin’s “Rape of the Sabine Women”) contained a drawing of a bicycle with a woman falling from it, totally out of context with the rest of the sketches.

The bicycle, says Schiff, represents the end of Picasso’s affair with photographer Dora Marr and the begin-ning of a relationship with Francoise Gilot in 1946.

Marc, distraught with the breakup, staged a bicycle accident on the banks of the Seine to embarrass Picasso.

The sketchbooks also demonstrate the artist’s long memory and his way of mixing personal history with art history. In his treatment of Manet’s serene masterpiece “Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe,” Picasso entered the picture and turned the picnic into a bawdy bacchanal.

None of the sketchbooks is for sale. The heirs to Picasso’s vast estate, from Francoise Gilot (now married to Dr. Jonas Salk) to her daughter, Paloma Picasso, all cooperated with Pace and will share in the royalties of the publication.

The logo for the show, as well as the cover of both versions of the book, mimes Picasso’s notebook from 1906, when he was steeped in his Rose Period of somber harlequins, like the “Family of Saltimbanques” on permanent display at the National Gallery of Art (Sketchbook 35 includes calculations for the dimensions of the painting).

The literal translation of Picasso’s painted cover reads, “I am the notebook belonging to Mr. Picasso, painter.”

In his preface to the book, Arnold Glimcher quotes from one notebook: “. . . I picked up my sketchbooks daily, saying to myself: What will I learn of myself that I didn’t know? And when it isn’t me anymore who is talking but the drawings I made, and when they escape and mock me, then I know I’ve achieved my goal.”