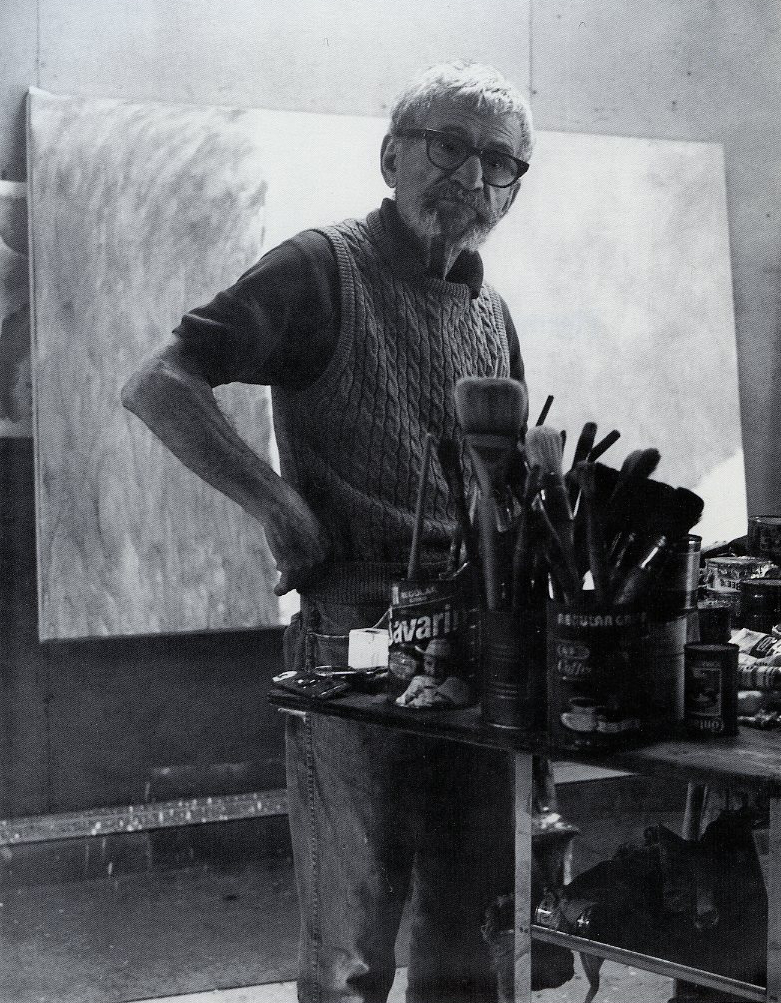

Herman Cherry, 1989, photo courtesy: Regina Cherry

Herman Cherry is a survivor of that moment in American art when New York lifted the art mantle from Paris. It was an art world coup. Because of that frenetic time—the spoken volumes of heated conversations, the endless nights drinking and arguing over tumblers of whiskey in the Cedar Street Tavern—a number of the major figures died young or violently. The chroniclers of that time—the post-war years of the late 1940s and early 1950s—were in a hurry too and things moved too fast for them to realize, let alone record the “history” being made.

Cherry is one of the personalities that the art critics, historians, journalists, and filmmakers contact to find out what happened back then. Often, the questions are aimed at the icons of the age—David Smith, Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, Philip Guston, and so on. Cherry performs that cultural duty with distinction and wit. His remembrances are recorded in biographies of famous men, in films that salute those myth-making artists who became rich and famous after years of numbing poverty or worse, grinding neglect.

This essay touches on some of those tales, but the spotlight stays fixed on Cherry, taking us back to his roots in Philadelphia and his early odyssey west to Los Angeles. For Cherry is a great traveler-adventurer. Many times he has alluded to the irony that he became a painter and not a writer. That too is qualified by pithy and hard-hitting stints at art criticism and a gentler collection of largely unpublished poems. The point here is to introduce Cherry as a major American abstract artist who found his path slow and arduous. Luckily for us, he painted most of the way.

