John Rewald, shown above at his home in Minerbes, made end-less excursions into the countryside around Aix to document the motifs so dear to Cezanne.

With the publication later this year of The Paintings of Paul Cézanne. A Catalogue Raisonne by John Rewald (1912-1994), the scholarly affair between artist and an historian comes full circle.

Born in Berlin, Rewald studied at the Sorbonne, where he wrote his trailblazing dissertation on Cezanne. It would serve as the basis for his Mitchell Prize-winning biography entitled simply Cezanne. By the end of his lifetime, Rewald had con-tributed as much to the understanding of the elusive artist as did Ambroise Vollard, the dealer who championed the “hermit from Aix” to connoisseurs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

When the 1986 edition of Cezanne was published. London art critic and painter John Golding wrote, “Rewald has identified with the artist and caught him whole in a way that no one else has.” So much so that the upcoming “Cezanne” exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (May 30 to August 18) was timed in part to allow the Rewald team to finish the herculean task of documenting, dating and authenticating Cezanne’s 954 paintings for posterity. The resulting catalogue raisonne is the first update since Lionelli Venturi’s land-mark 1936 publication, which was sponsored and published by the famed Paris art dealer, Paul Rosenberg. After Venturi’s death in 1960. the family turned over the scholar’s archives to Rewald, who be-came the keeper of the Cezanne flame.

This two-volume work, published by Harry N. Abrams, was completed with the collaboration of art scholars Walter Feilchenfeldt and Jayne Warman after the ailing Rewald blessed their participation. “Mr. Rewald had a phenomenal visual memory,” recalled Warman, who began working with Re-wald on the Cezanne project in 1979. “Someone once called about a painting (Rewald was the esteemed authenticator for market-bound Cezannes) and he said. ‘Oh, I saw that painting 35 years ago in a Paris studio…there’s a little green fine in the upper-left corner. isn’t there?’ People were always blown away by his incredible memory.

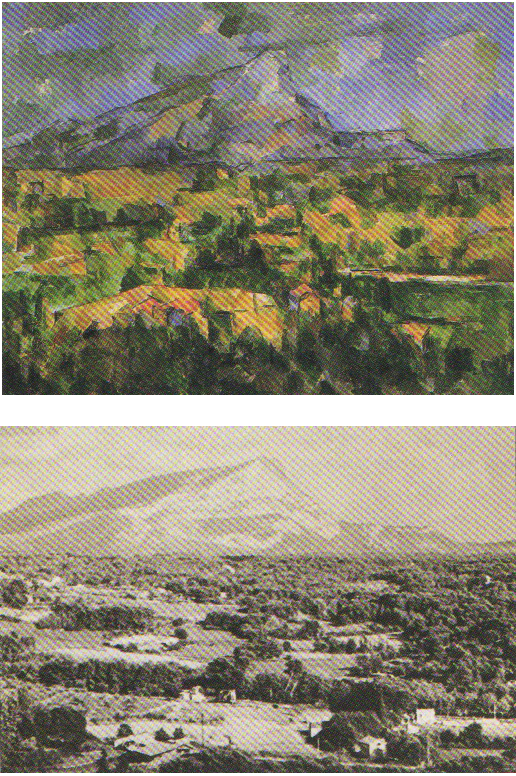

Pictured above are Cizanne’s ‘Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from Les Lauves” (1902-04) and Rewald’s photograph

It was Warman who transferred Rewald’s vast Cezanne archives to a computerized data base and word-processing program. The resulting catalogue raisonne has 12.000 bibliographic references, all of them cross-referenced, as well as more than 5.000 entries on the owners of the paintings. As for Rewald, he was an avowed computerphobe. “He was a two-fingered typist right up to the end,” Warman remembers with awe, adding that Rewald worked on the same manual typewriter for some 40 years and eventually had to have another one custom-made with German and French characters since he wrote (beautifully) in three languages.

Originally a budding scholar of medieval architecture, Rewald made the study of French Impressionism and particularly Cezanne his life work and consuming passion after a chance trip to Provence in 1933. “It radically affected the direction of my work,” wrote Rewald in an unpublished biographic sketch on deposit at The Museum of Modern Art. It was in Aix-en-Provence that Rewald met the German painter Leo Marchutz, who had photographed many of Cezanne’s motifs in the Provencal countryside. Rewald joined Marchutz with his newly acquired Leica on these “motif-hunting” excursions, and their work led to a greatly expanded understanding of the painter’s site-specific landscapes, many of them now lost to urban encroachment.

In 1939 Rewald was interned in France as an enemy alien—a night-marish irony considering Rewald was Jewish and his family had already fled Germany for England. Two years later, he and his wife barely escaped the Nazi invasion of France by booking passage from Marseille to New York in a Casablanca-like getaway.

Once in New York, Rewald was immediately hired by the Museum of Modern Art, where he directed a number of exhibitions. MoMA’s pioneering director, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., who helped Rewald secure his American visa, took the young scholar under his wing and provided him with a monthly stipend so he could finish his groundbreaking study History of Impressionism. It was published by the museum in 1946 and remains the most important and widely used text on the subject.

Rewald became a U.S. citizen in 1947 and gradually carved out an impressive academic career as a tenured professor at the University of Chicago. In 1971. he was honored with a distinguished professorship at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. When he retired in 1984, the university established a chair in his honor.

In addition to his ongoing devotion to Cezanne scholarship—including contri butions to catalogues accompanying more than a dozen Cezanne exhibitions – Rewald wrote numerous books and mono-graphs on artists from Pierre Bonnard to Georges Seurat.

Yet he never confined himself to the ivory tower of academia. He was active in the international an market and worked for many years as a paid advisor to the late John Hay “Jock” Whitney as well as Paul Mellon. two of the country’s greatest collectors of Impressionist and post-impressionist paintings. Both men relied on Rewald for guidance when donating works of art to museums.

Throughout his life, Rewald made frequent trips to Provence. In 1953, he was instrumental in saving Les Lauver, Cezanne’s last studio, from the developer’s bulldozer. Tipped off by writer James Lord, Rewald organized a com-mittee of American art aficionados and bought the property for a song. The studio was—and still is—much as Cezanne left it, although the artist’s widow and son had sold off any remaining art work, including one of the monumental “Bathers:’ shortly after the artist’s death.

In 1960, Rewald sold part of his collection of Impressionist and modern works on paper and used the proceeds to acquire a hilltop citadel in Menerbes, about an hour from Aix. He spent summers and Christmas holidays there, adhering to a strict work schedule and making frequent forays into the Provencal countryside. In 1986, the French Government made Rewald an Officer of the Legion of Honor, citing him as a “national treasure of France.” In a less formal but no less genuine tribute. the City of Aix named a street after the art historian and made him an honorary citizen.

But glory was clearly of minor importance to this dedicated scholar. In the words of Robert Morton, director of special projects at Harry N. Abrams and Rewald’s longtime friend and associate,”His interest was always in truth, not in ego.”