Jesse Aaron, Bulldog, 1969

The self-taught and unself-conscious art of some genuinely primitive geniuses.

Voodoo has come to Los Angeles Under the guise of Sam Doyle, a seventy-six-year-old painter from St. Helena Island, South Carolina. Dr. Buz (enamel paint and tar on metal with conch shell), features the island’s best known voodoo doctor, listening to a conch shell. He might be diagnosing the sensation of lizards running wild in the bloodstream of a possessed patient. Dr. Buz is resplendent in blood-red pants, poised like an Olympic high-jumper, with one arm thrust before him. His name is emblazoned across the top of the painting that once might have been the door of a tin shed. An out-of-place-looking attaché case rests at the doctor’s feet, no doubt holding powerful potions.

Doyle the painter has never dialed a phone or driven a car. He did attend the opening of the Black Folk Art show at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in

Washington, D.C. As Corcoran curator, John Beardsley noted, Doyle wasn’t about to tempt fate by dialing hotel room service Dr. Buz might be listening.

With the current rash of neo-primitive street urchins running successfully amok in some major New York art galleries, it is with a welcoming whoop of victory that we greet some genuinely primitive geniuses who are called—for lack of a better label— Black Folk artists. Just as the French-man, Henri Rousseau, was “Le Douanier” in the 1880s because of his duties as a customs official, the fantastic line-up of artists unleashed by the Corcoran Gallery of Art must live with the unwieldy and one-dimensional classification, Black Folk artist, While it is helpful to separate these artists from the Life magazine, Grandma Moses-type of Sunday painter, it does not pack enough punch to turn heads. Critics, after all, were fond of labeling Rousseau’s art “le style concierge” before Apollinaire, Picasso and Vol- lard championed his work. Similar danger exists for the twenty artists showcased by the Corcoran, who come from primarily rural locales in the South, collectively unschooled and steeped in religious conviction. To borrow a phrase from one who somehow punched his way into American art his- tory (Horace Pippin, 1888-1946), “pictures just come to my mind and I tell my heart to go ahead.”

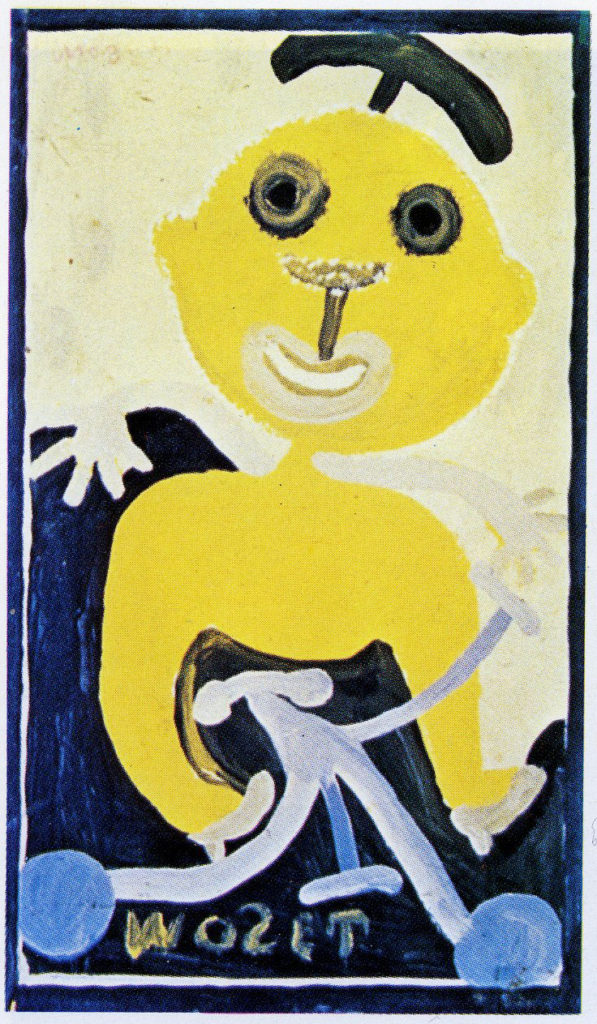

Mose Tolliver, Figure on bicycle, 1975, Enamel on wood, Courtesy The Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Of the twenty black artists contributing 400 objects to the traveling show (following the installation at the Craft and Folk Art Museum in Los Angeles, the itinerary jumps to the Institute For the Arts, Rice University, Houston Texas from March 4 to May 15, 1983), eleven are living, mostly in the rural South. The youngest, James ‘Son Ford’ Thomas is fifty-six. Elijah Pierce is ninety.

