Willem de Kooning, left, and his daughter Lisa at the National Gallery in 1982 with E.A. Carmean Jr., then museum curator of 20th Century Art. photo credit: Craig Herndon

Willem de Kooning, the 85-year-old abstract expressionist painter lionized by some as the world’s greatest living artist, is the subject of a court petition filed in New York State Supreme Court by his only child and designated heir, Lisa de Kooning, and his lawyer of long standing, John L. Eastman, to declare him incapable of managing his own affairs “by reason of advanced age and mental weakness.”

While the petition states that the artist’s career “is still evolving” and that he “continues to paint daily and masterfully,” the accompanying physician’s affidavit filed by neurologist Frederick Mortati says that “in the absence of other evidence to the contrary … Mr. de Kooning suffers from Alzheimer’s disease.”

If the petitioners are successful, and that will be determined in a court hearing in Mineola, N.Y., on Aug. 18, they will have control of real estate, stocks and cash valued at $8 million and an as yet uninventoried cache of warehoused art-perhaps as many as 300 works-valued from $50 million to $300 million, depending on whose expert advice you accept. The low-end projection has been provided by de Kooning’s court-appointed guardian; the high figure represents the sweet equation of $1 million per artwork that some dealers suggest they could bring.

Since de Kooning’s longtime dealer, Xavier Fourcade, died of AIDS in 1987, no one has represented or sold the artist’s recent work. Only paintings dispatched by collectors or dealers at auction or private backroom sales have been on the market. Vintage de Koonings have consistently sold at auction for well over $1 million, including his 1944 “Pink Lady,” which fetched a record $3.96 million in May 1987 at Sotheby’s. The last late de Kooning, “Untitled V”(1981), sold for $385,000 during Fourcade’s single-owner estate sale at Sotheby’s in November 1987.

Mortati said a court appearance would be “detrimental to {de Kooning’s} physical and mental well being and, in any event, would be purposeless.” The artist is not expected to appear at the hearing.

The petition was filed last February, a scant 10 days after de Kooning’s wife, Elaine, also a painter, died of lung cancer at age 70, and its existence was revealed by Artnews magazine. Elaine de Kooning had managed her husband’s day-to-day business affairs after Fourcade’s death and had yet to make a determination of who-among a gaggle of high-powered dealers-would represent her husband in the international art arena.

Lisa de Kooning, 33, an animal-rights advocate and amateur sculptor, is the offspring of Joan Ward, who lived near de Kooning in the Hamptons in a house provided by the painter. They never married. Bill and Elaine separated in 1956-the year of Lisa’s birth-but reconciled in the late 1970s, some say just in time to save Bill de Kooning from drinking himself to death.

“Bill was always very clear that he would leave everything to Lisa,” said art critic Rose Slivka, who describes herself as a “passionate” friend of both painters. “Nobody expected Elaine to predecease Bill.”

According to a 34-page report compiled by Pierre G. Lundberg, the court-appointed temporary guardian of the painter, Lisa de Kooning receives approximately $300,000 a year from her father (broken down into a monthly $20,000 salary “for representing her father at various art functions” and $5,000 as a monthly gift), plus the taxes to cover the mega-allowance, another $75,000 or so.

To get a grip on what is at stake, Willem de Kooning’s net income in 1988 came to $1.8 million while his 1987 earnings were an astronomical $9.3 million, reflecting the frenzied salesmanship of Fourcade, who was in failing health, according to information Lundberg gleaned from John A. Silberman, Lisa de Kooning’s lawyer.

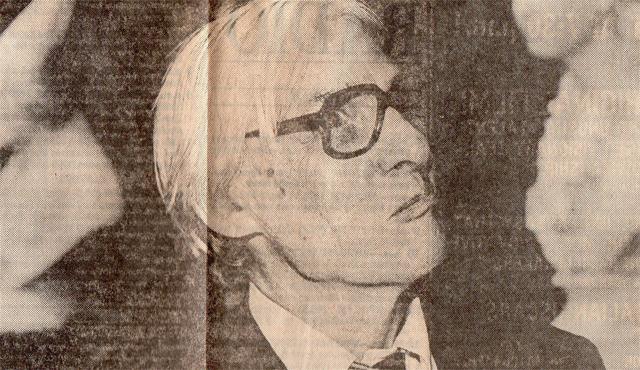

Willem de Kooning in 1982, photo credit: Craig Herndon

The Easel at Stake

Willem de Kooning’s annual payroll for studio staff (to stretch, frame, conserve and document his paintings) and around-the-clock nursing care comes to $447,000. His investment income runs between $500,000 and $550,000 a year. As Lundberg opines in his investigation, “Mr. de Kooning’s present expenses … appear to exceed his investment income. If this is so, support and maintenance for Lisa must come from the sale of works of art or from capital … there is a need for the appointment of a conservator without further delay.”

