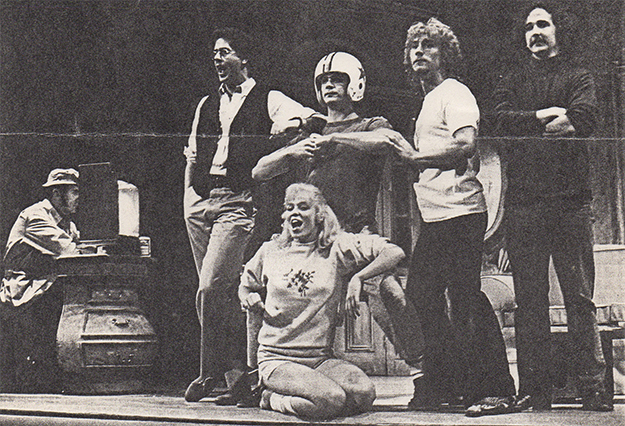

Boopsie’s flat on her leotarded back, doing Jane Fonda abdominals on the livingroom rug of the Walden Commune. Her beau, B.D., decked in a lime-green football helmet, screeches in disgust that she’s sweating on the rug. Zonker builds a beer-can pyramid while contemplating his retirement from the tanning

Boopsie’s flat on her leotarded back, doing Jane Fonda abdominals on the livingroom rug of the Walden Commune. Her beau, B.D., decked in a lime-green football helmet, screeches in disgust that she’s sweating on the rug. Zonker builds a beer-can pyramid while contemplating his retirement from the tanning

circuit. Mike’s in the kitchen fussing over seaweed salad and rehearsing his third-draft marriage proposal to J.J Marvelous Mark mopes on the raggedy edge of the paisley patterned couch. Like a shot, director Jacques Levy stops the microcosmic action, huddles with Boopsie, eyeballs composer Elizabeth Swados, nods a cue. The piano tinkles and the scintillating production number, “Another Memorable Meal,” shakes the floor boards of the downtown Manhattan rehearsal hall. “Doonesbury” is back in living color Garry B. Trudeau has invaded Broadway.

For those sixty-five-million-plus fans who went cold turkey last January 2 when Trudeau—amid much ado—dropped out with his syndicated comic strip, there is hope in the wings of the Biltmore Theatre. The four-panel strip has been blown up to a full-scale musical, melding the collective genius of the thirty-fouryear-old

Trudeau—marking his debut as a lyricist—and composer Swados (thirty-two), the Bob Dylan-ish bard of off-Broadway What began as a bare-bones workshop last spring has song-and-danced into a $2 millionproduction, starring Laura Dean (Boopsie), Kate Burton (J.J.), Albert Macklin (Zonker), Ralph Bruneau (Mike), Reathel Bean (Roland), Gary Beach (Duke), Keith Szarabajka (B.D.), Barbara Andres (Joanie), Mark Linn Baker (Mark), and Lauren Tom (Honey). Produced by James Walsh in association with Universal Pictures, the musical has a tune-up engagement in Boston prior to its opening on the Great White Way, November 21.

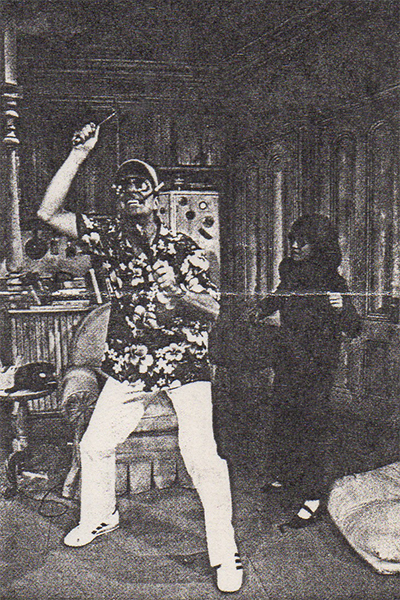

Zonker’s Uncle Duke and his sidekick Honey

Comic strips have been transformed into the stage and screen from “Blondie” in the late thirties to the recent Hollywood version of “Popeye,” directed by Robert Altman. Of course, “Little Orphan Annie” became the gold mine Annie of Broadway You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown and its sequel, Snoopy scored well in off-Broadway reviews. Even superheroes like Batman and Superman were recruited from the pancake-flat panels of the comic strips for missions in other entertainment

media.

