As the market for departed artists heats up,

galleries get in line.

Parts Included – The studio of John Chamberlain, the last sculptor of discarded car parts and twisted metal, in Sarasota, Florida, in 1994

One of the most eye catching displays under the bespoke tent at last spring’s Frieze art fair in New York boasted a collection of large crushed-metal sculptures by the late John Chamberlain. But the Chamberlain-related chatter going around the fair was less about those artworks at the booth of Gagosian gallery—some of them taller than the viewers who stared them down—and more about speculation that the artist’s estate might leave Larry Gagosian for one of his archrivals among the world’s small coterie of mega-gallery dons. When Hauser & Wirth announced worldwide representation of Chamberlain less than three weeks later, the deal was done—and a new chapter began in the dynamic story of art world wheeling and dealing. Not long ago, rumors tended to swirl exclusively around which hot young talent one gallery might poach from another. These days, that kind of talk has come to encompass artists who are neither hot nor young—but dead. Major galleries have been battling intensively to add estates to their rosters in recent years, and not just for art that may have been left behind. They are driven by a number of factors, including the bursting of the 2013 market bubble around emerging artists, the desire to control an artist’s secondary market in the face of ever increasing competition from auction houses, and aspirations toward a kind of prestige that can help in attracting the best living talent. For those reasons and more, galleries of all kinds are getting into the game.

“There have been quite a number of estates that have been kind of sitting around, underevolved for years, if not decades,” Allan Schwartzman, a founder of Art Agency, Partners, a wholly owned subsidiary of Sotheby’s, said of what he called a current “arms race” for estates “looking to become reanimated from a new perspective.” And gambits among dealers competing for artists’ estates these days have become similar to the elaborate ways that auction houses jockey for prime holdings from collectors, including publishing plush mock-ups of auction catalogues and offering a wide array of financial options by way of cash guarantees, bridge loans, or buying works at beneficial prices to sweeten the pot.

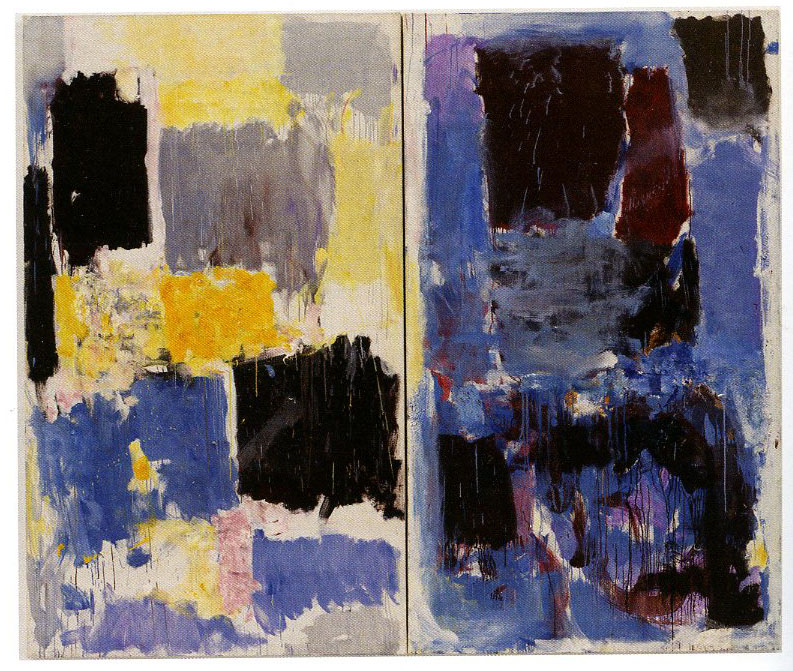

Going Home Again – The estate of Joan Mitchell— the painter of Untitled (1972)— went to David Zwirner gallery after years with Cheim & Read

It is not unusual for several galleries to make pitches before a sought-after estate makes its decision. “We received thoughtful and in-depth proposals from the world’s top galleries,” Chamberlain’s stepdaughter, Alexandra Fairweather, told ARTnews. “After careful reflection, we knew Hauser & Wirth was the right fit for us. As Chamberlain often said, ‘It’s all in the fit.'”