Lundberg recommended to the court last month that Lisa de Kooning’s payments be cut to $13,000 a month or $156,000 a year, noting, “Lisa is not disabled.” He also recommended that John Eastman be appointed “… sole conservator, or jointly with Lisa.” Eastman is a major entertainment lawyer whose father and partner, Lee, was de Kooning’s lawyer, beginning in the ’50s until his son gradually took over. He also was a major collector of the artist’s work. The younger Eastman also represents singer Paul McCartney, the ex-Beatle and husband of Linda McCartney, Eastman’s sister.

Although the petition didn’t ask for this opinion, Lundberg nevertheless stated, “… I cannot recommend that Lisa ever serve as sole conservator.”

Part of Lundberg’s cautionary note stems from a potential conflict of interest in a series of loans amounting to $342,000 from 1981 to 1986 listed in the elderly de Kooning’s financial records as having been made to Lisa. The money was used principally to build a home for Lisa on property adjacent to her father’s acreage on Woodbine Drive in East Hampton. But also covered were “travel and other expenses.” The land was a gift from her father, now appraised at $21,000.

Lisa’s lawyer, John Silberman, says the loan is a simple bookkeeping error due to the bookkeeper’s new computer software that had a place for loans but lacked one for “gifts.” “It’s as silly as that,” said Silberman in a phone interview. “As far as I know there was no intention for Mr. de Kooning to be paid those monies back.”

Back in 1985, Lisa de Kooning found herself the subject of a New York Post headline, “Heiress linked to Hell’s Angels.” The brief item carried a photograph of a barefoot and smiling Lisa playing with a huge dog “in happier days.” According to the tabloid, FBI agents tapped her phone and searched her SoHo apartment seeking evidence in their Hell’s Angels’ drug racketeering probe, dubbed “Operation Rough Rider.” “The young, high-living heiress” was linked to the notorious motorcycle gang in court papers, reported the Post. Although 125 people were arrested in the nationwide drug bust, Lisa de Kooning was never charged with any wrongdoing.

“That’s her past, and now she’s a devoted mother, wife, daughter and artist,” responded attorney Silberman in a phone interview. “She did lead a rather free-flowing and unconventional past, being the daughter of an artist, but that’s all behind her. It has nothing to do with her present life.” Lisa de Kooning was not available for comment, according to Silberman, “at least until the court proceedings are over.”

Lundberg did not delve into Lisa’s past in his report but noted that “there were no visible signs of lavish living or extraordinary expenditures” when he interviewed Lisa in her “very nice but smaller house a stone’s throw away” from her father’s. Lisa’s husband, Cristian Villeneuve, a landscaping contractor, and their 2-year-old daughter, Isabelle, were in Canada, visiting relatives at the time. In the court papers, the attorney described Lisa’s responses to his questions on what the $300,000 yearly allowance was used for as “vague or inconsistent.”

The Rothko Parallel?

A number of observers close to the family brought up the analogy of another great artist with a huge trove of paintings. “People are really looking for the Rothko case all over again,” commented one adviser close to Lisa, “and it’s not there so they’re making things up.” Painter Mark Rothko committed suicide in 1970, leaving behind 800 paintings and a resultant lawsuit over his estate that ultimately cost his three executors and dealer, Marlborough Gallery, $9.2 million in fines.

Although a dealer will not be chosen until the August court date, Arnold Glimcher, president of Pace Gallery, is the front-runner to represent de Kooning. Pace already has an extraordinary stable of both living and dead artists, from Julian Schnabel and Richard Serra to the estates of Pablo Picasso, Isamu Noguchi, Louise Nevelson and Rothko. (Pace was authorized to act as Rothko’s worldwide agent in 1978, a considerable coup and possible precedent.) Glimcher did not return telephone requests for an interview but a spokesperson at the gallery said, “He has nothing to say.”

During Lundberg’s interview with the 51-year-old art dealer and film producer (“Legal Eagles” and “Gorillas in the Mist”), Glimcher said that the recent paintings he had viewed at de Kooning’s studio were “among the best de Kooning work he had ever seen” and estimated he could sell them to an international clientele for $500,000 to $1 million apiece. Glimcher told Lundberg that in order to sell 10 paintings he would need access to 30. It is estimated that de Kooning has painted at least 70 pictures since Fourcade died and has consistently kept paintings off the market, squirreled away in his museum-quality storage facility on his property.

