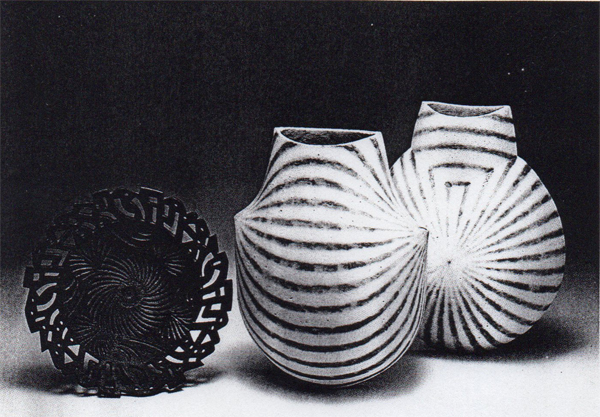

From L to R: Plate, Ian Godfrey, circa 1981. Stoneware; 9.5 inches in diameter. After years of public attention, Godfrey withdrew to the seclusion of his studio, where he continues to work in virtual isolation, executing works that often reveal his fascination with the symbolic forms and imagery.

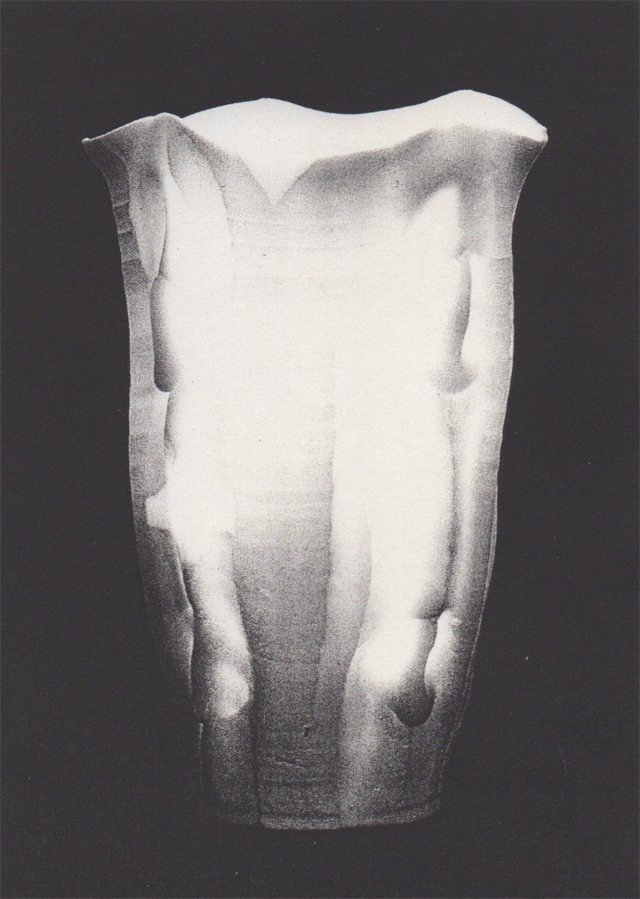

Vase, John Ward, 1989; stoneware 12 inches high. Vase, John Ward, 1990. Stoneware; 12 inches high. Ward, like Ian Godfrey, studied at the Camberwell School of Art under Hans Coper and Lucie Rie, whose influence can be seen in these restrained tension of these two vases. Images courtesy Graham Gallery.

The market for contemporary ceramics, long a stepchild of the fine arts, has emerged in 1990 alive and kicking. England and the United States—particularly London, New York and San Francisco—are the major centers, fueled in part by a recent influx of collecting interest from the Japanese, a culture accustomed to the glory of the handcrafted vessel.

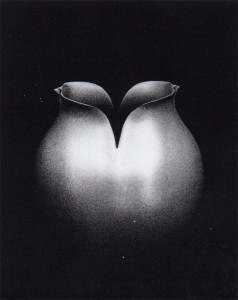

Vase, Kawase Shinobu, 1989. Porcelain 10.5 inches high. Kawase’s vase, as if sublime homage to the purity of form, exemplifies his skill in perfecting the celadon glaze that he is known for. Image courtesy Queensberry-Pilscheur, London.