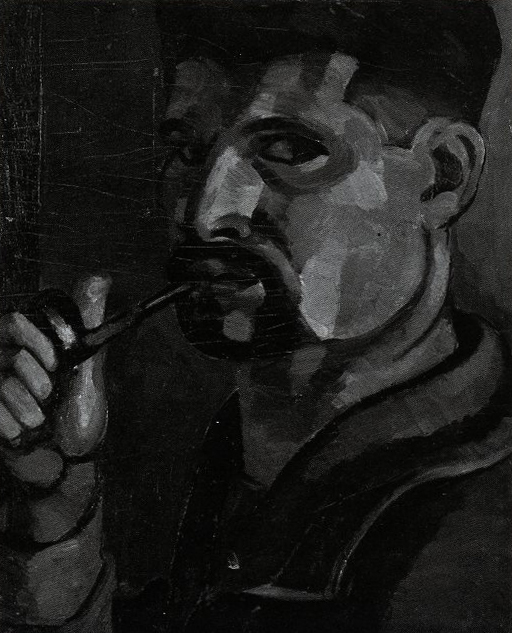

Herman Cherry, Self Portrait, oil on canvas, 15 x 12 inches, 1927

Decades before Cherry made his first mark in New York at the age of thirty-eight with a one-man show in 1947 at the Weyhe Gallery (garnering favorable reviews and even a splashy three-page spread in Life for his inventive, Calder-inspired mobiles that he called Pictographs), he studied painting with two of America’s best-known modernists, Stanton MacDonald-Wright in Los Angeles and Thomas Hart Benton in New York. There is a strong connection between Wright and Benton. Both studied painting in Paris; they even roomed together. While Benton quickly shucked his modernist beginnings to set up shop in New York at the Art Students’ League, Wright and Morgan Russell perfected a movement of their own that became known as Synchrony, a Cubist-influenced direction that championed prismatic color and made a big splash at the famous Armory Show in New York in 1913. As he demonstrates again and again, Cherry has a magnetic knack of finding the best and the brightest, of stumbling— with balletic grace—into the lap of the avant-garde, whatever the medium.

When Cherry was not hawking papers or parking cars for a living in Hollywood, he attended Wright’s weekly evening classes. Cherry pointedly says, “It wasn’t that he taught me color. He made me see color.” So this literally starving artist-to-be, who first saw a painting, Benjamin West’s Death on a Pale Horse, at the Pennsylvania Academy of Art when he was still in short pants, embarked on his journey to abstraction, starting late, like Philip Guston and Franz Kline, to abandon figurative elements and joust with the non-objective.

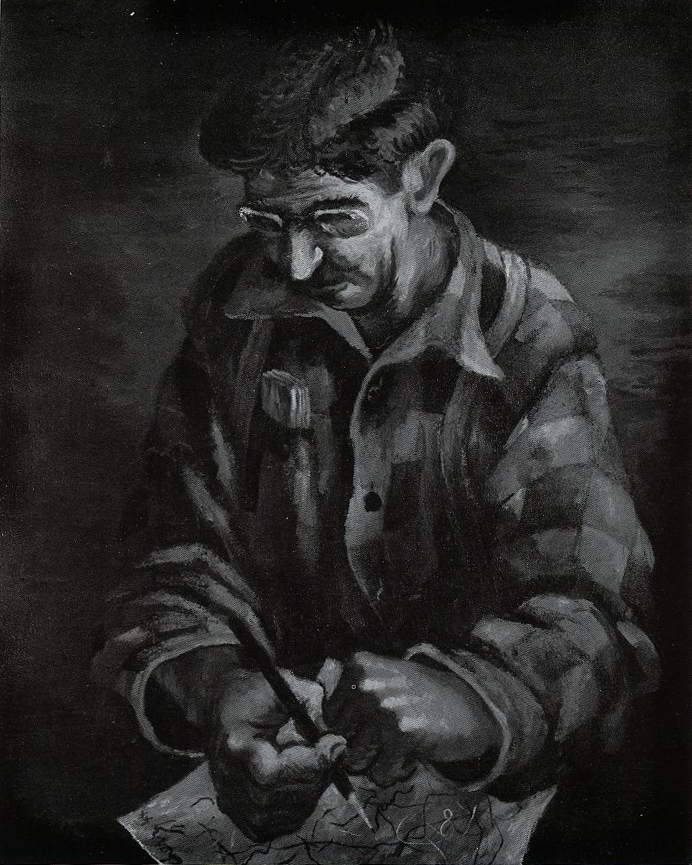

Herman Cherry, Portrait of Archie Musick, oil on canvas, 20 x 15 inches, 1947

The year is 1927, give or take. A handsome face, goateed and intense, sucking on a pipe, stares the viewer down. Cherry’s self-portrait (cat. no. 1), dappled with dramatic light, is decidedly French-inspired, a clumsy Cezanne card player with a strong hand cradling his pipe. It is not hard to imagine that the sturdy-looking youth would assist a few years later in Benton’s epic New School mural, Modern America, or for that matter resemble one of the rough cardplaying characters in its cycle of cross country vignettes. Given Cherry’s touch-and-go existence, it is miraculous that any of his early works survive. They are—on the whole—vivid and sensitive to the avalanche of influences that Cherry absorbed.