In 2018 the Joan Mitchell Foundation left Cheim & Read gallery after a market-boosting run of more than 20 years. After the sale of Mitchell’s painting Blueberry (1969) set a record for the artist at $16.6 million at Christie’s New York in May 2018, multiple galleries brought work by Mitchell to Art Basel, with speculation rife as to which dealer the estate might choose for future business. The answer proved to be another powerhouse: David Zwirner.

“Not long ago, rumors tended to swirl exclusively around which hot young talent one gallery might poach from another.”

“We did not solicit the foundation,” said David Leiber, a partner at the Zwirner enterprise with operations in New York, London, Paris, and Hong Kong. “We were approached by them after they gave notice to Cheim & Read that they were going to consider other options. They were looking for a different context for the work, a different space, and it seemed like a perfect moment. It was a rigorous process.”

One of the gallery’s selling points wasa promise to stage a high-profile Mitchell exhibition focused on multipanel works at Zwirner’s grand 20th Street showroom in New York. (That exhibition was on view this past summer; of the nine paintings shown, seven hailed from the Foundation, and sales of those ranged from $3.5 million to $10 million, according to Leiber.)

Leiber is no stranger to such maneuvers. In 2016 he played a role in securing the estate of Josef and Anni Albers—after the 2015 death of London dealer Leslie Waddington, its longtime representative—over competing proposals from Pace Gallery, Dominique Levy, and Hauser & Wirth, Zwirner’s most recent estate triumph, again with Leiber leading the charge, came this past April, when he brought on board the family of Paul Klee, which had been served for years by the private German dealer and author Wolfgang Wittrock. Plans are in place for a Klee exhibition at Zwirner in New York in September that catches tailwind from the centenary of the Bauhaus, where the artist taught.

Zwirner works with 22 estates, foundations, and families of departed artists. If that’s enough to make you think the strategy is to secure quantity for quantity’s sake, Leiber says it is definitively not. “The goal is not to add as many estates as possible and create this big, impressive playlist,” he said, “It’s really being selective—there has to be a very good reason. We also like to surprise our audience and ourselves with some of the choices we make. It’s not about market share or bragging rights. We think about what we could do for an estate—not just the occasional exhibition where the spotlight shines on an artist and then [dims] in the interim.”

The idea of maintaining energy around the work of departedartists is not exactly new. “Our mission after the artist was gone was keeping the representation of the art fresh and alive, and we worked very hard at that,” said Marc Glimcher, president and CEO of Pace Gallery, which was founded by his father, Arne, in 1960, “When we took over most of the Picasso estate and the Rothko estate back in the late ’70s, it started to become clear that this was not sleepy. This was something you had to put the same energy into as living artists—that was Arne’s hypothesis.”

But the amenities a gallery can offer an estate have multiplied since the mega-galleries started expanding, not just in terms of geographical scope, with outposts around the globe, but also specialized staff and new features in the art business. Five years ago, Zwirner, for

instance, launched David Zwirner Books, an ambitious publishing department that recently inked a deal with the powerhouse general-interest publisher Simon & Schuster. “We’re working all the time between shows,” said Leiber, “and there’s research to be done so we could add to the scholarship through the publications we do.”

Hauser & Wirth, which also maintains a robust publishing division, started signaling last fall that historical art and the secondary market would take on new, more formalized importance with the hire of two veterans from Christie’s: Liberte Nuti and Koji Inoue. Nuti will advise on the gallery’s work with estates and foundations as she researches and plans historical exhibitions to cultivate private secondary-market sales in the Impressionist and modern sectors; Inoue will do the same in postwar and contemporary. (The recent moves of multiple longtime auction house specialists to galleries—an aspect of contemporary galleries’ new focus on the secondary market—is related to the battle for estates. In 2017, Zwirner poached from Christie’s the estate of sculptor Ruth Asawa, along with Jonathan Laib, the Christie’s specialist who ran her estate.) Hauser & Wirth also demonstrated largesse and initiative in launching the Hauser & Wirth Institute, a New York-based nonprofit to oversee projects related to artists’ archives—and not just those in the Hauser & Wirth stable.