“If he goes with Pace, they’re great merchants in the sense that they can sell anything,” said Allan Stone, a maverick dealer and major de Kooning collector. Stone purchased de Kooning’s 1954 masterpiece “Two Women” for $1.2 million at Christie’s in 1983-at the time a record for a piece of contemporary art bought at auction.

“It doesn’t matter how good or bad it is,” said Stone, who put on six de Kooning exhibitions between 1962 and 1972. “I have problems with the late work myself, and I even told Elaine that I thought about 80 percent of it should be suppressed and the best 20 percent dealt with. I think his work now is an echo of what it was, but on the other hand, people thought that way about Monet. Whoever winds up getting it will probably make a fortune.”

Stone also said that up until the 1970s de Kooning was not a prolific painter but “he was encouraged by his lawyer {Lee Eastman} to churn out work, so he did. So he’s produced a rather large body of work in the last 15 years, more than he produced in the early part of his career. And they’ll all be worth money to some people. The people coming into the market today understand a de Kooning to be a great big red, white and blue or red, yellow and blue splashy picture.” Stone compared the current frenzy of interest in de Kooning to the last months of Franz Kline’s life, when “an awful lot of Klines were sold, and that’s why there was never much of a Kline estate.”

How hungry is the de Kooning market? “He’s a great property and people will want to have his pictures,” says Martha Baer, director of Christie’s New York 20th century fine arts department. “He is the last grand figure that’s still alive from that generation’s famous artists: Pollock, Kline and Rothko. I think he has to be protected, but frankly I don’t think they should choose a dealer at this point. They should leave him alone.”

“I’m very high on de Kooning’s work of the 1980s,” said Jeffrey Deitch in a phone interview from London. Deitch is an art adviser who purchased Jackson Pollock’s “No. 8, 1950” for a record $11.55 million last May at Sotheby’s for an anonymous client. “There are a lot of people-myself included-who feel that the very late work is among the best work he’s ever done. The pictures will speak for themselves. … There was a reluctance at first about the late work, that it was repetitive, but I think that was a premature judgment on the part of the art world.”

Asked if there was any credence to the theory that the de Kooning market was in a slump because no new pictures are coming on the market (a view held by John Eastman), Deitch responded, “There is a tremendous demand for it. Right now there is remarkably little of the late work for sale. I’ve been trying to buy one all year. I finally found one of superb quality that was on the market. The dealers who have good paintings are holding on to them for very substantial prices.” Deitch said that $1.5 million is the current price for a top-quality ’70s piece, and “approaching a million” for a similar-quality ’80s painting. “You can make an analogy with late Picasso. There were very few true believers.”

De Kooning’s late work met with market opposition when Fourcade was representing him at his East 75th Street salon, and de Kooning exhibitions-there were eight solo shows between 1975 and 1985-were not sellouts. “Ten years ago, art didn’t get gobbled up like it does today,” said Jill Weinberg, the longtime associate director of Fourcade and now a partner with Bernard Lennon in a SoHo gallery. “Xavier always used to say there was a `lagging behind’ of five to 10 years in the acceptance of de Koonings. Xavier was always interested in exhibiting the most recent work.”

According to a number of savvy observers, it was a frequent practice of Fourcade (who facilitated the sale of Barnett Newman’s “Stations of the Cross” to the National Gallery) to heavily discount de Koonings so a $250,000 price tag could be slashed to $175,000. But that ended when Fourcade died.

The Artist and the Dealer

It was Fourcade’s unique relationship with the increasingly recalcitrant and withdrawn artist that got de Kooning grudgingly to sign his paintings on their stretcher bars and only just before they left the studio. In the last couple of years, according to Rob Chapman, de Kooning’s longtime studio assistant, that practice has become inconsistent.

“Bill hasn’t signed his name to works in the last few years,” says painter Conrad Fried, Elaine de Kooning’s younger brother and longtime ally of the duo. “A few years ago he told me, `If they don’t like it’ and {then he} made a loud noise blowing through his lips. When he was young he had money troubles but now it doesn’t make any difference.”

The irony between the anxiousness of his proposed conservators to exhibit and market his recent work (de Kooning has not shown in New York since two of his 1986 paintings were included in the 1987 Whitney Biennial) and the apparent obstinacy of the artist about letting his art out of his studio is clearly expressed by de Kooning’s old friend, the abstract painter Herman Cherry: “It’s like telling Picasso he’s got to get a gallery.”

