The once confidential legal documents known as the Panama Papers have exposed a global game of offshore dealings, shining an unwelcome light on some high-profile art world players.

Arnedeo Modigliam’s, Seated Man with a Cane, 1918, has been the subject of a protracted lawsuit

The Panama Papers comprise some 11.5 million documents leaked from the archives of Mossack Fonsecaa Panamanian law firm specializing in establishing offshore entities outside the radar of tax authorities. Released in April through the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and various major newspaper outlets, they have not only exposed the secret dealings

of politically connected figures but are also shedding some unwanted light on several clandestine art-related transactions.

Topping that list, at least in terms of headline value, was the storied November 1997 Christie’s auction of the Collection of Victor and Sally Ganz. The sale made a record-breaking S206.5 million, powered by a handful of star lots—among them Pablo Picasso’s Le Reve, 1932, which sold for a record S48.4 million. From the papers, a more apt description of the sale may have been “property of Bahamas-based British billionaire currency trader and mogul Joe Lewis,” who owned a big stake in what was at the time a publicly owned Christie’s. It seems he bought the Ganz collection six months before the November sale for a more reasonable S168 million. Apart from a one-line footnote in the Ganz sale catalogue in which the house noted that it had a financial interest in the property, few souls were aware of the transaction, which was secretly brokered through Spink & Son, a British-based, wholly owned Christie’s subsidiary.

“I would say,” said a former Christie’s executive, “other than then chief executive Chris Davidge and possibly one of the lawyers, I don’t believe any senior person at Christie’s knew about the actual mechanics of the deal.” Davidge was the CEO who was later granted immunity from prosecution after bringing the price-fixing details between Sotheby’s and Christie’s to the attention of the U.S. Department of Justice in 2000. He also partnered with Lewis in 1999 to try to buy Christie’s, but was outbid by Francois Pinault, who quickly delisted the house from the London Stock Exchange, taking it private later that year. Even with the revelation that Simsbury International Corporation, Lewis’s offshore trust sheltered on the Pacific island of Niue, was the listed buyer, sale details are murky.

“Christie’s has not had the opportunity,” said a spokesperson for the house, “to review the same documents that the ICIJ holds, but as the original Guardian article on the matter makes clear, there is no suggestion that the sale arrangements were incorrect or outside of auction standards governed by law. All necessary financial disclosures were made at the time of the sale.”

Also named in the papers are David Nahmad and members of his art-dealing family, who bought Picasso’s Les femmes d’Alger (Version “H”), 1955, for a hammer price of S6.5 million in the Ganz auction. In 1995, Mossack Fonseca set up a shell company for the Nahmads known as the International Art Center (lAc), of which David Nahmad is reportedly listed as the only shareholder. The ‘AC has been in a long-brewing lawsuit filed in various New York courts against the Nahmads by Philippe Maestracci, the sole heir and grandson of the late Paris-based art dealer Oscar Stettiner, whose collection was seized by the Nazis and sold off through middlemen in a series of auctions beginning in 1941. Maestracci—via George Gowen, the administrator of the Stettiner estate—is

seeking the return of Amedeo Modigliani’s 1918 portrait Homme assis (appuyé sur une canne), better known in English as Seated Man with a Cane. It was painted when the artist was in Nice having fled Paris and the brutal German occupation of France in World War I. It was first exhibited at the 1930 Venice Biennale, where it was titled Ritratto d’uomo (Portrait of a Man).

The IAC has owned the work since David Nahmad acquired it at Christie’s London in June 1996 for 62,091,500 (S3.2 million). It’s appeared in several exhibitions since then, including “Modigliani: A Bohemian Myth” at the Helly Nahmad Gallery in New York in 2005 and in 2006 at the Royal Academy of Arts’ blockbuster “Modigliani and His Models.”

In November 2008, two months after the global stock market meltdown, the portrait was put up for sale by IAC / the Nahmads-sans mention of property title in the catalogue—at an Impressionist and modern art evening sale at Sotheby’s New York, where it bought in at S15.5 million against an S18 million-to-S25 million estimate. The provenance trail in the sale catalogue included the following: “(possibly) Stettiner, Paris (by 1930)7 and also cited the 1930 Venice Biennale exhibition to which Stettiner had loaned the painting.

