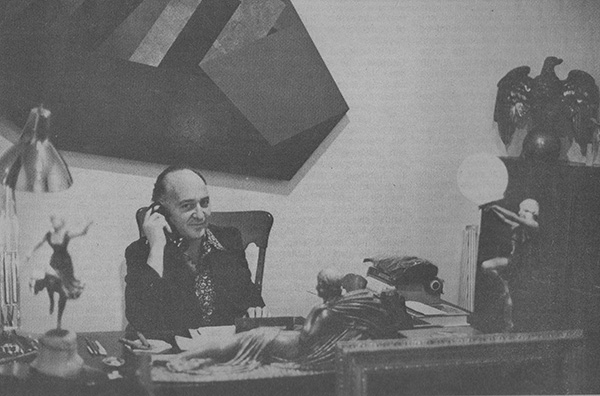

Ivan Karp. Photo by Sarah Wells

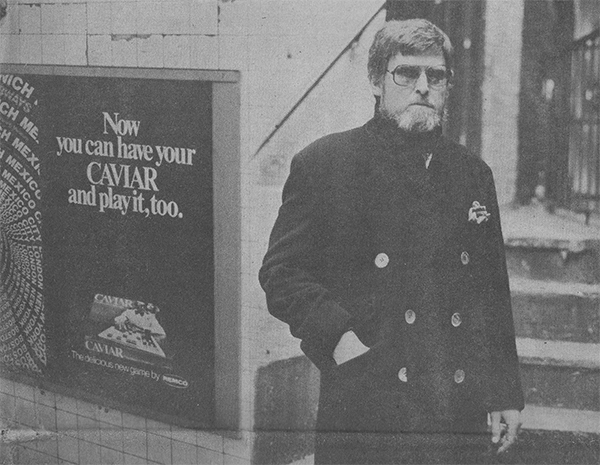

In a grungy stairwell of a BMT subway station on 23rd Street a poster-sized ad extols, “Now you can have your caviar and play it too.” This “delicious” new game by Remco is conveniently called “Caviar.” In other parts of town another game is being played without the Remco trademark. In this game, the caviar eats some of the players (artists and dealers) who lose paintings, prints and drawings to the game’s creator, Irving Newman.

Newman barters fish for art—at least that’s the version hyped in recent articles in the Daily News, New York Times, and Art Gallery, “the international magazine of art and culture.” An investigation by this newspaper, however, has uncovered some startling fish stories which deflate the puffy character of Newman.

Philipp J. Weichberger, a New York artist, was visited by Newman several years ago. The artist swapped several paintings for a like amount of caviar, pickled herring, and salmon. The paint-ings were removed from the studio on the promise of delivering the fish the next day. Weichberger was planning a party and the notion of serving caviar to his guests was most palatable. Newman never delivered the fish, and the artist never got his paintings back.

In a document made available to this newspaper, which Weichberger titled “Worst Baits,” the artist observed (in the third person), “The undersigned has, from time to time, traded paintings against services. This is the first time he has been defrauded. There is in-my opinion nothing as despicable as a man, who under the guise of a humane merchant baits artists, with fish no less, into giving him paintings and receiving nothing in return. If there are already two artists in the same neighborhood (William G. Anthony, P.W.’s neighbor) that have been defrauded by this man, the law of averages dictates, in my opinion, that there must be dozens of other artists out there, that have been taken by him, too. In the future,” Weichberger concludes, “nobody should fall for this man’s bait.”

Philipp J. Weichberger, photo by Sarah Wells

Weichberger’s law of averages theory netted a smorgasbord of artists and dealers who claim to have been filleted by Newman. Gallery owners on Madison Avenue and West Broadway; artists on the Bowery, Union Square, Soho and Tribeca, and even a gourmet food shop owner on Prince Street bristled (like a Brisling Sardine) at the magic name—Newman! The local office of the FBI, the Stolen Property Squad of the New York PD, Small Claims Court, the Criminal Court of the City of New York and the Association of American Art Dealers, Inc., all have, by hook and crook, dealt with the man who the Daily News nick-named, “the Fisherman.”