Fried puts it differently: “De Kooning doesn’t care about selling and doesn’t care about showing. He’s painting and that’s all he cares about. This talk of him owing it to his public to show his work is bunk. They want to take away his own name.”

Lundberg, after a visit to de Kooning’s home in March, had this chilling description of the painter’s behavior: “When I tried to ask him questions, {he} would utter a response which would be unintelligible to me. I could elicit no direct or meaningful response to any question I asked.” And Cherry said, “He doesn’t recognize his friends. He doesn’t recognize me. The way I’d put it, he’s withdrawn into himself. He’s working all the time inside of himself and it shows in the paintings.”

Asked about Lundberg’s comments, Fried said, “Bill is a very egotistical man and wants to talk about what he wants to talk about. It’s partly a matter of choice and a lack of interest, part of being surrounded by people who are not interested in the things he is. Lots of rich people don’t handle their affairs or walk around with their checkbooks in their back pocket. I don’t believe the Alzheimer’s story.”

Fried visited de Kooning at his studio earlier this summer and described the work he saw there as “marvelous.” “He has a style now that’s really very good … sweeping curves and blended colors that appear both simplistic and very rich. He didn’t get stuck with one style like Pollock did. He has periods just like Picasso.”

“It’s very exciting to watch him paint,” says art critic Slivka, who recently visited de Kooning’s studio. “As always, he brings his whole body into it … it seems to flow out of his fingers, his way of touching the canvas as if he were following the color lines, as if he’s feeling into a very deep part of his life.”

A Question That Transcends Medicine

Asked if de Kooning knew about Elaine’s death (he did not attend her funeral), Slivka said, “I think Bill can afford to know what he wants to know. That’s really having made it in life, where you can absolutely block out what you don’t want to know. I think he chose to not take that in. I certainly didn’t want to.”

“It hurts me very much that I can’t talk to him anymore about anything,” says sculptor Ibram Lassaw, a friend of de Kooning’s for more than 50 years. “He just doesn’t talk. I’m absolutely amazed he’s doing such good painting and yet they’re trying to say he’s incompetent. He may be, in practical matters. We used to sit around and talk about many things, mostly art or listen to music for hours, just sitting there quietly with Bach and Mozart. I don’t think he listens to music anymore.”

Is it possible for an artist suffering from Alzheimer’s disease or some other form of progressive dementia to paint masterpieces? “In neuropsychological terms, it is entirely possible … despite the loss of other functions,” says Barry Gurland, director of Columbia University’s Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology. Gurland described this phenomenon as “an island of performance” and used an example of a diplomat suffering from dementia who could still behave in an articulate and delicate manner. “It just comes as second nature for those who are overly trained.”

Gurland cautioned that “at the moment you can’t diagnose Alzheimer’s disease prior to death,” and when told of de Kooning’s history of alcoholism, he added that any diagnosis would be “very difficult.”

“It’s a question that transcends medicine,” retorted Dr. John Schaefer, a neurologist at the Cornell University Medical College, “but I doubt that he could be really producing top-flight art and be suffering from an advanced state of Alzheimer’s. Those observers who felt so strong about the work would be viewing it through rose-tinted spectacles.”

“If it’s Alzheimer’s, there will come a point when he will no longer be able to grasp a paintbrush,” said Dr. Barry Reisberg, clinical director of the Aging and Dementia Research Center at New York University Medical Center. Told of the guardian’s report about de Kooning’s regimen (“still able to brush his teeth if handed a toothbrush”), Reisberg said, “If as you say, he no longer recognizes friends, it sounds as if he’s somewhere in the sixth stage of the disease. Later in this stage speech ability becomes severely compromised and eventually lost. … The final stage is the seventh.”

Reisberg cautioned that other factors, such as medication, depression, toxins from paint, vitamin deficiencies from drinking or injury to the brain from falls can cause memory impairment and some of these conditions can closely mimic Alzheimer’s. “We do not know the cause of the disease.”

There are many images of de Kooning to choose from in his larger-than-life career: posing handsomely in front of his snarling “Woman” painting in 1953, a rising star about to strike it rich. Or alone in his magnificent, skylit studio, surrounded by six large canvases, all still in progress. At this time it is difficult to separate the legend of America’s Picasso from that of a fallible hero, or worse, from that of an interesting psychological case study. Ultimately, as one observer says, “the paintings will speak for themselves.”