Ford, an acclaimed blues guitarist and composer, has performed in Northern Europe, and in general has made a living from his music, not his sculpture. To celebrate the Brooklyn museum opening last July, Ford performed his special brand of Mississippi Delta blues in the atrium of a midtown Manhattan skyscraper. Ford’s gris-gris heads of unfired clay and paint with corn kernels for teeth and clumps of cotton for hair, produce goosebumps on viewing. They fit in well with the contemporary cult of revering ugliness or badness. The calendar has to be pushed considerably back to get an accurate reading of the roots of “bad painting,” despite the convenient watershed of Marcia Tucker’s daring show at the New Museum in 1978.

Music is a trusty dip-stick for gaug- ing the phenomena of black folk art painting and sculpture, especially when comparing it to the more tame fare of white folk art, familiarly on hand in museums, galleries and auction houses (an exception would be the showing of the Reverend Howard Finster at the New Museum). The narrative style of country music clashes with the emotive medium of black-generated blues as heard in Clifton Chenier’s Black Snake Blues. Crudeness becomes a virtue and as the gospel singers belt it out, the apocalypse is salvation. The music analogy comes from John Beardsley who organized the exhibition with Corcoran associate director, Jane Livingston.

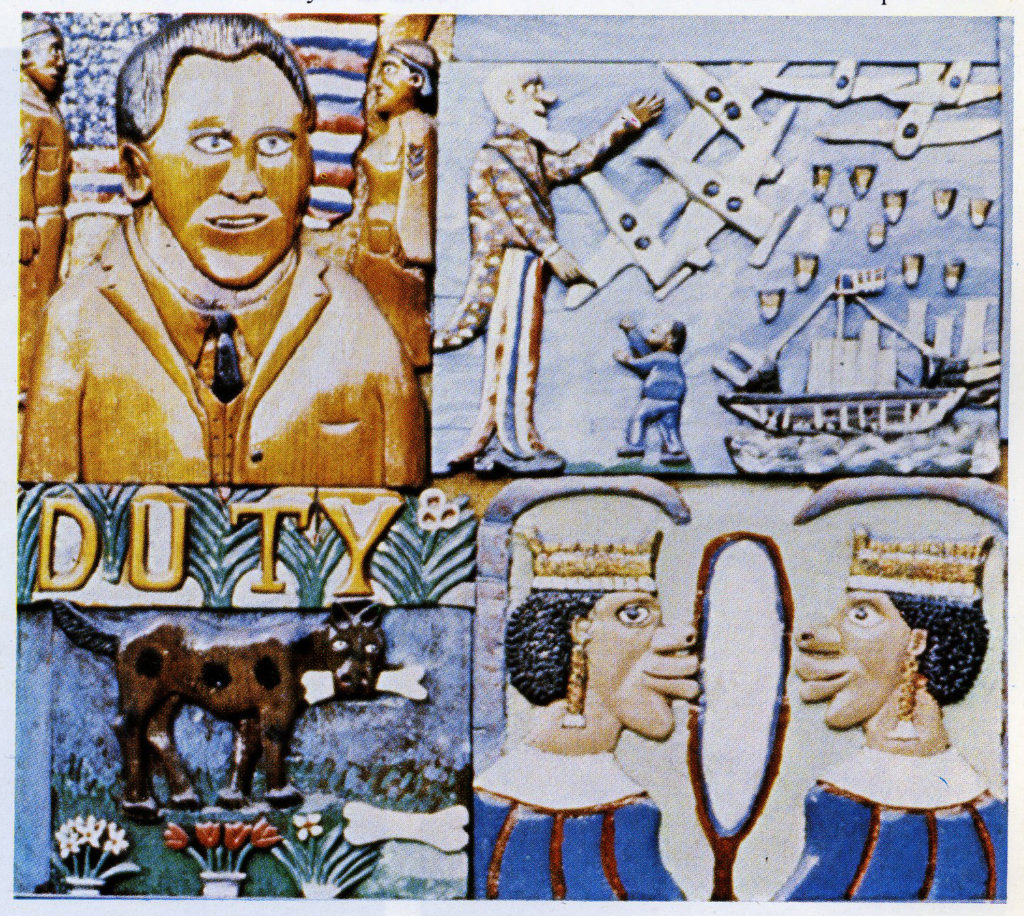

Elijah Pierce, Pearl Harbor and African Queen, 1941,

Carved and painted wood, 233 x 263 inches, Courtesy The Brooklyn Museum, New York.

This self-taught and unselfconscious art has been collected by southern folklorists, Afro-American art historians and a small number of “city slicker” artists (Roger Brown is a choice example), but the public has rarely seen the fantastical treasures created in weed-covered backyards and bay rum scented barbershops.