It should be noted that some experts insist that a distinction must be made between “vessel” and “sculpture” artists working in ceramics. “The market in England is still very much dominated by what I would term the vessel makers,” observes David Queensberry, a major voice in the development of contemporary English ceramics and a former professor at the Royal College of Art in London. “Collectors in England tend to like things that have an umbilical cord to what one might call the ceramics tradition,” he says, “even though they’re not really buying a vase to put flowers in.”

To illustrate his point, Queens-berry explains that William Staite Murray—an early modernist who exhibited his pots at the prestigious Lefevre Gallery in London during the 1920s and 1930s and who was part of the artistic circle that included Vanessa Bell, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson—”would give a pot a poetic name.” Bernard Leach (1887-1979), perhaps the most famous name in modern English ceramics, credited with reviving the tradition of hand-thrown pottery, “would simply call it ‘milk jug.’ ”

The mold that has confined clay artists, in the museum world and the marketplace, is breaking

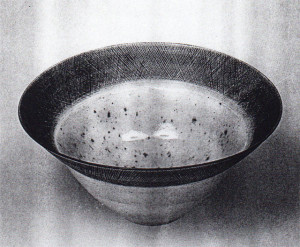

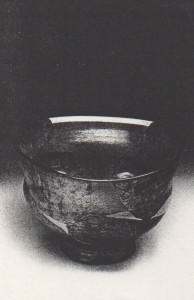

Bowl, Lucie Rie, circa 1960. Porcelain; 9.5 in diameter. One of Britian’s potters, the Vienna-born Rie moved to London in 1938, where she exerted an influence on the postwar generation of ceramists. Sgrafitto rims and monochrome glazes characterize many of her bowls. Image courtesy Galerie Besson, London

Queensberry rates the “post-Leach people” like Lucy Rie and Hans Coper (1920-1981) (Rie emigrated to England from Vienna and Coper be-came her assistant in 1946) higher than those of the “Anglo-Oriental tradition” proselytized by Leach and his protege, Michael Cardew (1901-1983). Recent auction prices for works by Rie and Coper buttress Queens-berry’s assessment.

At Bonhams’ contemporary ceram-ics sale last February, an early “bottle form,” circa 1956, by Hans Coper sold for $23,700, doubling the high end of its presale estimate. A “shiny white stoneware vase” by Lucy Rie from circa 1960 sold for $11,000 in the same sale, easily exceeding its presale estimate. A late stoneware vase by Bernard Leach with his signature black-and-rust temmoku glaze, circa 1970, snared $7,600, slightly above its high estimate. Works by lesser-known but highly regarded ce-ramists brought more modest prices.

Teapot, Beatrice Wood, 1990. Earthenware; 13 inches high. Wood’s interest in ceramics was inspired in 1933 by here desire to matching teapot for a set of luster plates shes has purchased. Over the decades, the teapot has become a favorite vehicle for her singular vision. Image courtesy Garth Clark Gallery, New York.

Vessels by Coper, Rie, John Ward, Ian Godfrey and other ranking English ceramists are regularly exhibited in New York at the Graham Gallery. “The line between craft and art has really almost vanished,” says Terry Davis, who initiated Graham’s involvement with the medium in 1977.

Recent exhibitions in prominent New York galleries better known for showing the latest in painting and sculpture amplify Davis’s contention. Betty Woodman at Max Protetch, Elsa Rady at Holly Solomon, Stephen de Staebler at CDS, Viola Frey at Nancy Hoffman, John Gill at Grace Borge-nicht, Peter Voulkos at Charles Cowles, and Robert Arneson at Frumkin / Ad-ams are among the best examples. The mold that for so long has con-fined clay artists, both in the museum world and in the marketplace, is at a breaking point.

The crossover phenomenon is less visible in England, with the rare ex-ception of the prestigious Anthony D’Offay Gallery, which recently took on the work of Andrew Lord, who shows in Los Angeles at the Margo Leavin Gallery. “There’s still a prob-lem about positioning ceramics in re-lation to the fine arts here,” says London art consultant and collector John Huntingford.