KARP’S TALE

Ivan Karp (the bouillabaisse thickens), the legendary ruler of OK Harris Gallery on West Broadway, immediately tore into Newman’s image as art swapper extraordinaire—”He’s a criminal, he’s got to be stopped.” Karp painted a sleazy picture of Newman poking around the racks and crannies of the gallery in 1973; showing up on the busiest day, Saturday; making lots of phone calls, describing himself as an international art dealer and early American antique collector with a fish import business out of Iceland. “For us to be naive is ridiculous. It’s rather shocking, but he is an unfamiliar type to the art community.” Karp took for granted that artists are naive. In a wave of confusion, gallery workers turned over eight drawings valued at $3,500 to Newman with-out getting paid for them. Karp pointed out that 50-60 percent of art gallery business is transacted this way—the “buyer” gets the goods and the gallery gets the cash at a later date. In this case, Newman was to have paid for the drawings on the spot.

GALLERY ROE

During the same period, Karp was called by his next door neighbor, James Yu of the James Yu Gallery, and questioned about one Irving Newman who wanted to trade caviar for paintings. This was before Karp had gotten hooked, so Yu went ahead and exchanged $12,000 in paintings and drawings with Newman.

Nancy Hoffman Gallery, another elite spa for new art on West Broadway, was visited by Newman on numerous occasions—with similar descriptions of him making endless phone calls and asking endless questions. Later on, a phone company inquiry about the source of a credit card number aroused the dealer’s suspicions of the eccentrically disheveled Newman.

James Yu, unable to reach Newman began to collect information from artists and dealers who had been hit by the Ice-landic angler. When his file began to bulge with affidavits, he contacted the Manhattan DA’s office and warrants were secured to enter and search New-man’s lower East Side co-op apartment.

Detective Lucretia Belardo of the Stolen Property Squad of the New York

PD visited Newman’s apartment at 77 Columbia Street, armed with a list of paintings and drawings alleged to have been snared by the caviar encroacher. The apartment was crammed with art—a closet door stood ajar from the mass of framed and unframed canvases and prints. An inventory was taken and many of the works of art were removed.

Docket #N452959 from the Criminal Court of the City of New York under Judge Howard E Goldfluss, dated Feb. 21, 1975 states in part: “Evidence of his,” (Newman’s) “obviously false prom-ises, failure to respond to the varied correspondence from the complainant,” (Yu) “requesting payment or return, the admission by defendant to other similar transactions (which, though they are not charged in the complaint, they are admissable to support the inference that the act charged was not innocently or inadvertently committed), to a moral certainty, fraudulent intent has been proved. The defendant is guilty as charged.”

Judge Goldfluss fined Newman $1,000 or 90 days in jail. Although paying with cash was an alien experience, Newman opted for the bucks and didn’t pay the fine until April 25th of that year.

Charles R. Purcell lost two figurative paintings in the Newman shuffle: Chrisy / (79 x 59″) and Chrisy II (79 x 40″), both oils on canvas. Purcell, who describes himself as “not a big fish eater,” told Newman that he would trade for some fish and some cash. Newman agreed, took the two paintings and “delivered six quarts of overrated, dyed caviar.” “He skipped out,” Purcell said, “and never paid any cash. He shipped all the paintings to Iceland so they couldn’t be repossessed. It was a total loss. I felt 1 had no recourse since the government,” (meaning the City of New York Criminal Court) “just fined him $1,000—it wound up costing him less than what he owed me—$1,800. Newman took two very nice pieces. I could have sold them several times over. I would love to get those paintings back. This was very demoralizing to me. He put me through the wringer. If you find out where he is,” the artist wistfully spit out, “I’d love to put a burr in his cap.”

Jane Kaufman, an artist whose series of black velvet multi-media panels were recently exhibited at the Droll-Kolbert Gallery, responded in a neo-Pavlovian way when the name Irving Newman was dropped during a phone conversation, “I thought he was in jail.” Kaufnian con-sidered herself fortunate in dealing with Newman. She at least got a partial pay-ment in caviar—four to five pounds worth—for one painting. “He’s a very weird man,” (taking note that there are a lot of weird men around) “I just thought he was crazily lonely—a man who kinda liked artists. He didn’t strike me as someone who knew about art or wanted it. He wanted the human contact. No-body I know turned him down. He’s a pathetic character.

Nancy Grossman, another artist who felt the hook of Newman’s line, cautioned, “Put up your dukes when you see him coming.” She had to employ the persuasive threats of her dealer (who, through a spokesperson requested anonymity) to get her promised fish eggs.