The tinderbox atmosphere of the show overwhelms previous notions of folk art as amusement. There are no quilts or weather-vanes in the exhibition. There are menacing totems of chain-sawed cedar (Jesse Aaron), tin- snipped whirly gigs (David Butler) and cut-out cardboard heads (Luster Willis) that rock the senses. It is infinitely more pleasurable to experience true-grit naifs than the momentarily popular fey-naifs that crowd some contemporary stables. Given the senior citizen status of the participating artists and the unheard-of creative juices that flow through their gnarled fingers, it is not unreasonable to accept the documentation of divine commandment that triggers their work.

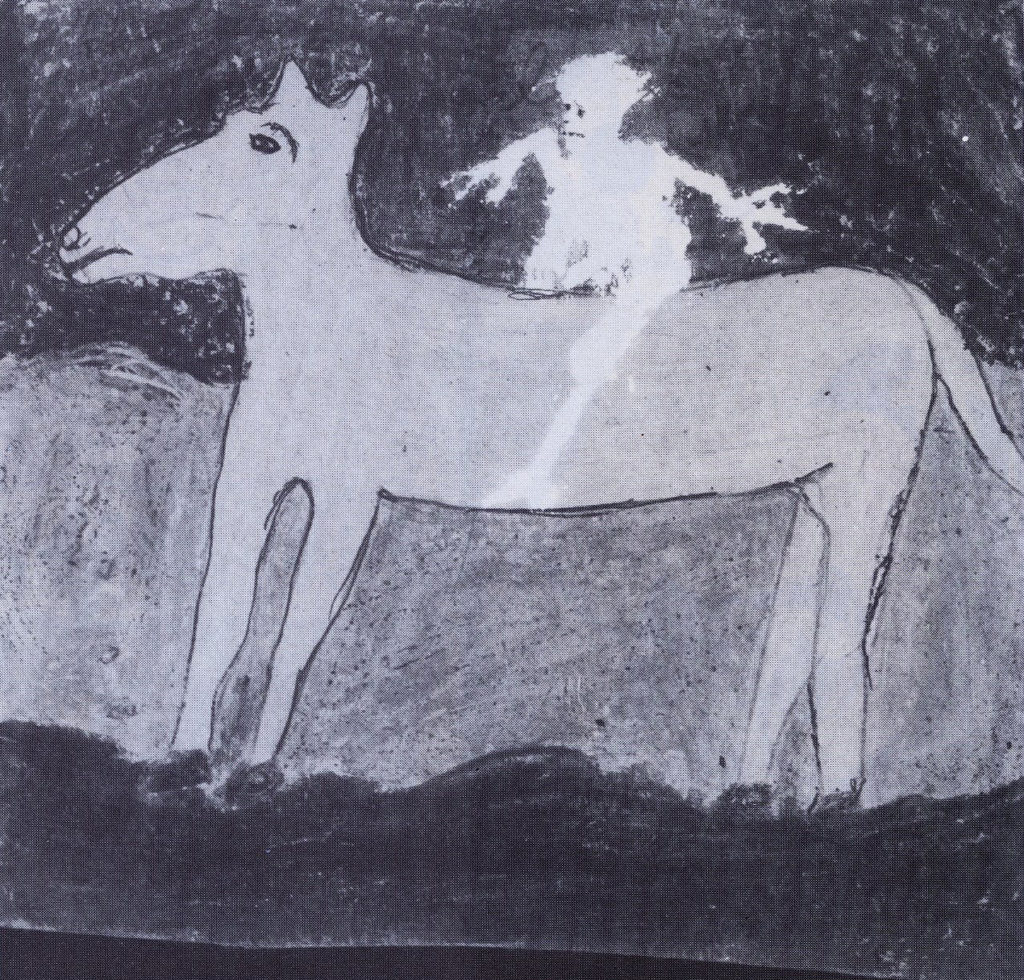

Bill Traylor, Self-portrait,

Courtesy The Brooklyn Museum, New York.

A slight shrug of the shoulders accompanies the statement that a Picasso or Van Gogh inspires an artist. Jesus is another story. If street preacher, Sister Gertrude M organ from New Orleans were here to tell it, “Jesus is my airplane.” Sister Morgan roamed her parish in a sparkling white uniform, befitting the bride of Christ. Her piano and house furniture were done up in white as well, with her pastel and watercolor paintings of revelatory biblical scenes consuming her home. Sister Gertrude’s guitar case, window shades and fireplace screens received similarly expressive treatment. Sister Gertrude had her own room in the show, painted white of course.