In the case of Chamberlain, Hauser & Wirth opens the September season in its uptown New York space with “John Chamberlain: Baby Tycoons,” an exhibition of a rarely seen series of works that the artist began in the late 1980s. And when the gallery debuts its new high-profile home base in the city’s Chelsea neighborhood next year, a major Chamberlain show will be one of the first exhibitions.

Among the Chamberlain estate’s chief goals for its new arrangement with the gallery are digitizing thousands of videos into a database for scholars, preserving Chamberlain’s live/work spaces on Shelter Island in New York, and laying the groundwork for a catalogue raisonne. “Gagosian did fantastic exhibitions and we enjoyed working with the gallery,” Fairweather said. “But now, as we look toward the future, we are excited

for the next chapter.”

Hauser & Wirth has perhaps gone the farthest of all the mega-galleries in the variety of amenities it offers its 31 estates and foundations. Fairweather pointed to the gallery’s “focus on scholarship, education, and community” and their “commitment to excellence across the board,” meaning not just exhibitions and publications but what she called “visionary initiatives” such as Hauser & Wirth Somerset, a hybrid gallery/hotel/ education center/residency program in a rustic setting in the town of Bruton, in Somerset, England.

And then there’s the power of marketing, for both the artists and the galleries themselves. John Good, head of estates at White Cube gallery, who works with the gallery on the estate of hardedge abstract painter Al Held (who died 2005), attributed part of the growing allure of artist estates to the way that mega-galleries like David Zwirner and Hauser & Wirth started snapping them up and putting them front and center in their exhibition programs. for the sake of both market potential and historical cachet. “Their marketing has changed the game,” Good said.

This past June, Hauser & Wirth published a hefty two-volume catalogue for Art Basel, complete with luxe photography and finely honed essays. One volume was devoted to the gallery’s living artists. The other, larger one focused on historical work and estates, including its newest addition, Chamberlain. In its Basel booth, Hauser & Wirth revealed three small Chamberlain sculptures that had never before been exhibited. Two of them sold, according to the gallery: PARISIA NESCAPADE (1999) for around $750,000 and COMEOVER (2007) for around $3 million.

More often than not, there is no vast collection of untapped work hidden away in an estate. But for galleries that is not necessarily a deterrent, as the benefit of representing artist estates is not limited to just working with holdings on hand. “In terms of participating in the secondary market of great masters, it’s a huge advantage if you are the gallery that represents the estate,” said Glimcher. “it’s much easier to go out and find the work that’s on the secondary market, even if there’s not that much work in the estate or the estate doesn’t feel like selling. That’s the business motivation behind all of this competition over estates.”

Good, who before joining White Cube had worked at Christie’s in private sales and before that handled the estates of David Smith and Alberto Giacometti for Gagosian, concurred. “When you’re working with an estate, you become the focal point of the resale market,” he said of the prospect of approaching owners of artworks they might be ready to sell, “If that’s valuable for you that’s a big piece of where the money is. You do a big show and people associate your name with the artist.” Then, when an owner of that artist’s work wants to sell and doesn’t go to auction, “the next logical place would be a gallery.”

One aspect of that is finding artists whose work appears to be undervalued on the market—so much so that the press tends to report estate additions to galleries in that manner. Upon breaking the news of the Klee family’s move to Zwirner, Melanie Gerlis observed in the Financial Times, “Klee’s auction record currently stands at £4.2m [$5.12 million! for his Divisionist work Tanzerin (Dancer), 1932, a much lower level than his contemporaries, including Pablo Picasso (auction record $179.4 million), Wassily Kandinsky (£33m, $39.8 million), and the lesser-known Alexej von Jawlensky £9.4m, $11.3 million).”

“We love to look at why something is undervalued and has potential to grow,” said Marc Payot, a partner at Hauser & Wirth. Noting previous auction highs for Chamberlain that have not surpassed $6 million, Payot imagines prospects for higher prices in the future. “We see this as a potential to focus and engage through content and research, and build the market off that.”