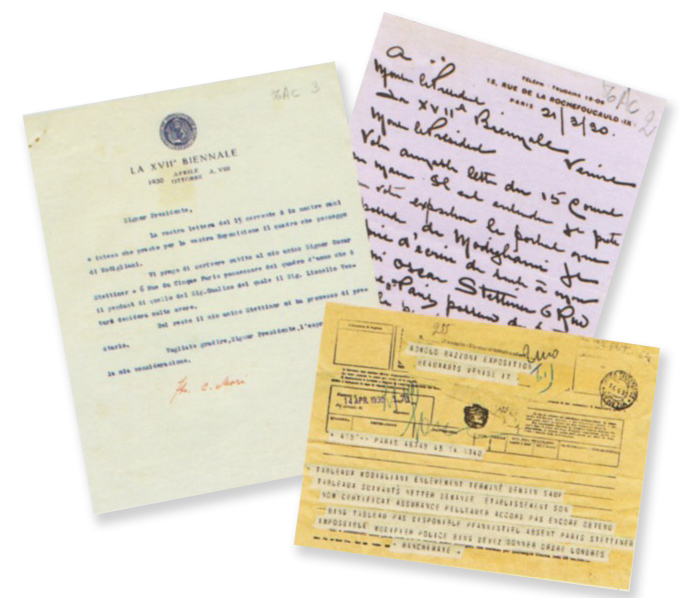

A selection of documents preserved in the archives of the Venice Biennale attest Paris dealer

Oscar Stettiner as the rightful owner of Modigliani’s Seated Man with a Cane, which he lent to the event in 1930.

James Palmer, an international consultant and founder of the Toronto-based Mondex Corporation, a firm that specializes in the recovery of Nazi-era stolen art, is working with Maestracci on a contingency basis. Palmer provided Art+Auction with facsimiles of documents that appear to corroborate the Stettiner claim regard-ing the early ownership of the Modigliani. Those documents, along with the Panama Papers information, prompted the Geneva prosecutor’s office in early April to raid the Freeport storage facility where the Modigliani was kept and to have the work officially sequestered, meaning the painting can’t be removed by IAC. (Several early news reports erroneously stated that the painting had been seized by Swiss authorities, while Mondex even issued a press release hailing that nondevelopment.) In a Wall Street Journal article following the sequestration, David Nahmad said the issue about the creation of the IAC vehicle “wasn’t relevant to the lawsuit” and that IAC was simply set up “for discretion purposes. Everybody knows we buy under IAC.”

Pressed to explain the reluctance on the part of the family to return the picture Richard Golub the attorney for David Nahmad and IAC, said, “The press has made a big deal about it becuase IAC is a Panamanian corporation, but the plantiff has not focused on the issues and hasn’t been focused on the issues for fie years. Is it or is it not a painting that belonged to a Jewish family in the Second World War. We say we don’t think it is, but they’re trying to embarrases the Nahmads into settling the case. It’s not going to happen.” Golub went on to say, “We’re not making any effort to hide the painting; it was bought at Christie’s London by a citizen of Monaco, so what does the U.S. have to do with this? Nothing.” In an e-mail following the Swiss action, Palmer said, “We are now several steps closer to resolving this matter and finally enjoying the justice that Mr. Stettiner’s family has been seeking for more than seven decades”

The Panama Papers are also providing a window onto the dealings of the little-known Wilton Trading company. The entity, which belonged to the sister-in-law of the late Greek shipping tycoon and art collector Basil Goulandris, is believed to be harboring a 53 billion hoard of Impressionist and modern masterpieces.

Aspasia Zaimis, a niece of Goulandris and his wife, Elise, is one of six heirs of the childless couple and is waging a multi-front legal battle in Switzerland, seeking her share, or one-sixth, of some 83 masterworks collected by her uncle, the whereabouts of which are unknown. It is alleged that Goulandris sold the works, among them six paintings by Van Gogh and major pieces by Cezanne, Manet, and Renoir, to Wilton in 1985 for a decidedly paltry S31.7 million. Some of those works have sold in turn more recently through Wilton or related shell companies, including Van Gogh’s Nature morte aux oranges, 1888, for 620 million to California marketing guru Greg Renker.

New York art dealer Ezra Chowaiki has financed part of Zaimis’s legal battle with Wilton and its representatives, including Peter John Goulandris, a nephew of Basil Goulandris, for first dibs on paintings that may be returned to Zaimis. “The Panama Papers thing,” says Chowaiki, “has gifted us this information about where some of the pictures have been sold over the years, who sold them, for how much, and to whom. That’s amazing, and I was astonished we could get that information.”

Still other art stories are emerging from the papers, including that of Xitrans Finance Ltd., an entity controlled by Russian oligarch and art collector Dmitry E. Rybolovlev; it was used to transfer artworks from Switzerland to safer havens, in Singapore and London. No doubt, more tales are yet to be revealed.