A watch fob congratulating the Boston Pilgrims (later the Red Sox) on their 1903 World Series victory.

When did the market for baseball memorabilia get so out of control?

A question of utmost importance to American men: Were you the sort who flipped baseball cards with your friends, and chewed the stiff pink rectangles of gum that came with the cards in that waxy wrapper? Are you by chance hoarding your collection of cards in some attic somewhere? If so, you may well be sitting on a small fortune. The baseball card as collectible is now so certifiably a phenomenon that at least one daily newspaper, the New York Post, has a regular columnist who deals in the ups and downs of the baseball card market.

But cards are just the beginning of the mushrooming collectibles phenomenon known as baseball memorabilia. Taking in everything from faded flannel uniforms to stadium souvenirs from yesteryear, thriving in venues that range from weekend baseball card trading shows to the Upper East Side showrooms of the Phillips and Christie’s East auction houses, the market packs as much of a wallop as Jose Canseco. The bubble gum that wrecked your teeth can now make you rich.

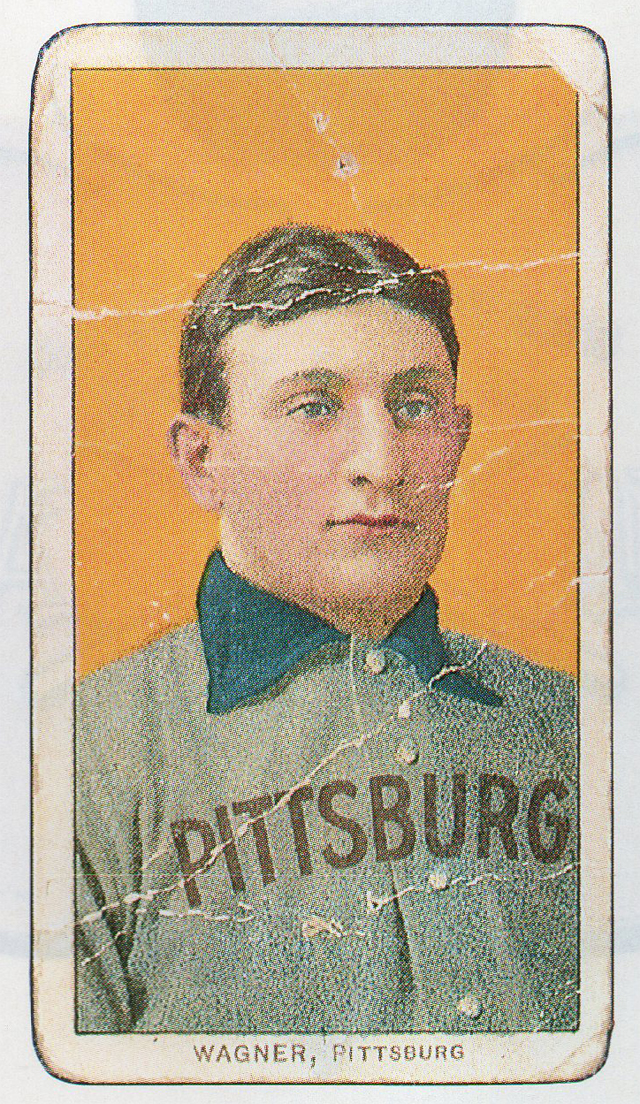

The T-206 Honus Wagner, the world’s most valuable baseball card.

“Batter hits a low-line hit to my right. I dove for the ball and caught it with my bare hand about three inches from the ground. My jump took me head first into the ground and I came up with the ball and made a double play “That breathless account, in wavy long-hand, by the Pittsburgh Pirates’ star shortstop of the early part of this century, John Peter (Honus) Wagner, was written to a pen-pal fan; it sold for $1,045 at Christie’s last September in an inaugural sports memorabilia auction. Perhaps an even more impressive sale at the same auction was of the 1903 World Series watch fob and pocket watch that once belonged to Fred Parent, the Boston Red Sox hero; it fetched $7,700—double its low-end estimate.

What is all the fuss about? Eric Alberta of Christie’s East, the man who introduced baseball collectibles to the august auction house, has his own theory “Baseball is our national sport, and as such, there are tons of memorabilia go-ing back nearly 150 years,” he says. “It has been saved because people love looking back. And it is starting to be recognized more as part of our social history”.

Baseball cards themselves are just a hair over a century old. Back in 1886, the New York firm of Goodwin & Co. introduced the cards as a premium in packs of Old Judge cigarettes. Borrowing from the British tradition of packaging colorful trading cards—usually either bathing beauties or military uniforms—with tobacco, the com-pany produced sepia-toned wood-cut portraits on thin cardboard stock; the subjects were players for the New York National League Club, as it was called before it be-came the Giants. The fact that more than half of that club eventually landed in the Baseball Hall of Fame has been as important in pushing the cards’ prices up (they’re now in the $300 range) as any consideration of the cards’ historical importance.

