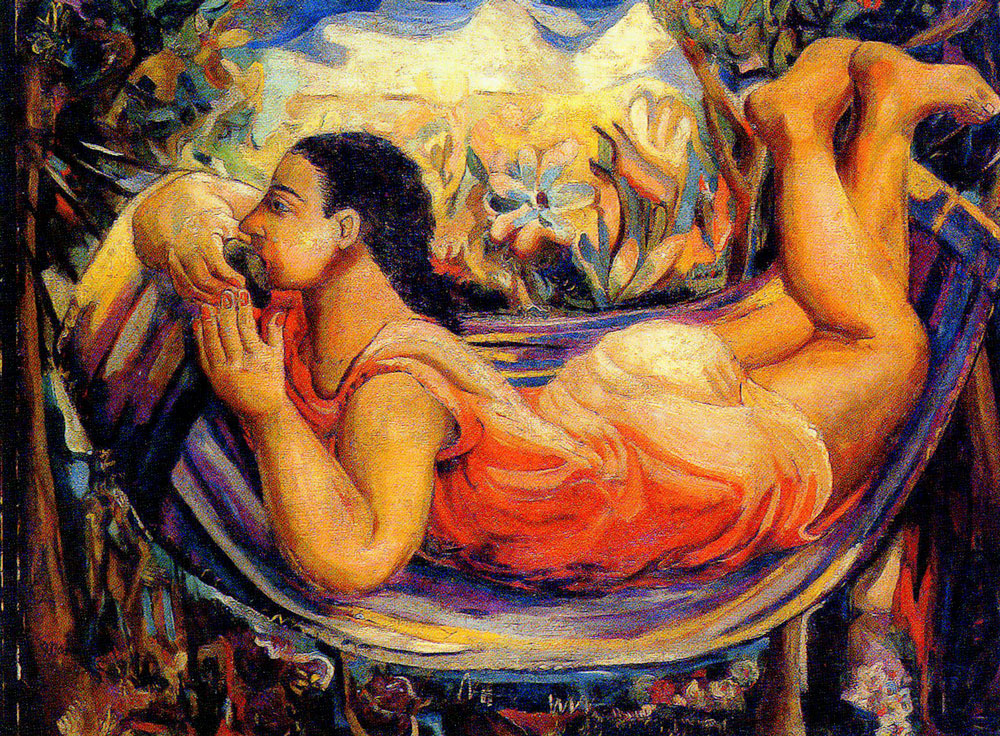

The oil on canvas La Hamaca, ca. 1941, by Mariano Rodriguez, was offered and then withdrawn from sale at Sotheby’s New York in May 2001, when the house learned it had been stolen from the family of Manuel de la Torre, a Cuban-American architect.

As relations normalize between the United States and Cuba, restitution cases involving misappropriated art are likely to proliferate.

With President Barack Obama’s announcement in December that relations between the United States and Cuba would begin to thaw after a 54-year-old diplomatic freeze came the prospect of a new era of restitution cases concerning artworks abandoned, confiscated, or otherwise lost to their owners during the Castro regime.

According to experts in the realm of cultural property, the potential number of claims is a fraction of those involving artworks seized by the Nazis yet it represents tens of millions of dollars. The restitution of, and compensation for, those works began in earnest only in the late 1990s, thanks in large part to efforts such as the Washington Conference on Holocaust-Era Assets and the availability of more sophisticated tools in provenance research.

“The art market has always focused on prove- nance when a work comes from a famous collection that adds value to it,” says Monica Dugot, international director of restitution at Christie’s. But a lack of provenance has not always hindered a sale. At the November 1989 auction of Important 19th-Century Pictures and Continental Watercolors at Christie’s London—in a time before such vigilant provenance research was in play—the 18-by-30-inch Jean-Leon Gerome cover lot, L’Entree du taureau, 1886, was sold to a European agent for £330,000 ($504,000).

The two-page catalogue entry for the lot did not include recent provenance; the last dated ownership was in 1943. The only indication of suspicious provenance was an italicized note at the end of the entry, which read, “United States citizens are advised that the sale and purchase of this lot may contravene U.S. regulations in regard to property emerging from Cuba and that such property is not available for import into the U.S.A.”

A strict U.S. trade embargo on Cuba has been in effect since February 1962, declared under the aegis of President John F Kennedy. (A storied cigar aficionado, Kennedy reportedly had an aide acquire 1,200 Cuban cigars before he signed the executive order.) While Obama called for ending the embargo during his January State of the Union speech, execution of such an order lies in the hands of Congress.

“I remember the Gerome had a massive health warning on it,” says Mark Poltimore, who at the time was the head of 19th-century pictures at Christie’s, “and our lawyers were very anxious that we not contravene any laws.”

Now deputy chairman of Sotheby’s Europe, Poltimore says the painting had come from the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Cuba. Beyond that, nothing is known publicly about how it entered the renowned Havana institution, much less how it wound up on the block at Christie’s.

