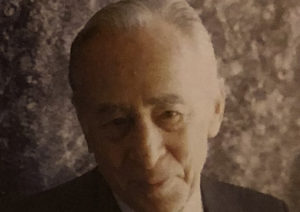

Leo Castelli, 1907-1999

In late July, Leo Castelli, right, collapsed during lunch with his wife, Barbara Bertozzi Castelli, at Sant Ambroeus, a favorite spot on Madison Avenue, and never recovered. He died on August 21 at his Manhattan home at the age of 91. As longtime Castelli artist James Rosenquist put it just a few days after his death, “This is the exclamation point for the end of an era.”

Upon his arrival in New York in 1941 from German-occupied Paris with his wife, Ileana Schapira Castelli, the Trieste-born lawyer and banker took a bead on the art world and never let go. His campaign began in 1951, when he organized the now famous “Ninth Street Show,” presenting 61 artists in the still nascent New York School in an abandoned downtown storefront. In February 1957, he opened the Leo Castelli Gallery at 4 East 77th Street and within a year introduced the electrifying work of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

He was representing Roy Lichtenstein, Rosenquist, Frank Stella, Cy Twombly and Andy Warhol by 1964, followed by Dan Flavin, Donald Judd and Robert Morris a year later and post-Minimalists Bruce Nauman, Richard Serra and Keith Sonnier not long after. Castelli opened a much larger venue in 1971 at 420 West Broadway in SoHo, and Conceptual artists such as Joseph Kosuth, Hanne Darboven and Lawrence Weiner became gallery artists, as did Ellsworth Kelly and Claes Oldenburg.

Castelli’s philosophy was perhaps best captured in a statement he made in 1990: “One has to accept what painters do. One does not have to like it, but one cannot disregard it. One can lament a certain fashion, but one can’t do anything about it. One cannot say: This is not art, it will go away. Who decides what is art? Who is responsible for the decision? Not I. Certainly not I!”

With his death, questions are being raised as to whether the Castelli gallery will continue, In the last year of his life, the dealer and his third wife, Bertozzi Castelli, a thirtysornething Italian art critic whom he married in September 1995. closed the 420 West Broadway space and reopened in a much smaller, though elegant, venue at 59 East 79th Street with a show of Jasper Johns monotypes. Plans for a fall show of sculptor Lee Bontecou, who showed with Castelli in the late 1950s, have been postponed as Bertozzi Castelli prepares for a memorial exhibition to her late husband, slated for later this month.

Charting a future for the gallery will not be easy. Just over two years ago, Bertozzi Castelli was blamed in some quarters for engineering a palace coup at 420 by dismissing Castelli’s longtime administrative team: gallery director Susan Brundage; her sister Patty, the associate director; and registrar Mary Jo Marks. In addition, at about the same time, according to several knowledgeable sources, the then recent provision in Castelli’s will to give the three loyalists a one-third interest in the gallery upon his death was removed, with that one-third interest apparently reallocated to Bertozzi Castelli. The other two-thirds are believed to be going to Castelli’s children—Nina Sundell, his daughter from his first marriage, to Ileana Schapira (who became Ileana Sonnabend); and Jean-Christophe Castelli, his son from his second marriage, to the late Antoinette (“Toiny”) Fraissex du Bost. Sundell declines to comment about the gallery’s future. Jean-Christophe Castelli was not available for comment.

The dismissals, according to several informed sources, outraged Nauman, who pulled all of his works from the Castelli gallery, moving them to Sperone Westwater in SoHo, where he had exhibited over the years. Nauman’s departure was just the tip of the talent iceberg of onetime Castelli artists who, in the last several years, have quietly found other representation. “Apart from Jasper Johns, I don’t know who else there is who hasn’t already found some other gallery connection,” says one Manhattan dealer. Rauschenberg, for example, has been showing new work at Pace Wildenstein since 1996; Stella has freelanced with shows at Knoedler & Co. and London’s Bernard Jacobson, and has a show at Sperone Westwater scheduled for November; while Rosenquist has been affiliated with

Richard Feigen in New York and the Baldwin Gallery in Aspen, Colorado. “Leo’s first and foremost interest was getting people to see the art of those he felt were important,” says Susan Brundage, who coincidentally, joined Sperone Westwater this summer. “The artists hung around because of Leo, and the staff did, too.”

Recalling the “Saturday Night Massacre” dismissals, Rosenquist says, “I sent Leo a fax and asked, ‘Who do I talk to about past, present and future business? I didn’t know what to do.” There’s still “nobody to talk to there,” Rosenquist continues. “I really don’t believe Barbara knows much about the art world or about the people in it.”

That viewpoint is vigorously contested by Morgan Spangle, cofounder of the ArtGroup.com, a Web site for fixed-price gallery sales slated to debut in October, and a Castelli alumnus who stepped in to run the SoHo gallery following the Brundage firing, leaving in June 1998. “Before Leo died he was really concerned that the gallery continue, so Barbara and lots of other people working with her have been thinking about this,” says Spangle, who had spoken with Bertozzi Castelli the day before his interview with Art & Auction. “I know there are plans in the works for the gallery to go on.”

Asked if Johns would continue to show at the gallery, Spangle says, “I see no reason for Jasper not to continue on. He’s got a long history there. But, of course, that kind of stuff is very hard to predict.” (Johns could not be reached for comment.) “The thing is,” says’one savvy Manhattan dealer, “there was only one artist [jasper Johns] left in that stable, and he doesn’t have to go anywhere. Anyone who thinks he’s looking for a gallery just doesn’t understand him.”

Whatever motivates the posthumous run of the Leo Castelli Gallery, the dealer’s place in the history of contemporary art is splendidly secure. “Leo could have rested on his laurels since 1968,” says Robert Storr, a senior curator in painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art. “Yet he kept at it. Nobody in the world of talent identifiers bats .500, but he came as close to doing that as anyone.”