Study of El Greco (cat. no. 3) mirrors the artist’s continuing quest to learn from the masters, whether they be Giotto or Matisse. A kind of rumbling expressionism informs his early work, a sensibility that bridged his eventual leap to abstraction. You can see it in his floating Lovers of ca. 1938, about to crashland onto a cloud,

In between stints as a student of Wright and, later, Benton, Cherry took the first of many European trips. His first one, in 1929, resembled a hellish chapter out of B. Traven’s Ghost Ship. Through a friend in Wright’s class, Cherry boarded a ship out of San Pedro, California, working as a cook’s helper and steamed off to northern Europe. By the time he jumped ship somewhere in Germany, it was too late to realize that a young American without a passport was in hot water.

Cherry survived in Germany for almost a year, living near a soup kitchen and doing odd jobs for practically nothing. Germany was unraveling at the seams, and Hitler was working the streets. It was the kind of trip that most “art students” never experience, even in their most vivid nightmares. Cherry got back to the United States and hitchhiked north to New York. The chilling horror of pre-war Germany as well as the harsh beauty and relief he found back in New York eventually found their way to canvas, not in a figurative or literal way but somehow distilled through his own brand of humanism.

Cherry’s portrait of his close friend Archie Musick (1944) (cat. no. 6) depicts this artist outdoorsman who abandoned New York for the canyons of Colorado, immersed in a nervous lined abstract drawing, his black pencil hovering like a divining rod over the roadmap of lines. He seems to be ideal casting for Bentonesque regionalism, but Musick played a crucial role in getting Cherry started in New York at the outset of the Great Depression. The composition’s most striking attribute is the glowing red checkerboard squares of color that are part of Musick’s flannel shirt. Stripped from the rest of the canvas—and held up by the vertical blue bands of suspenders—the multihued squares can be viewed as potent precursors to Cherry’s future work. In the meantime, Abstract in Red Squares (cat. no. 15) from 1952 and the more complex Color Clusters from 1955 (cat. no. 22) seem to be torn from the same fabric as Musick’s shirt. Indeed, Cherry’s journey to abstraction can be plotted along a graphpaper map of increasingly abstracted still lifes after a lengthy stay in Paris in 1948-49.

By the time the painter returned again to New York his marriage had dissolved, but his paintings took on new life, shedding their representational skin for increasingly Cubist and Surrealist distorted imagery. Temporarily established in Woodstock, the painter finished his last works of still recognizable objects with Lamp Still Life, Still Life, Woodstock, and Stove Painting, the lot executed in 1950 (cat. nos. 9, 10, 11).

Herman Cherry, Still Life, oil on canvas, 42 x 28 inches, 1951

Cherry dropped his wittily conceived mobiles in midflight after two solos and dug into harder ground, as if scared off by or suspicious of the raves they attracted in the burgeoning art press. (“If you have inhibited friends who feel they must tag all modern art with respectful seriousness, you should take them to the Weyhe Gallery where their laughter will be quite de rigueur,” wrote The Art Digest reviewer Judith Kaye Reed in the April 1947 issue. “There are 23 other mobiles—all very clever, very gay and, of course, very sophisticated.”)

A double portrait, Cherry Twice, by his good friend Fletcher Martin from the year earlier shows Cherry in a high-backed chair, outfitted in his Woodstock uniform of blue jeans, sandals, vest, and pullover shirt. Dark and dimple-chinned with a bushy mustache and Afro-like hairstyle, the artist sits with sketchbook in lap, surrounded by crumpled sheets of discarded drawings, rusty car springs, and a ghostly jawbone. Two of his pictograph-mobile creations of wire and colored glass hang in the air like resting marionettes. Another view has Cherry standing, fiddling with one of his sculptures.