While Hauser & Wirth did not respond to a request for information on the value of the deal, sources with knowledge of it put it at more than $30 million. (Asked to quantify the deal, Fairweather commented, “I’m not able to disclose details, but the rumors are incorrect.”) Chamberlain’s auction record—$5.5 million for the 1958 sculpture Nutcracker at Sotheby’s last year—nudged up,just a bit from his previous high of $4.6 million for Big E (1962) at the same house in 2007. Such prices are low compared to other historically important artists of his generation such as Roy Lichtenstein, whose patinated bronze sculptures sell for as much as $10 million at auction.

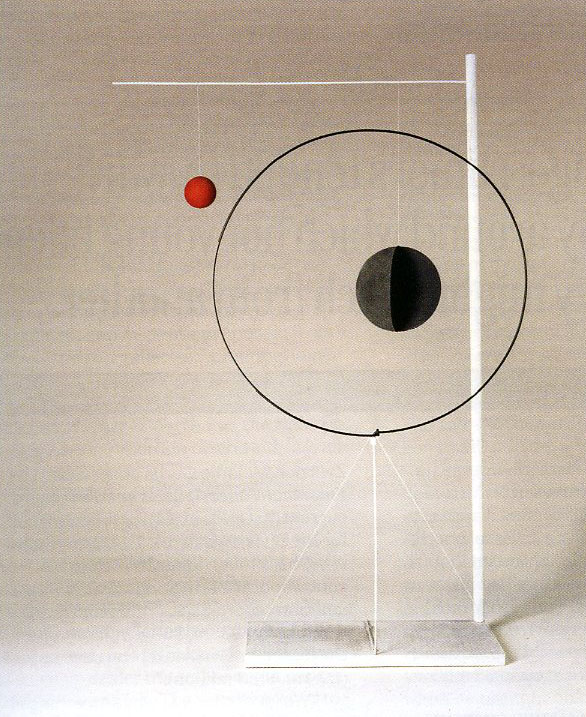

Mobile Service – Alexander Calder, Object with Red Ball, 1931

Alexander S. C. Rower, grandson of the late sculptor Alexander Calder and head of the Calder Foundation, is skeptical about promises to develop an artist’s market, “When a dealer pitches an estate,” said Rower, “they say, ‘Look, the market needs to be reset, and we are specialists in how to do it. We’re going to sacrifice three masterpieces that you still own and we’re going to reset the market’ This is the game.”

But when another gallery swoops in with a promise to do the same with other works that an estate might own, the cycle can turn into “an absurd comedy of errors that goes on,”Rower said. “Many estates have been fooled into doing this by established dealers.” Under Rower, the Calder Foundation has forgone working with any one dealer in favor of working on a project basis with many of them.

Raising prices can be a challenge if the market isn’t ready. As one market insider said, on the condition of anonymity, “The Chamberlain estate was difficult for Gagosian because the estate kept pushing the prices higher than what the market was—which is what an estate wants to do.” (Gagosian currently works with 16 estates and foundations.)

Of Hauser & Wirth’s investment in the Chamberlain market, Payot said he sees particular potential in the Far East, emphasizing that the gallery would work hard “until we get what we want in terms of the development of the market in Asia.” Hauser & Wirth is experienced with big bets in the region. Last year, when the gallery opened a space in Hong Kong, it put intensive effort into promoting a debut exhibition there for Mark Bradford, including mounting monumental video displays of the artist and his work on the exterior of a building for all the world to see. Payot also emphasized that Hauser & Wirth could become the “go-to place” for any activities involving Chamberlain and his decades-long career, and the gallery is “not only interested in the trophy piece that sells for whatever big amount,” but also in lower-priced works on paper and other materials that aid in understanding an artist’s overall significance in the world.

The addition of Chamberlain to the roster is valuable in other ways. For instance, it elevates Hauser & Wirth’s entire sculpture program. “Chamberlain is one of the father figures and Eva Hesse is one of the mother figures,” Payot pointed out. The gallery added the Hesse estate in 2000. It also works with the estate of another of those mother figures, Louise Bourgeois, and another father figure, David Smith (whose work also came over from Gagosian, in 2015). Works by Hesse have sold for as much as $4.5 million at auction, and in May of this year Bourgeois set a new record of $32 million for a spider sculpture (making her the highest-priced woman artist at auction). Works by Smith can go for more than $20 million at auction.