The ultimate card—as even some non-baseball fans know—is the phantom “T-206,” a product of the American Tobacco Company. You probably know T-206 better as the Honus Wagner (remember his letter?) card. Churning out cards that went into no less than 16 brands of cigarettes between 1909 and 1911, ATC blanketed the nation with sturdy color lithographs printed on white cardboard. The story goes that Wagner, a clean liver by all accounts, objected to being associated with the evil weed and intimidated the tobacco company into pulling the card out of distribution. The few extant cards, showing the barrel-chested short-stop plastered against a bright orange background, are worth anywhere from $30,000 to $45,000, depending upon condition and who’s doing the estimating.

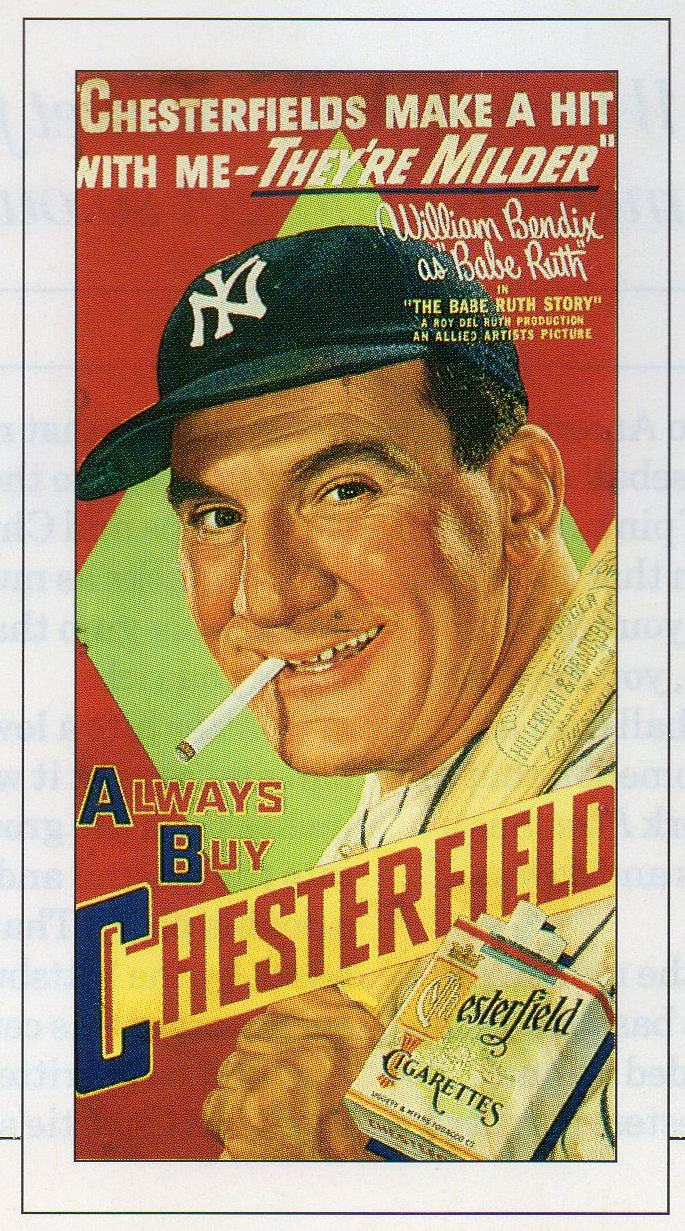

A poster on which William Bendix (star of the 1948 biopic The Babe Ruth Story) plugs his favorite cigarettes.

The collecting frenzy that started with cards has now spread out to encompass practically any-thing with even a tangential link to the game. What is a baseball collectible? “Almost anything connected to baseball,” muses Peter Clarke, registrar at the Louvre-like National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

“We even collect objects—parts of historic ballparks that have been razed. We have seats from Ebbets Field”—shrine of the old Brooklyn Dodgers—”and bricks and home plates from the Polo Grounds” hallowed turf of the Giants and, for their first, spectacularly inglorious season in 1962, the Mets.

Clarke keeps track of the roughly 25,000 objects in his Hall’s collection, of which between 40 and 50 percent are displayed at any one time in the facility’s 50,000 or so square feet of space. Items on dis-play range from Babe Ruth’s bowl-ing ball—he was a threat in a number of sports—to the first catcher’s mask, invented in 1876 by Frederick Thayer for his Har-vard teammate James Alexander Thing. The meat and potatoes of the collection, of course, are uni-forms and mitts belonging to great or otherwise notable players (“the older the better,” Clarke says), as well as baseballs that happened to be around when diamond history was made.