In a number of interviews with this writer spanning a ten-year period, Cherry often described his process of painting as akin to spelunking in dark and dangerous terrain. And it became clear that Cherry’s poetic metaphors are often backed up by real-life experience.

By a marvelous quirk during his stay in Paris (“I wasn’t painting in Paris:’ says Cherry, “just living it up and suffering”), he met the accidental discoverer of the Lascaux Caves in the Dordogne region and was among the first Americans to view them, years before tourism diluted the descent and damaged the uncannily preserved prehistoric wall paintings of racing bison, deer, and horses. Cherry teamed up in Paris with then-obscure filmmaker Alain Resnais (Hiroshima Mon Amour, Last Year at Marienbad, and Providence) for an exceedingly low-budget film on the discovery, one that never got made even though Cherry “scripted” the adventure.

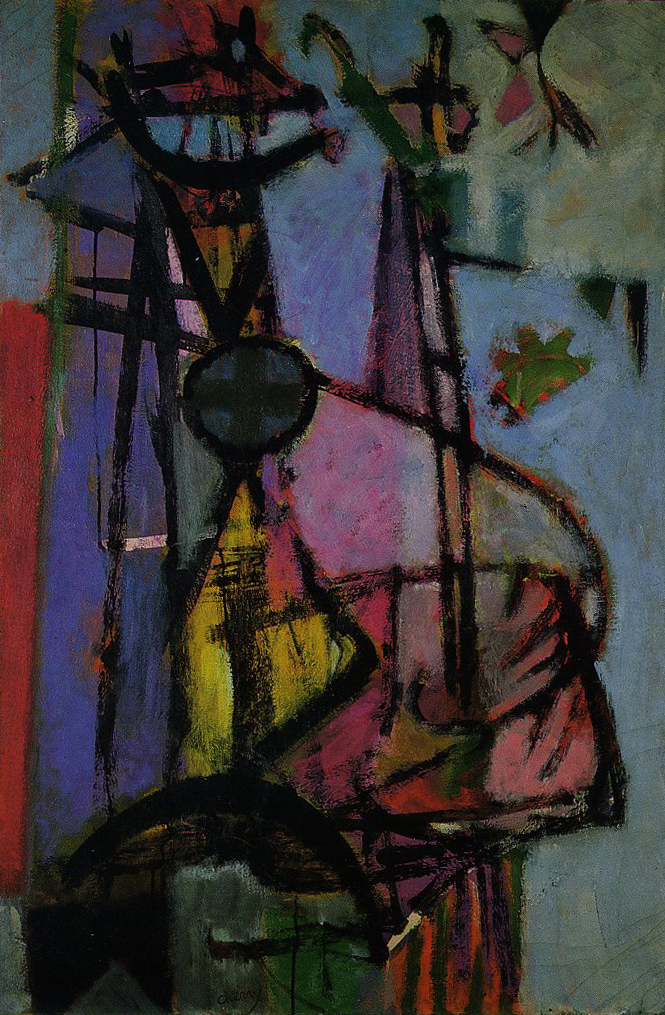

Herman Cherry, Truncated Movement, oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches, 1959

His moody and magically luminescent Black Cave (Black Painting #6) from 1954-55 (cat. no. 20) captures the terror and elation of interior exploration. The rich and lusty enamel of the black pigment sparks against underlying films of smoky blues and bursts of incendiary reds. For added texture—perhaps to bring the viewer closer to the experience—the artist added coffee grounds to the volcanic and pocked areas of paint, a signature gesture echoing his longing for the flotsam and jetsam of found things.

Cherry’s continuing fascination with Lascaux and the mystery of those anonymous artist hunters mirrors in degree the late British travel writer and novelist Bruce Chatwin’s incredible journey detailed in his book In Patagonia, in which the writer treks down the length of Argentina in search of the hide of a prehistoric beast. Significantly, Cherry did not attempt to recreate the stunning images as Elaine de Kooning would years later, but chose instead to incorporate that elusive essence into this newly emerging vocabulary—attempts that often resulted in torn-up or burned canvas.