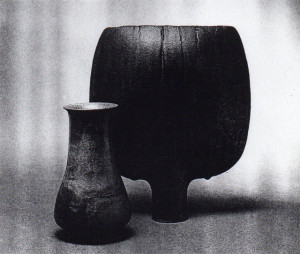

Vase, Otto and Gertrud Natzler, 1962, Ceramic, 6.5 inches high. Open Disk Form, Otto Natzler, 1984, Ceramic; 11 inches high. Renowned for their technological expertise, the Natzlers began an artistic collaboration in the early 1930’s that continued until Gertrud’s death in 1971. Gertrud would throw the clay while Otto, “the mater of glaze,” refined the color and texture of each surface. Five years after Gertrud’s death, Otto resumed work, creating a more sculptural type of vessel. Images courtesy Newman galleries, Beverly Hills.

Representing another front is vet-eran dealer Helen Drutt. With galler-ies in New York and Philadelphia, Drutt offers a strong array of Ameri-can ceramics, from the translucent porcelains of Rudolf Staffel to the wildly kitschy yet postmodern sculp-tures of Mark Burns. “I’d rather hear the question, ‘Are they collecting good art?’ than ‘Are they collecting clay?’ ” says Drutt.

In a similar vein, Garth Clark, a for-mer student of David Queensberry, has become a major dealer in ceramic art on both coasts. He focuses on American work, from the minimal beauty of Ruth Duckworth to the lustrous excesses of the incomparable Beatrice Wood. Clark is also a prolific author on the subject of ceramics, with fourteen titles to his credit. “What’s different about this field,” says Clark, “is that most of the better artists—even at current levels—are underpriced compared with other ar-eas in the market. So you can come into the field under ten thousand dol-lars and buy real masterpieces.”

In his encyclopedic volume Ameri-can Ceramics: 1 876 to the Present, Clark identifies the roots of the art pottery movement in the Rookwood Pottery in Cincinnati, which began in 1878. From the elegantly restrained salt-glaze stoneware of Milwaukee-bred Susan Frackelton (1848-1932) to the precociously surreal concoctions of George “the mad potter” Ohr (1857-1918), American ceramics began to find its voice.

Up until the close of World War II, with a few eccentric exceptions, European influences prevailed. Artists better known for their sculptures—such as Elie Nadelman, Isamu Nogu-chi and Louise Nevelson—were mak-ing great strides in clay. By the 1950s the notion of “hygienic hotelware” (artist-critic Henry Varnum Poor’s wonderful phrase) was banished, and California emerged as the capital of ceramic art. Works by new talents such as Gertrud and Otto Natzler dazzled critics and curators with their extraordinary glazes and classi-cal aesthetic, eventually entering the collections of many American muse-ums. And in the early 1960s, California produced a vintage of potter-art-ists dominated by the all-consum-ing visions of Peter Voulkos and Robert Arneson.

Bowl, Wayne Higby, 1988, Earthenware; 14 inches in diameter. “Concerned with Landscape imagery as a focal point of imaginary vision as representation of a particular location,” Higby Strives to to create a “a zone of quiet coherence…where finite and infinite and immense intersect.” Image courtesy Helen Drutt Gallery, New York

Garth Clark sees a new group of emerging collectors who also buy “quite aggressively” in painting and sculpture. A top ceramics artist such as Peter Voulkos (represented by the Charles Cowles Gallery in New York and the Braunstein /Quay Gallery in San Francisco) commands as much as $80,000 on the resale market and is racing toward six figures. But Clark says, “We still don’t have anything approaching a parity with fine art prices and probably never will.”

There are exceptions. At Sotheby’s London last October, Joan Miro’s Personnages, a hand-painted and par-tially glazed earthenware plaque, circa 1954, sold for $206,000 to a pri-vate Portuguese collector. It was a world record for any ceramic by a twentieth-century artist. Obviously, Miro’s standing in the pantheon of great modern artists contributed mightily to the price.