How much art is potentially in question? Art restitution specialist Mari-Claudia Jimenez, a partner in the New York law firm Herrick, Feinstein ALP, cites a former registrar at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes who estimated that of the 50,000 to 55,000 works in the museum, perhaps 60 percent to 70 percent of them had been confiscated from their owners following the 1959 revolution. This eyebrow-raising statistic was first reported in a 2007 Art+Auction article by David D’Arcy, published when prospects for a détente between the United States and Cuba seemed dim.

The Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana, counts among its holdings Francesco Guardi’s Laguna con le Fondamenta Nuove, 1750-55, allegedly, appropriated from the family of Javier Garcia-Bengochea, a Cuban-American doctor.

Jimenez had previously worked with her Herrick colleague Lawrence Kaye to resolve Nazi-era art theft cases for the prestigious Jacques Goudstikker collection in the Netherlands, as well as the restitution of paintings by avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich to his heirs. She says of Cuba that “a regime change could lead to a situation where one could bring a claim in the United States, and that would certainly open the landscape in terms of court cases based on such claims.” Such a change, adds the Cuban-American Jimenez, whose own family suffered losses after they fled the revolution, “would ostensibly lead to some mechanism whereby claims could be brought by Cuban-Americans in Cuba, both for works that were taken from them and which are still in Cuba, and for works that are no longer in Cuba or cannot be found.”

Much has been written about once fabulously wealthy Cubans-like “Sugar King” Julio Lobo-who lost their fortunes and Old Master art collections after the revolution, or those who rebuilt their riches in the United States, such as the Fanjul family, which also had art confiscated by the Castro regime. One of the lesser-known candidates for restitution is Javier Garcia-Bengochea, a Cuban-American neurosurgeon in Jacksonville, Florida. According to the doctor, his family acquired Francesco Guardi’s Venetian scene Laguna con le Fondamenta Nuove, 1750-55, at Parke-Bernet in New York in 1957 for S1,000. The work had come from the estate of Marjorie Nott Morawetz, the widow of a wealthy lawyer, Victor Morawetz. The picture was taken to Cuba where family members shared possession of it.

“It was in our living room periodically in Santiago de Cuba,” recalls Garcia-Bengochea,”and it would go back and forth between one house and another. But

the painting ended up being left in Cuba with an old cousin and eventually wound up in the national museum there:’ The Guardi is widely mentioned in travel guides as a highlight of the Bellas Artes collection.

As the doctor recounts his many attempts to see the painting, to pursue a dialogue with relevant Cuban authorities about his claim, and to answer the question of how the Guardi got there in the first place, the multilayered complexity of restitution becomes apparent. “When I went back to Cuba in 2004,” he says, “I saw it in the museum and was happy it had resurfaced. We thought some member of the Communist Party had sold it on the black market, which is quite common there. When I went back

in 2010, the museum was closed for renovation. I went again in April 2013 and tried to make an appointment with the people in the museum, but no one would meet with me. They blew me off and don’t want to have anything to do with me.”

Asked what he thought the Guardi was worth in today’s masterpiece-hungry market, Garcia-Bengochea demurs, but he cites a similar Guardi, Venice, the Bacino di San Marco, with the Piazzetta and the Doge’s Palace, which sold at Christie’s London last July for £9.9 million ($16.9 million). “I’m frustrated,” says the doctor.”‘ know exactly where it is, but I can’t get to it.”

Ironically, Garcia-Bengochea says he noticed that the museum wall label for the painting cites Morawetz as a former owner but omits his family’s name: “The Cubans know enough about this painting to know that it was once hers, which means they know that it’s mine.”

The routes by which artworks confiscated by Castro’s regime may slip into the international art stream are narrower today than they were a decade ago, thanks in part to an agreement reached between Sotheby’s and the Fanjul family in 2005. Sotheby’s agreed that it would not handle any former Fanjul property and that, “should it unwittingly come into possession of any suspect works, the house will notify the family and maintain possession of such property until any title issues have been resolved.”

Spurred by the Fanjul case, Lucian Simmons, senior vice president of provenance research and restitution at Sotheby’s, says, “we adopted guidelines, which we distributed to all of our employees, alerting our experts in every department to be aware of art that was dislocated or looted-or whatever word you want to apply

to it-during that period. The guidelines are basically the same ones we issued for works of art dislocated during World War Il.”The goal, says Simmons, “is to filter out works of art which could be the subject of claims. We don’t want to expose our consignors or our buyers to any kind of claim.”

That predicament came up in May 2001 when Sotheby’s offered-and then withdrew from its Latin American art auction-a Mariano Rodriguez figurative painting, La Hamaca, circa 1941, estimated at $150,000 to $200,000. At that time, Manuel de la Torre, a Long Is- land-based Cuban-American architect, saw the work in a Sotheby’s advertisement in the New York Times and made the house aware of his family’s claim on the painting. Though there is a confidentiality agreement in place that bars both parties from speaking about the settlement, Sotheby’s did return the painting to de la Torre’s family shortly after his death in 2005, according to Ramon Cernuda, a prominent Miami-based Cuban art dealer and close family friend; it ended a four-year legal battle.

As Jimenez says, “There’s certainly not a forum in place to bring a case in the U.S. for something that’s currently in Cuba, but for artworks that are found on American soil there is definitely more hope and more room for possibilities.”