BIG FISH

Two internationally established artists, Romare Bearden and Alice Neel, who coincidentally have some of their recipes (one, for a salmon mousse) published in the Museum of Modern Art’s Artists’ Cookbook, had nothing but praise for Newman. Alice Neel said she met Newman at the old cafeteria in the basement of Atran on 78th Street, just off Madison. “He’s smart and very nice. He has a good eye for art. I think he does it (trades) because he loves art. He never cheated me.” Ms. Neel joked about the great quantity of caviar she has eaten to the point of “being fed up on it,.” Romare Bearden doesn’t like caviar (its too salty for his taste) but feels it has the “open sesame” effect. Bearden seemed impressed by Newman’s art collection, especially some woodcuts by a Belgian artist. Before our phone conversation ended, Bearden chuckled into the receiver, “You get to meet lots of strange and interesting people in New York.”

CAVI ARTS

Philipp Weichberger, who paid an un-announced call to Newman’s apartment last December 4th with his colleague, Bill Anthony, found Newman in his bath-robe “surrounded by paintings, floor to ceiling” but was unable to locate his own work.

Harvey Quaytman, a constructivist who shows at the McKee Gallery, spot-ted Newman recently in the vestibule of his Bowery loft building with a neighbor, Tom Wesselman. According to Quaytman, Newman pretended that he didn’t recognize him at the chance en-counter in the vestibule. He later called his neighbor Wesselman to warn him of Newman’s strange techniques in acquiring art by hype. Three years ago, Quaytman swapped two of his geometrical drawings for some “Icelandic hand-made sweaters.” Newman never delivered the sweaters. The artist had to bluff his way into Newman’s apartment and after a struggle, physically removed his drawings.

Gertrude Stein (no relation to the one you’re thinking of), proprietress of Gallery: Gertrude Stein on Madison Avenue, traded a painting and a $400 check to Newman two and a half years ago for some coats he claimed to manufacture “in Alaska or somewhere.” Ms. Stein said, “He’s just an awful man. When I think back, I was so stupid, but he mentioned the right names and you don’t assume someone comes into the gallery as a thief. I’d serve him with papers but he’s so elusive.”

Margit Chanin, a private dealer, says she traded paintings with Newman for similar hot air. “He called me up and sounded fairly knowledgeable and knew about the art world. He was not stupid. He took quite a few pictures and never paid for them. I called the Art Dealers Association of America but they wouldn’t help me because I wasn’t a member. He’s still doing it. Two weeks ago, Newman tried to sell some of my paintings very cheap to a friend of mine but she recognized the work and knew they belonged to me. He gave me phony business cards, made a lot of calls from my apartment and ate up an enormous quantity of party food I was preparing in my kitchen. I never saw anything like it. He did it to all of us, up and down the line, but all we art dealers just take it. Some are too proud to admit they’ve been taken. I got disgusted and gave up. My lawyer who was working on the case died.”

Attempts to reach Newman to get a reaction to some of these fish stories proved almost futile. A letter written to his home requesting an interview netted one brief phone call. Newman told me to get the Daily News story and copy it. My first question about the Criminal Court suit exacerbated his staccato style of conversation and before slamming the phone down, he yelled at me, “Look buddy, if you know so much ….” That eardrum is still vibrating.

Paul Rotterdam, a Tribeca artist who has had extensive dealing with Newman claims he was on hand when Newman purchased caviar wholesale in the early morning hours at the Fulton Fish Market.

Rotterdam, currently showing at the Susan Caldwell Gallery on West Broadway, was sued by Newman in Small Claims Court for $1,000 in 1974. The suit involved the trade of an African sculpture for one of Rotterdam’s lithographs. The judge threw the case out.

Rotterdam remembers that Newman was the first person in New York to take an interest in his work, a fact he still appreciates: “The man is totally unpredictable. Without prior warning he does totally irrational things. He gets emotionally involved with the art. It seems like an obsession—one so strong that he would use any means to get the works—it’s a collector’s disease.” Rotterdam says that Newman has an impressive collection of relatively unknown works by young abstract expressionists, beautiful Japanese prints and German Expressionist drawings.

For those artists who remain enamoured with the notion of caviar trading, it would be best to follow Philipp Weichberger’s advice and not “fall for this man’s bait.” It would be safer, and in the long run, more economical, to buy the real game and deep-six “the fisherman.”