Robert Arneson is considered one of Voulkos’s closest American coun-terparts, though he represents the fig-urative side of the funky northern California aesthetic. He has been de-scribed by one dealer as “the Claes Oldenburg of the medium” because of his rule-breaking approach to ceramic sculpture. Prices for Arneson’s politically charged work range from $9,000 to $100,000. “Arneson crossed the bridge,” says an admiring Charles Cowles. “He’s not just making pretty little teapots.”

Cowles points out that the com-bination of increasing demand for Voulkos’s work and recent auction results has pushed prices for current work to new levels. When Voulkos shows in October at the Braunstein/ Quay Gallery, the “stacks” that in March wore price tags of $35,000 at Cowles could jump as high as $45,000.

“The line between craft and art has almost vanished.”

Auction houses in London and New York have in many ways legitimized and expanded the market for contemporary ceramics. In part be-cause the gallery scene in London is less developed for ceramists than it is in the States (Galerie Besson and the Michaelson & Orient Gallery are impressive exceptions, with Besson rep-resenting the top rung of English potters such as Elizabeth Fritsch, and Michaelson & Orient handling younger, lesser-known ceramists such as Peter Simpson and Glenda Cahillane), Christie’s London and Bonhams have stepped in to fill the void, selling work fresh from artists’ studios.

Instead of paying dealer commissions, often pegged at 50 percent, artists, like other consignors, pay the auction house as much as a 10 percent fee. This practice does not sit well with everyone, however. “I see it as somewhat destructive to the whole scene,” says David Queensberry. “It makes opening a gallery almost impossible. What happens if a piece sells at auction for four hundred dollars when it was valued at two thousand dollars? Prices collapse and that per-son’s market is destroyed.”

Vase, Rudolf Staffel, 1989. Porcelain, 8 inches high. In the translucent porcelains called “light gatherers,” Staffel takes the vessel form beyond function and decoration and imbues it with an expressive, ethereal quality. Image courtesy Helen Drutt Gallery, New York

Cyril Frankel, the moving force be-hind this trend—first at Christie’s and currently at Bonhams—counters, “We’ve had a certain amount of criticism from one or two galleries saying, ‘It’s our job, not yours.’ But there aren’t enough galleries to show this whole school of newcomers. It’s simply an outlet for artists.”

The controversial practice of selling work fresh from artist’s studios at auction is unlikely to reach the United States. “I had to make peace with the dealers and assure them we would sell only ‘secondhand,’ ” says Kathleen Guzman, president of Christie’s East and the force behind Christie’s American entry into the field. “We would not be in direct competition. I saw there was a need to make a secondary market, and the dealers were receptive.”

In an auspicious single-owner sale marking its New York debut in February 1989, Christie’s auctioned sixty-five objects from the ceramics collection of St. Louis lawyer Earl Millard. Only five lots went unsold, and the collection realized $236,000. At Christie’s second sale in New York last February, sixty-eight of the nine-ty lots offered brought $374,500. Sotheby’s has yet to enter the American contemporary ceramics market.

Sotheby’s London has applied the brakes on selling work fresh from artist’s studios, according to David Battie, now a Sotheby’s director, who started the trend at the Belgravia salesroom in 1978. “There are not an awful lot of people out there buying modern works of art,” says Battie. “Paintings, yes, but not three-dimensional things and different media. You’re not selling works with a track record but selling art hot out of the kiln or whatever it happens to be. It’s incredibly difficult. Artists commanding serious money are few and far between.”

Auction houses have in many ways expanded the market for contemporary ceramics.

In the ceramic art arena, name recognition continues to account for a significant market share. Just a hand-ful of living artists in England and the United States are responsible for making recent waves. With its robust gallery network, the United States is a stronger market for ceramic art than England. But no matter what country you collect in, “people will pay infinitely more for a two-dimensional object,” says Battie.

His cogent remark, “If you can hang it on the wall, it’s worth a lot more than if you can stand it on the sideboard,” captures the mysterious prejudice still held against the medium. Fortunately, this same bias creates a timely opportunity to collect an undervalued art form.