Doonesbury, though, is puckishly different. It harbors a contemporary political wallop, backlit with satire. Trudeau writes dialogue that simultaneously tickles and bruises ribs. What Broadway musical would dare joke—in the mellifluous tones of television newsman Roland Burton Hedley, Jr.—that his Lebanese “techy” is alsodressinghair for the Phalangistsin Beirut? The one-liner triples with Hasahn’s twelve-hundred-watt hairblower beingmistaken for an Uzi submachinegun. Producer James Walshsaid,”This is a book show, I never even thought of itasa takeoff on a comic strip. I was personally drawn to the contemporary aspect of it.m Trudeau is a natural dialogue writer and he knows how to be funny CharlesSchulz, speaking of You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown, never got involved in the

writing end of that revue. I didn’t know`Doonesbury’ [the strip] from the man in the moon.”

Real life stings the wombish cocoon of Walden with Zonker’s Uncle Duke standing trial for smuggling ten kilos of cocaine for recreational use at American diplomatic missions. Duke, resplendent in mirrored aviator glasses, spit-and-polished combat boots, fatigue chinos, cigarette ‘holder, and baseballbilled nylon cap, belts out, “I’m just a man who’s been misunderstood” to a sneeringly skeptical jury Duke’s fetching aide-de-camp, Honey, comforts her ad-libbing boss with a Neroish, thumbs-down gesture.

“Doonesbury” creator Garry Trudeau with composer for the musical, Elizabeth Swados.

Director Jacques Levy, bookended with commercial and avant-garde theater successes from Oh! Calcutta to America Hurrah, talked about the collaborative thread between writer, composer choreographer (Margo Sappington), and director, that has sewn this production into a doozy of a musical. “It would be very difficult for you to go through this book and find anything in the show that didn’t have some spin-off by one or the other of us—no matter whose idea it was originally You lose the sense of credit altogether,” said the bearded and burly Levy as he puffed on a Lucky Strike.

“Garry has learned in a remarkably short amount of time how quickly a theater audience can understand what you’re getting at. He also is a very nervy guy so when ideas come up that might seem totally off-the-wall, he is not afraid to take a shot atthem. We set up a working system from the start. Garry and I would talk about whatitwas we wanted to accomplish in a particular scene. He would go off and write it, comebackto me with it, the two of us would work on it together in a kind of editing process, then he’d go back and do it again and then comebacktill weallfelt good about it. The same thing would happen with Liz. She would be on it all the way through. All of this happened, of course, before we’d try it out with the actors. Once we tried itout with them, there’d be more changes.”

Left to right: The cast that brings the animated characters to life in the Broadway musical, Doonesbury—Roland, Mike, B.D., Zonker, Mark, and Boopsie, played respectively by Reathel Bean, Ralph

Bruneau, Keith Szarabajka, Albert Macklin, Mark Linn Baker, and Laura Dean

Levy briefly described this creative marathon in situ:”If you can imagine Bertolt Brecht married to pop art, that is the closest way to describe the style in which I’m approaching this.” As Levy spoke, Liz Swados parried over yellow score sheets with the show’s musical director,Jeff Waxman, and the piano played backthe exchange in toe tapping transcription. A coffee klatch of actors slumped around along table, consulting oversize paperback copies of a “Doonesbury” anthology (Trudeau—via Holt, Rinehart, and Winston—has published twenty-four “Doonesbury” books and three anthologies)

as if they were the I Ching.

To flesh out the episodic and boxed-in adventures of the “Doonesbury” strip for the stage, the actors remain in view even when they’re not in scenes, weaving in and out of the action so the audience views them from two perspectives—delivering lines, dancing, and singing, and themselves watching the play unfold, limbering up for the next entrance. That is the Brechtian influence Levy has sculpted.

Close attention has been paid to the two audienceswhich stream to Doonesbury: the addicts, the ones who have followed the cloisteredshenanigans of the strip through its twelve-year tenure (Trudeaustarted his strip— which wasthen called”Bull-Tails” —at the Yale Daily News before it burst nationwide as a Universal Press Syndicate darling in 1970, and those who read the comic less pages of the New York Times. Both camps will find historical footing and comprehension in the characters. With “Doonesbury” in limbo from 725 daily newspapers, pressure mounts for Trudeau to come out of hibernation and restart his adorable crew in post-graduate climes. Perhaps he is taking Zonker’s cue when cornered with a careerquestion,”I’ve gottogo out and turn the compost heap.”