Showcasing the right estates can also enhance and strengthen relationships with living artists on a gallery’s roster and even help attract new talent. “Living artists really like and are interested in artist estates and the context they create for their own works,” said Lucy Mitchell Innes, co-founder of New York gallery Mitchell-Innes & Nash, which represents the estates of Nancy Graves, General Idea, and Sir Anthony Caro, alongside living artists like Pope.L, Justine Kurland, and Eddie Martinez. “You can easily see why an artist might want to be seen in the same gallery as de Kooning or Lichtenstein. It’s a prestige thing.”

Hauser & Wirth co-founder lwan Wirth has said his operation’s 20th-century program “contextualizes the art of the present and recontextualizes the art of the past. It works both ways.” And other galleries are also employing such a strategy, on a smaller scale. In 2017 the many-sited dealer Emmanuel Perrotin (Paris, Hong Kong, New York, Seoul, and Tokyo at that time) announced representation of French-German abstract painter Hans Hartung; last year, Perrotin teamed up with Simon Lee gallery and Nahmad Contemporary to stage major Hartung exhibitions sourced in large part from the decades-old Fondation Hartung-Bergman in Antibes. In early 2018, Perrotin’s show “Hans Hartung: A Constant Storm”—featuring nearly 70 paintings from 1922 to 1989 (the year of the artist’s death)—took over the gallery’s new building on New York’s Lower East Side, an area otherwise packed with outfits showing fresh-from-the-studio work by young and emerging artists.

Heir Patrol – Alexander S.C. Rower, grandson of Alexander Calder and head of the Calder Foundation.

Matthieu Poirier, the Paris-based curator who organized the show, said Perrotin gave him “carte blanche” to create a “museum-quality” exhibition accompanied by a hefty book. “It was the biggest exhibition of the artist’s work in the U.S. since the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s survey in 1975,” Poirier said, “and it created a great echo among professionals and clearly revived Hartung’s market.” Since Perrotin took on the estate,

Hartung’s record auction price shot From the $1.4 million set in 2015 to $3.2 million for a painting from the collection of Alain and Candice Fraiberger sold at Sotheby’s Paris in late 2017.

Galleries are introducing long-dead artists to younger clientele in new contexts. At the TEFAF fair in New York this past spring, David Zwirner gallery showed ten works on paper by Paul Klee, all from the 1930s; they sold nine of them at prices ranging from just under $100,000 to $300,000, according to Leiber. “They were mainly new buyers of Paul Klee,” he noted, “and, one could say, collectors who tend to focus more on the postwar period.”

The frenzy around estates has also spawned a mini-industry of advisory services for aging artists and their families as they plan for the inevitable. “There are very substantial estates and elderly artists who have art worth hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars, if not more,” said Schwartzman, the AAP co-founder. “There’s avast number beyond the obvious names, and there’s a lot of very meaningful work by artists who have been successful in their lifetime. They have a lot of art in storage, and there isn’t a well-enough-conceived legacy plan, so our focus has been both with living artists’ and estates’ legacy planning.”

When AAP announced efforts to expand its artist advisory service in 2016, the development met with skepticism from Marc Glimcher, of Pace, who told the Wall Street Journal, “for an auction house to represent a living artist is like MGM representing Fred Astaire—you can’t tie up all the sides of a transaction.”

“Galleries are introducing long dead artists to younger clientele in new contexts.”

But Schwartzman challenged that interpretation. “In all of our advisory work,” he told Artnews,”we try to be in the background. We do not want to get in the way of the gallery, and we especially want to respect the frontline role of the gallery.”

Similar in ways to the estate and foundation work at Art Agency, Partners, the newly formed Gagosian Art Advisory LLC under the leadership of former Christie’s rainmaker Laura Paulson is also gearing up to be a full-service component separate from Gagosian gallery, but headquartered in the firm’s Madison Avenue location.