William Edmundson (1870-1951) carved limestone tombstones, “critters” and “garden ornaments” from the remains of demolished city buildings and curbs of Nashville, Tennessee. “This here stone and all those out there in the yard come from God. It’s the work in Jesus speaking his mind in my mind. I must be one of his disciples. These here is miracles I can do. Can’t nobody do these but me. Jesus has planted the seed of carving in me.” (see Edmund Fuller’s Visions in Stone, the Sculpture of William Edmundson, Pittsburgh Press, 1973). Edmundson called God, “heavenly daddy.” He would have remained obscure if it hadn’t been for a determined and well-

connected photographer, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, who worked for Harpers Bazaar in the 1930s. Her publisher, William Randolf Hearst, refused to run pictures of black men in his magazine. Wolfe turned around and planted the photos in the lap of Alfred Barr, of the Museum of Modern Art, who passed the material on to curator Dorothy Miller. So in October 1937, Edmund- son became the first black person to show at MOM A with a modest twelve sculptures. In 1938, one of his stubby limestone angels crossed the Atlantic for inclusion in the Miller-organized “Three Centuries of Art in the United States” at the Jeu de Paume in Paris.

Sister Gertrude Morgan, Vision of Death, 1965/75, Ink and acrylic on paper, 7 x 8 inches Photo Joel Breger

Edward Weston photographed a radiant Edmundson in carving goggles, rolled-up jeans, long apron and dusty workboots. Smitten by the work, Wes- ton stipulated that one of the sculptor’s angels should decorate his grave. Edmundson provides historic link- age to the mesmerizing patchwork of riveting images that stampede the exhibition. Although the Museum of Modern Art first showed folk painting in 1932 with the catchy title, “Modern Primitives,” Juliana Force, director of the Whitney Studio Club, exhibited American folk art as early as 1925. It was a time when Shaker furniture caught the fancy of Charles Sheeler and black jazz musicians from Harlem were hailed as folk artists.

The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis mounted an ambitious exhibition, “Naives and Visionaries” in 1974 that included the Gaudi-like spires of Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers and James Hampton’s The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations Millenium General Assembly. But the Brooklyn extravaganza was a curatorial coup, heralding black folk artists as a cohesive group.

Luster Willis, Man in white glasses, 1976. Tempera on paper, 10 x 12 inches, Photo Joel Breger

It is rare enough to have a practicing barber exhibit in a prestigious American art museum, but to have two, Elijah Pierce and Ulysses Davis, under the same roof, is dumbfounding. Pierce converted his Mississippi barbershop into the Elijah Pierce Art Gallery. His woodcarved tableau of prizefighters and aproned scullery maids are narrative masterworks. Ulysses Davis’s epic series on the thirty- nine United States presidents in eight-inch-high, carved mahogany busts are a tour de force of ambition and execution. Teddy Roosevelt’s pince-nez glare and walrus mustache vie for attention with Ronald Reagan’s lockjawed grin and brushed-back pompadour. All the hairstyles are exquisitely ingenuous.