During one afternoon’s talk at his large but no-frills loft on Mercer Street in Manhattan’s SoHo, Cherry stood by the kitchen stove, stirring his “range coffee:’ an adapted campfire process that produces a strong and gritty beverage. I watched him twirl the sludge with a teaspoon, his calibrated and seemingly obsessive stirring—like a boxer wearing down his opponent with hundreds of jabs—and was reminded of my Sisyphean task ahead of piecing together some eighty years of hard living and a significant body of paintings and works on paper, many of which had been stored for years, rolled up in the darkness of his cavernous basement. Cherry talked about the resurrected interest in his work and what it was like to go back and examine it while still actively engaged in painting new works:

“My life was so difficult from a money-making standpoint…I think that’s partly why my work has had fits and starts, flashes of something going to happen and something gets in the way again…It’s only been in the last ten years that I’ve been able to make enough living off my paintings to be able to maintain continuity. Maybe it was the bringing together of these various periods—which were truncated at one time or another—when I couldn’t develop certain areas, so now I go back to them to see what I might have missed.”

Asked to amplify his remarks on what kept him struggling at finding his footing in abstraction, Cherry stirred the pot some more and said, “The abstraction of painting is a very, very difficult fence to climb. It took me a long time to see non-objectively. . . I went through an exploratory period until I found my own idiom. I’m influenced by the past in so many different ways which have since merged into my own past:’ Cherry stopped for a moment and told me to read Gauguin’s letters to see how the artists of that time rushed to each other’s work, of excitement that was rekindled with the Abstract Expressionists.

“I don’t think about it today when I’m working. I always seem to be in a landscape I was never in before so I have to rediscover the way to get to it, that place I vaguely see. I have to make my own roads and sometimes I go the wrong way. But I’m always willing to take the chance. If I discover a straight road, then I’ll get bored. Then I look for other ways to get to it. It’s very difficult to explain but you have to create a struggle that could be made easier—to create situations that are untenable. How else can you get energy into paintings?”

The low-watted glow of Across the River (1955) (cat. no. 21) illuminates the interlocking rectangles of muted color that rumble across the expansive blackness like a jazz-powered freight train. With multiple allusions toward landscape and distant views, the painting immediately transports the viewer past any imagined semblance of crumbling piers or half-submerged boats to a grand open space. At the same time, culminating a series that began with Night Promenade (cat. no. 19, which debuted at his first solo at the Stable Gallery in 1955 and still retains an honored spot in the artist’s Spartan studio), the paintings appear uncharacteristically subdued, barely shrouding the subterranean pentimento of hotter colors. Like a snapping dog restrained on a short leash, the energy in the picture can barely maintain its decorum—despite the geometric economy and the improvisation of finely tuned chords of low-key color, from metallic grays to royal blues.

For Cherry’s first solo painting show at the cutting-edge and now legendary Stable Gallery, the announcement card was printed on glossy black stock with the artist’s surname barely visible in deep purple. But for the following few years that name would receive extensive exposure in solo and group shows—including important showcases like the Whitney Museum annual exhibitions of contemporary American paintings (with four appearances in 1951, 1955, 1956, and 1958 when the museum was on West 54th Street, behind the Museum of Modern Art) and in reviews that democratically corralled the new talent along the cooperative bank of storefront galleries on East 10th Street, then a veritable spawning ground of intense artistic activity. What caused his popularity to wane is anybody’s guess, but at that moment Cherry’s name was in the air, a firecracker presence in the relatively small world of Abstract Expressionists, one that moved from loft to bar to jazz club, much of the action occurring at night.

Fortunately in the late 1970s, after a self-imposed and seemingly permanent break from painting, Cherry picked up his brushes again, this time without distraction or torment He had long since worked the night life out of his system and was married to his second wife, photographer and painter Regina Cherry. He hooked up with a then rapidly growing federally funded CETA (Comprehensive Employment and Training Act) Artists Project. he was awarded commissions to execute murals in the boroughs of New York. (Artifice, a six by twenty-five foot mural for St. Malachy’s Church in Manhattan is one stunning example.) With his experience as an easel painter with the WPA in southern California, Cherry quickly became an authoritative voice and sought-after senior counsel. Young artists—even those unaware of his major contribution to and membership in the New York School—were rightfully dazzled by his painting.