“We’re not really dealing with artist estates,” said Paulson, “but certainly if an artist estate approached us, we could help with appraisals, management, and selling works of art from the collection of the deceased artist, similar to what I did [at Christie’s] with the estate of Merce Cunningham and the Cy Twombly Foundation. That’s more in line with what our role could be. I can also see where we could be helpful if [Gagosian gallery] takes on an estate and we could be a part of that full-service aspect.”

Paulson sees a striking parallel between the increasing number of artist estates that gain new gallery representation and the aging-out of gallerists who often forged those artists’ primarymarket careers. “it’s becoming a generational shift,” she said, “and the business has shifted to new hands to manage many of these estates.”

“The gallery relationship is really an important one for the artist estate,” said Loretta Wurtenberger, who in 2016 co-founded the Berlin-based Institute for Artists’ Estates. Wtiirtenberger advises and manages the estates of Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp (which are represented by Hauser & Wirth and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, respectively). “Most estates are financially dependent on sales,” she added. “So if that relationship doesn’t work, the estate is in trouble.”

| Gagosian | Hauser & Wirth | David Zwirner | Pace | |

| Gallery Spaces | 17 | 10 | 6 | 7 |

| Living Artists | 67 | 57 | 43 | 64 |

| Artists’ Estates/ Foundation |

16 | 31 | 22 | 25 |

| Residencies | no | Los Angeles, Somerset, Monorca | no | no |

| Online Viewing Room | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Independent Advisory Service | Gagosian Art Advisory, LLC | no | no | no |

| Independent Nonprofit | no | Hauser & Wirth Institute | no | no |

| Art/Tech Offshoot | no | no | no | PaceX |

| Publishing Arm | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Media Offerings | Gagosian Quarterly | Ursula Magazine | Dialogues podcast | no |

| Bookstore | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Restaurant Affiliations | Larry Gagosian with Kappo Masa (NY); Beverly Hills restaurant planned | Roth Bars (NY and Somerset); Manuela (LA); “a cantina” (Menorca) | David Zwirner with il Buco (NY) | no |

| Lodging Options | no | Durslade, converted farmhouse for rent (Somerset) | no | no |

| Livestock | no | Farm animals on site in Somerset; chickens at Manuela (LA) | no | no |

| Expanding | Basel, Switzerland, opened 2019, new Chelsea property aquired | 32,000 sq ft home opening in NY in spring 2020 | 50,000 sq ft building opening in NY in Fall 2021 | 75,000 sq ft building opened in Septemeber |

In the experience of Wurtenberger, also the author of The Artist’s Estate: A Handbook for Artists, Executors, and Heirs (Hatje Cantz, 2016), arrangements of the kind work best for all involved when galleries “show a deep understanding and enthusiasm for the work, to get the feeling that the gallery’s owner or the principals are really on fire for this work.”

Such arrangements aren’t always easy to find in mega-galleries that can have 50 to 70 artists and estates on their rosters, all vying for attention and with limited space at art fairs to promote it. And it’s by no means a given that any and all estates come armed with convincing visions for the future.

“The gallery,” Wurtenberger said, “is more motivated to work actively with the estate if there’s a lively body behind it.” Then again, there is arguably no livelier body behind a foundation than Rower, Calder’s grandson, and he cautions against putting too much stock in one-gallery relationships for artists of a certain stature. “I’m not looking for a guarantee of anything from anybody,” he said of how he runs the Calder Founda- tion. “Many estates I know approach me for advice, and I keep saying, ‘Just follow what we do’: be project-based. That’s the best thing you can do for an artist. If you need representation, you should examine why. What does that bring you?”

This fall, two rare and revolutionary ’30s-era Calder motorized mobiles recently restored to running order by the Foundation will be on display with other Calder works at Pace Gallery’s new eight-story flagship in New York. Both were acquired by the Foundation last year during the controversial deaccession of works from the Berkshire Museum in western Massachusetts. “We’re the biggest collector of Calder, not the biggest wholesaler,” Rower said. “Our collection has grown exponentially because we’re trying to have an even bigger collection of masterpieces to tell stories.”