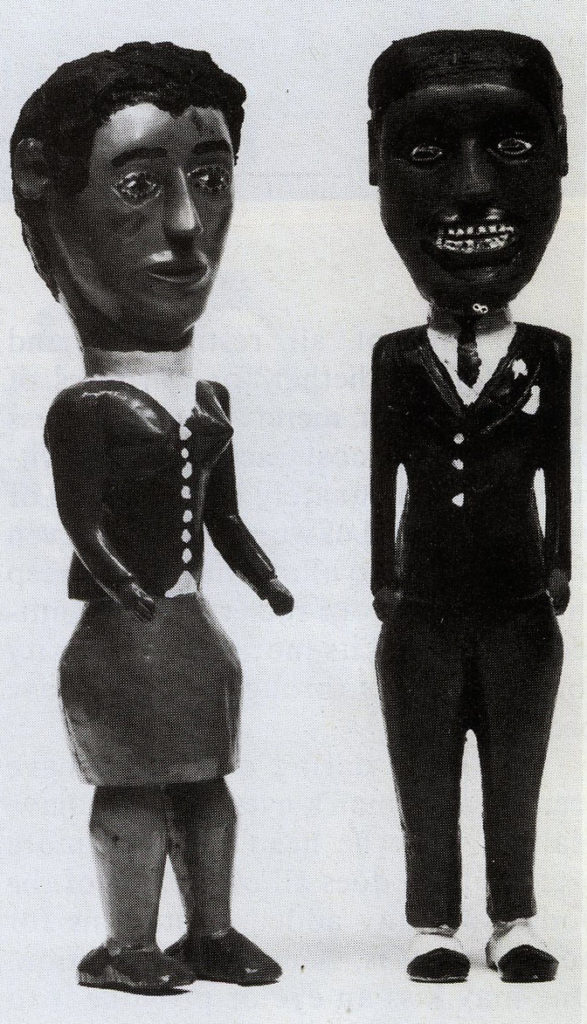

George Williams, Standing woman, clothed / Standing man, clothed, 1977,

16 x 3 inches, Photo Joel Breger

When Joseph Yoakum died in Chicago in 1972, he left behind a coterie of New Imagist artists like Christina Ramberg, Roger Brown and Jim Nutt, who revered his quirky pen strokes and magnetic application of taffy colors. The winding mountain roads of national park landscapes careened in abstract swirls, their exotic locations jotted down in a humble ballpoint scrawl. Fame followed Yoakum posthumously, with exhibitions at the Phyllis Kind Gallery and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. Even the staid Art Institute of Chicago was persuaded to accept a significant gift of Yoakum’s drawing, an unheard-of incursion. The Art Institute’s collection and the National Museum of American Art’s permanent installation of James Hampton’s gold and silver foil Throne Room are two rare examples of black folk artists piercing the snobbish armor of the fine art museum world. While Hampton’s cipher-coded „ assemblage of cloaked furniture and burned-out light bulbs graced the Corcoran installation, the work was deemed too fragile for travel.

How do urbane, and for the most part, non God-fearing subjects fathom the sources of these fantastic images? Dreams, revelations and absolutely fertile imaginations goaded “untrained” artists like Jesse Aaron to place a felt hat on the head of one of his terrifying totems with egg-yolk eyeballs. The immediate correlation to Joseph Beuys short-circuits as you consider Aaron’s splendid isolation in Gainesville, Florida. Although Aaron insisted that “God put the faces in the wood,” his Bulldog in cedar, fiberglass and bone, and Pig’s head in burnt wood, match the ferocity of Francis Bacon and Edvard Munch.

The question mark of roots trails the erotic oeuvre of Mose Tolliver’s paintings. They conjure up similarities with Odilon Redon for a romantic instant. The perspective fades and another image slaps you in the face. Moosehead with Antlers is just that. The wood panel jumps out at you and seems to veer into Schnabel country, terrifying the inhabitants along the way.

With its comprehensive catalogue (published by University Press of Mississippi) and far-reaching itinerary, “Black Folk Art in America, 1930-

1980,” should convert a substantial horde of skeptics to the cult of the naive. Just as Elvis Presley, the Beatles and The Rolling Stones mined the underground labyrinth of the blues for mass consumption and profit, black folk art can be digested by a new wave of artists intent on finding visual roots. Whether it be a Calvin Trillin from the New Yorker, reporting on the wizardry of Simon Rodia’s towers, or a lucky tourist stumbling on the roadside attractions of Steven Ashby, the innocent patina of folk art can be peeled away to reveal its brutal beauty. Con- sider the barb-tongued gospel lyric that Sister Gertrude strummed on her hand-painted guitar: “Satan in always just below your feet, looking for his chance, and you got to say, ‘Get back! You low-down crawling devil. Get back! You biting thing!'”

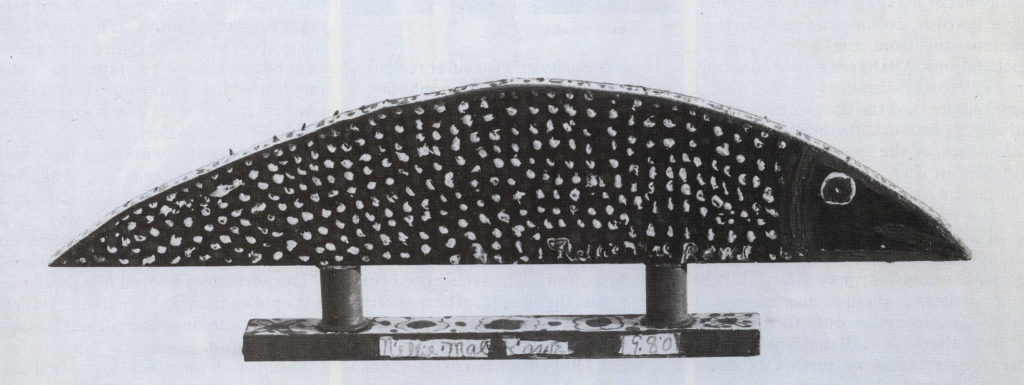

Nellie Mae Rowe, Fish on spools, 1980, Acrylic on wood, 7 x 25 x 1″, Photo Joel Breger