Squash, the frenetic racquets game akin to jai alai, handball and billiards, is moving out of its Ivy League closet into the booming Court of public leisure sports.

Squash, the frenetic racquets game akin to jai alai, handball and billiards, is moving out of its Ivy League closet into the booming Court of public leisure sports.

Of the 30-odd squash facilities in the metropolitan area, only one is public. the Filth Avenue Racquet Club. Three more public facilities are currently under construction–the Park Place Squash Club, the Manhattan Squash Club, and the Uptown Racquet Club.

“Public” in the elitist jargon of squash racquets is a pay-as–you-play proposition with a yearly membership fee. Unlike the New York Athletic Club, The Princeton, Yale or Harvard Clubs, there is no initiation fee or pedigree necessary.

The rnere mention of squash elicits images of polo or yachting, perhaps a scene from Love Story. The origin of squash, though, goes back to the early 1800s and the debtor prisons in England. Tailoring their game to a claustrophobian’s nightmare, pre-mastercharge victims thwacked a stringy, hard ball with a primitive wood racquet against peeling slate walls.

From prison the game moved to Harrow and the outer limits of the flourishing British Empire—Australia, New Zealand, India, Pakistan; Egypt and Canada. The ball dribbled towards New Hampshire in the late 1890s and found a comfortable niche in Ivy League schools.

The first public squash courts in the U.S. were built in the fall of 1973 by Squashcon, Inc., in Berwyn, Pennsylvania. Squash-con’s head of promotion, Nancy Kropp, commented on the tremendous market for women in squash. “If you can’t make it on a tennis court, if you’re tired of being intimidated or inhibited by your boyfriend or husband,” says Kropp, “squash is a joy. You don’t waste time running around, chasing stray balls and men and women can compete better. It’s not just a power game like tennis.” Kropp says squash has spread like wildfire in the Philadelphia area and women are free from discrimination on the public courts, a situation unheard of at private country clubs.

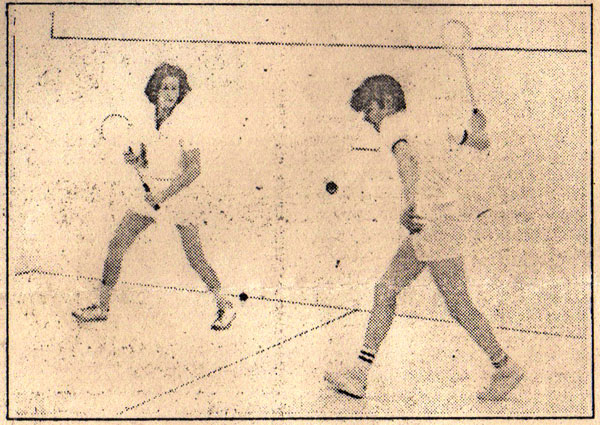

The rudiments of squash can be learned in an hour’s time. Follow-ing a green or black ball in a white room with horizontal red boundary lines can lead to dizziness and insomnia, but with the proper attire (gym shoes, shorts, t-shirt and trusty squash racquet) the neophyte can whack and be whacked at at will. Similar to the green felt table of billiards, the squash addict will vie for position at the center line of the court (called the “T”), and with malice and forethought place the shot in cunning disrespect of his opponent. Medical types liken 45 minutes of squash exertion to two hours of tennis.

Played inside a topless box of wood, concrete and fiberglass combinations, with dimensions somewhat less than half a tennis court (181/2 ft. x 32 ft.), squash is a ferociously militaristic game, involving chess-like strategy with boxing’s jabs, roundhouses and uppercuts. Unlike boxing these “punches” are called nicks, boasts and lobs.

Players crouch side by side and take turns thumping a seamless rubber ball 1.75 inches in diameter against four walls in infinite varia tions until the point is lost or won by muffing or putting away a shot.

This can be accomplished by miss-ing the ball entirely (a cardinal rule, keep your eye on the ball), or let-ting it bounce twice. In a matter of minutes both players can be gasp-ing for breath and drenched in sweat.

Roland Oddy, squash director designate of the prenatal Manhattan Squash Club (expecting to open in July of ’76) says, “What has happened to tennis will happen to squash. It just depends on how fast.” Oddy, past president of the Metropolitan Squash Racquets A-sociation, feels squash is played three different ways, for expertise, exercise and enjoyment.”