Crystal Heart I(cat. no. 55) is a painterly mirror reflecting the artist’s long march to a territory he could genuinely call his own. Still lugging some of the nostalgic freight of past skirmishes, the broad bands of dusky color engage coal-fired lanes of red. The alternating salvos of low- and high-keyed colors trigger a kind of palpable oscillation—new to the work— that bonds the opposing forms and outlines their respective negative spaces. Cherry begins to loft his non-objective forms into an illusory semblance of sky and earth, water and mass. Hovering over the surface like an alien dervish is the crystal form sheathed in a dazzling shade of azurite blue. The painting represents Cherry’s clarion call (in-progress) to his own brand of synchrony, neither post nor two.

Viewing his oeuvre in chronological sequence—especially after the black night paintings and his abrupt jump to bright, almost garish colors where, in the artist’s words, “everything was scattered, broken, sharp and bright”- reveals his choreographic power to animate painterly gesture. As if shifting a car into reverse, Cherry sped backward, purging his subtle nuances of color and running over his forms, crushing them without a moment’s remorse. Implosion, Reds on Green, Shapes Moving Downward, and Truncated Movement swept in with tidal force (cat..nos. 30, 26, 28, and 32). Just as he would later accomplish in his River series, the artist created new steps, refining the familiar, chopping off the excess, coming up with taut and emotive passages. With Zen-like accuracy he achieved what the sculptor and critic Sidney Geist once called “making equivalents for spiritual states.”

Cherry’s long-term fascination with the Far East (first sparked by his classmate and lifelong friend, painter Hideo Date), in both Haiku poetry and the miniature painting of the Muslim Iviughal empire, has emerged as a potent influence, replacing the Sturm and Drang of Abstract Expressionism with another kind of power.

The River series, for example, did not see canvas until hundreds of experiments on paper had jelled (cat. no. 44). Cherry’s comment that the title “has nothing to do with the river; I don’t know where I got the image,” is his somewhat typical way of counter-punching with irony. He alludes to the possibility of landscape, that the paintings “seemed to have a free flowing thing,” and that he might have gotten the image from all the flying he was doing in the 1960s, shuttling across the country, picking up guest-teaching gigs at universities in Mississippi, Illinois, Kentucky, and California. At that rare moment of confession, the candy-striped curve in Cerulean Blue No. 5 (cat. no. 42) shouts hallelujah.

The mature Cherry comes into his own when he encounters the less visible contours of the non-objective world. Never completely abandoning the modernist web of Cubism, Cherry says of his recent work: “It looks free and loose when you look at it but the structure is there. Otherwise, it would just be nothing!’

Cherry’s slim volume of poetry, Poems of Pain—And Other Matters, bridged the contemplative period between his abandoned Window series and his decision to resume painting. If the cycle had ended there his body of work, based on the grand suite of his night paintings alone, would hold a place in the pantheon of New York School painters. But Cherry came back and vanquished his demons, producing a new generation of paintings. With the strength of ten solo shows in as many years Cherry has distinguished himself as a master colorist of the non-objective world.

Herman Cherry, Push Comes to Shove, oil on canvas, 60 x 60 inches, 1989

Mosque, from 1988 (cat. no. 66), is assured and dangerously sublime. His feathery stroke (a signature really) carries not just pigment but a sorcerer’s wand of light. It is not sun or lamp light but Cherry’s own incandescence illuminating the canvas, darting between silky layers of pigment that throb with measured beats. The painting glows like a wall of mosaics in Cordoba hit by a chink of light at a particular moment in time. It is an uneasy sensation, the lightness of being framed by the painted architecture, carving the canvas with structural columns. Without a hint of reference the painting’s majestic color and dreamy solitude conjure up fraternity with Monet’s Giverny and Cezanne’s Mt. Sainte-Victoire.

Push Comes to Shove (cat. no. 69), completed in 1989, is an amalgam of Cherry’s painterly chemistry. Acrobatically lithe, a troupe of hard edged forms converge at an intersection, triggering a kind of balletic gridlock without the cacophony of horns—a delicate balance between chaos and harmony glimpsed the second before the crash. The chiseled forms are not heartless or taped with Mondrian’s unforgiving lines, but sensually softened with all over dabs and touches resembling the untrimmed deckle edges of fine handmade papers.

The Cherry of the eighties is his own man. At times the paintings seem to represent flags of continents or, like his Cenotaph, an abstract epitaph of another time, either future or past. Cherry’s deceptively simple forms and high keyed incursions of color lay claim to the canvas territory with instantaneous authority. In the end, Cherry’s paintings live up to the aura and breadth of his extraordinary life.