Clarke shies away from the commodity aspect of the national pastime—as the museum’s collection is paid for through donations, he can afford to—and he sees a growing danger in the demand for baseball collectibles. “All baseball memorabilia seems to be inflated these days,” he says. “I don’t know if the stock market crash of October, 1987, had anything to do with it, but now you’re getting the investor who has little interest in the game, plus the fan, and they’re both going crazy”.

It’s as if some people are trying to play catch-up with arguably the greatest collector of them all, Barry Halper, who in addition to being a part owner of the Yankees reigns over a museum-quality collection in the basement of his home in New Jersey Halper owns the batting helmet Hank Aaron wore when he clouted Number 715 as well as a life-size statue of Babe Ruth, in Yankee pinstripes, that once stood in Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum in London, and the autograph of every player—living or dead—ever inducted into the Hall of Fame.

With competitors such as Halper, how does a novice even begin to think of getting into this game? You might start with the gumshoe routine, following the trail of IRS agents scouting unre-corded cash transactions at week-end baseball shows in which famous players of the past and present scribble their John Hancocks on balls, bats, and biographies.

Or you might take the biblio-phile approach. Try a haunt along the lines of Manhattan’s wonderful Argosy Bookstore, where upstairs you’ll find old tearsheets from Harper’s Weekly, Journal of Civilization, circa 1865, that feature the somber team portrait of the Atlantic Base-ball Club of Brooklyn, Long Island. These guys, in their mutton-chop whiskers, look more like bankers than ballplayers, but the price of their picture is modest: $15.

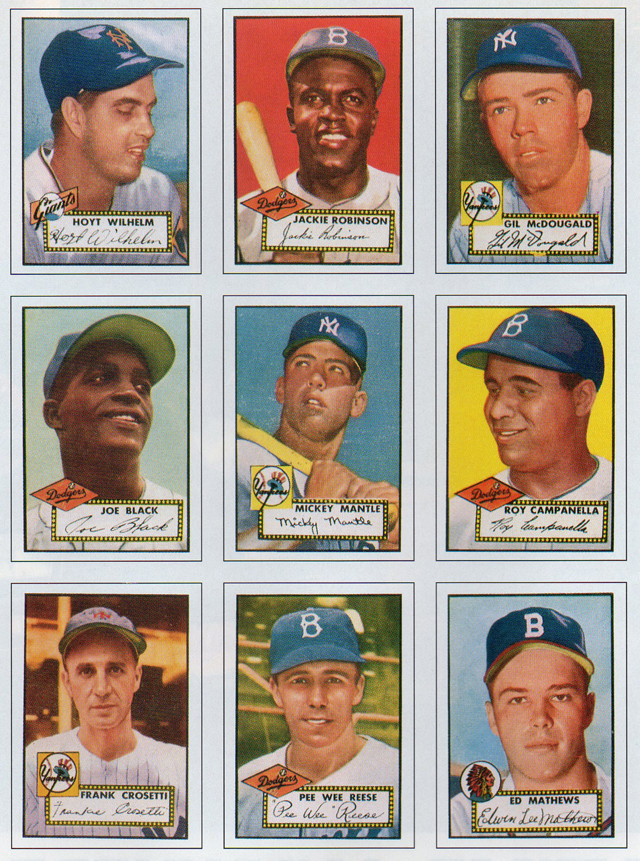

A brace of major-player baseball cards from 1952 season.

Ask Argosy’s Ruth Shevin if there is much interest in baseball-related prints, and she is likely to arch an incredulous eyebrow “The demand is there,” she says. “The material isn’t. You just can’t get it any more.”

Downstairs, similar distress signals went out in regard to an autograph of the immortal (but not very nice) Ty Cobb. High over Ar-gosy’s cash register was a huge matted frame containing a pale blue blank check bearing Cobb’s scratchy fountain-penned signa-ture; and above the check, a large black-and-white photo of our hero in action, stretching like a balle-rina in cleats to snare a line drive. The asking price was $325, and it went quickly Pestered for another, one Argosy clerk had a reply that should cause all prospective base-ball memorabilia collectors to wince: “It’s very hard to get base-ball stuff. If anybody has it, they don’t want to sell it.”

But not to despair All you need is patience and money That, and the faith that today’s baseball ephemera will be tomorrow’s hot tickets. Even ajar of Los Angeles Dodger manager Tommy Lasorda’s newly launched spaghetti sauce, now available on some supermar-ket shelves, might well strike the future collector’s fancy Of course, you’re always running the risk that Lasorda will get fired and the sauce will become a sort of epicu-rean Edsel. Still, with things going the way they are, it’s probably worth the trip down to the grocer’s.