Mark Tascher, vice-president of the ‘enterprise that runs the Fifth Avenue Racquet Club, believes squash has “become another leisure sport, a place for people to get an intensive amount of exercise within an urban setting in a short time for a reasonable leisure dollar. It’s a perfect outgrowth,” says Tascher, “of the boom in tennis, a sport easy to catch on and play reasonably well quickly and with a low initial investment.”

Dr. Milton Brothers (mate of Joyce), originator of the Westside Y Squash Racquets Club, predicts a tremendous growth in public squash. “The sport has changed from an elitist game,” says Dr. Brothers, “to an accessible activi-ty open to a wide segment of the population.” Commenting on Harry Saint’s Fifth Avenue Club, “It took a lot of balls, frankly, to open a public club in Manhattan.”

At 10:00 P.M. on a weekday evening, on the 8th floor of a loft building in the deserted garment district, the seven courts of the Fifth Avenue Racquet Club are booked solid. Couples cluster in the lounge area, imbibing a cut-throat game of squash through the glass-paneled back viewing wall of the exhibition court. Others are lost in greedy contemplation at backgammon tables and a few sweaty participants grope for breath over a fetid Virginia Slim. The sucking sound of a walloped trajectory of green rubber caroms off a stark white wall, the sound muffled by the poured polyurethane goo binding the wood and concrete front wall. Off in a changing room an exhausted player Avenue Club, considers public squash “a very risky venture. Real estate is enormously expensive in Manhattan,” relates Saint, “every deal is different and what you pay for one space could vary by a factor of 10 in another. If squash continues to expand people will get’ a good idea of what it costs but New York City will always. be a different case.” Saint’s new venture, the Uptown Racquet Club at 86th & Lexington will lure more women and children from the upper East Side to the game. “New York City can support lots more clubs,” says the squash innovator of 37th Street.

Downtown in the financial district, Jeff Botz, squash pro, con-tractor and promotor of the game, stands in a plaster mist of five behind-schedule squash courts. Botz has cartons of “get squashed” t-shirts, promotional posters for the Park Place Squash Club hung in subway stations and radio spots over WKTU-FM. There are 150 new members clawing at the door. He calls the timing terrible, basically a month behind. His rates will be the lowest in town during the weekend—non-prime-time hours when Wall Stretchers flee for suburbia and loft athletes lope to new quarters between Church and Broadway. While dueling with his construction foreman, Botz muses over the conspiracy of money and the powerful capitalist orientation of the game. Once a pro at the restricted New York Athletic Club, Botz equates 100 hours of playing time on a public court with the price of one private membership.

In the curved tinted glass of the W.R. Grace Building is the skeleton of the Manhattan Squash Club. With blueprints calling for 10 singles courts, one doubles, two racquetball/handball courts, restaurant, bar and gymnasium, the Manhattan Club plan is the most ambitious in town. General partner Leon Van Bellingham signed a 20-year, 51/2 million dollar lease for the 22,000 square feet of space, boasting 24-foot-high ceilings and an independent 120 ton air conditioner to cool the facility’s 7:00 A.M. to 11:00 P.M. hours. With a sweeping view of Bryant Park in the daytime and lit-up Empire State Building at night, the club hopes for hot success. Van Bellingham anticipates 4000-5000 members and a home away from home for wayward executives and corporate weight watchers.

Squash Pans salivate for the day when pro squash is televised in the states. A common occurrence in squash-crazed Australia, the game poses technical trouble for slow-eyed TV cameras. The ball travels too fast and does not show up well on a. TV screen. Recent innovations such as a camera window in the “telltale” (the 17-inch-high tin strip on the front wall that sings at a low blow) could eradicate this sticky dilemma. Enthusiasts agree that the high caliber of pro squash outshines the spectator thrills of tennis and, most certainly, Sunday golf.

Equidistant from Union Square and the Flatiron Building squats the Paragon Sporting Goods Company on Broadway. Albert Blank, the owner, has been selling squash racquets there for thirty-five years. Blank is enjoying a brisk business in new racquets and restringing old ones. He smiles benignly at a question of how many squash racquets are sold in a week and murmurs he has 40 models to choose from, with twenty different types of string. Hedging a question, “Is squash booming?”, Blank chuckles and says, “After all, it’s not like selling ice cream cones.”