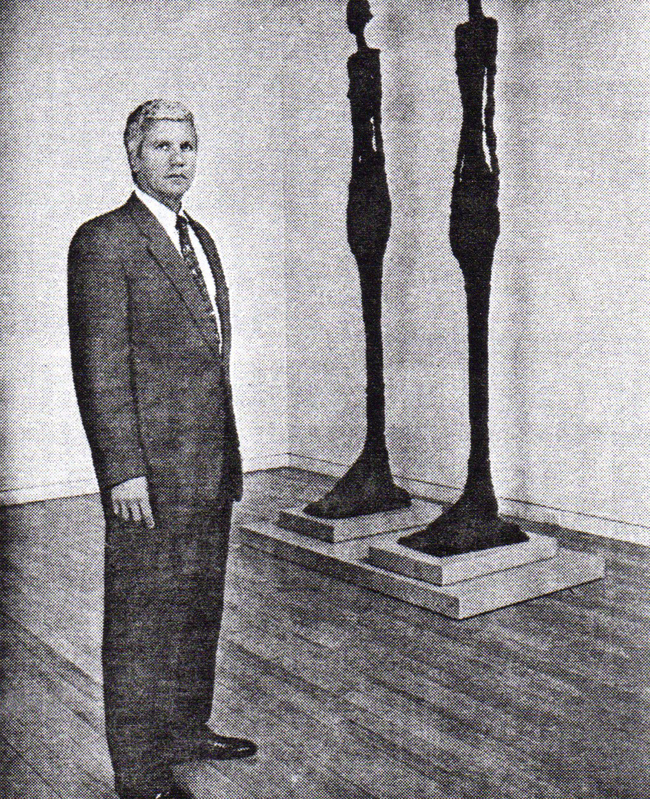

Art dealer, Larry Gagosian next to a pair of Giacometti sculptures at his Madison avenue gallery. Photo by Cori Wells Braun for the Washington Post

The moment is frozen in art market history. It is Nov. 10, 1988 and 43-year-old New York art dealer Larry Gagosian nods his head a final time in Sotheby’s packed salesroom to capture Jasper Johns’s 1959 painting, “False Start” for a staggering $17 million.

Dealer Larry Gagosian Has Survived the Collapse of Gallery Prices of the ’80s and Is Reaching Higher

A standing ovation greeted the record price. It was the highest ever paid for a work by a living artist, more than doubling the record that had been set only 24 hours before at Christie’s for another Johns painting. And it symbolized the arrival of the brash, well-financed Gagosian as a figure in the art world.

Sitting next to Gagosian that evening was the man for whom he bid the stupendous $17 million: S.I. Newhouse Jr., the billionaire publishing magnate (Random House, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker) and collector. It was an alliance of Big Money and Big Art – the sort of combination that Gagosian has come to epitomize.

Newhouse is just one of Gagosian’s super-rich clients who made their fortunes in media, entertainment and advertising. Gagosian, a graduate of Hollywood’s mogul-breeding mail room at the William Morris Agency Inc. in Beverly Hills, also hasbrokered multimillion- dollar art deals for Charles Saatchi, the British advertising giant, Keith Barish, the movie producer (“Sophie’s Choice”) and David Geffen, who is probably Hollywood’s richest show business figure.

Now that the runaway art boom of the 1980s has given way to the rude bust of the ’90s, Gagosian is operating in a different kind of market. But he remains a defining figure in the business of selling art.

Feared and envied by competitors, he embodies the dealmaking of a little-regulated industry, dominated by secrecy and brush-fire rumors. In the new, leaner and meaner market, Gagosian – much to the surprise of naysayers – has found new, deep-pocketed clients from the heap of 1980s collectors who tapped out financially or, in the dealer’s words, “got jerked around a little and lost interest.”

Even when Newhouse, his star client, stopped buying and took a chunk of hismuseum-quality wares away from Gagosian to Sotheby’s for private resale late last year, Gagosian shared part of the sales commission by bringing in David Geffen (another graduate of the William Morris mail room). While none of the principals would comment on the transaction, which is par for the course in this tight circle, one informed source close to a high Sotheby’s official pegged the Newhouse-Geffen deal at $40 million. Art market sources estimate that Gagosian’s commission was in the range of 3 percent, or about $1.2 million.

How is it Gagosian always lands on his feet?

With his Manhattan carriage house with indoor lap pool, a post- modern beach house in the Hamptons and a high-speed speaking style, Gagosian would seem an ideal candidate for an art-world remake of Budd Schulberg’s 1940s novel, “What Makes Sammy Run,” the breathless story of the meteoric rise of a young Hollywood studio executive. How did he do it?

“Larry’s very smart,” said David Geffen. “He’s extraordinarily adept at finding pictures and he’s very aggressive. He’s done an enormous amount of business with many of the top collectors in the world. Larry knows how to close a deal.”

Others would characterize Gagosian’s hardball style of wooing buyers and sellers in a different way. “It’s what people in the real estate business do,” said one prominent collector and museum trustee who insisted on anonymity. “He’ll find somebody who he thinks will buy something and then he’ll get the painting from a collector even though they don’t have it up for sale. It’s four, five, six times before you finally get him to go away.”

The Early Years

The Early Years Of Armenian background, the dealer grew up in Southern California, the only son of Ara and Ann Louise Gagosian. His father was a stockbroker who learned his craft at night school. The young Gagosian worked his way through UCLA. After his brief stint at William Morris – shuttling contracts and scripts to studio heads, actors and directors – Gagosian began his art career in the early ’70s with a tiny poster shop in Westwood Village, close to UCLA.

Gradually expanding, by 1978 Gagosian had his own Los Angeles gallery – the first using his name – exhibiting paintings by young and hot New York artists who craved a West Coast showcase.

Still in California, Gagosian was obliged to share sales commissions with New York dealers such as Mary Boone and Metro Pictures, who represented such emerging art stars as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Eric Fischl and Cindy Sherman. His unbounded pursuit of collectors and first-rate art works earned him his nickname, “Go- Go.”

As the contemporary art scene surged forward, Gagosian set his sights on New York, and in 1979 bought a loft on West Broadway. In his typical horse-trading style, the dealer paid $10,000 plus a Brice Marden abstract painting for the loft. Valued at no more than $30,000 at the time, Marden’s paintings now sell for more than $500,000, about the same value as Gagosian’s SoHo loft.

But the loft’s biggest value was the location, across the street from the venerable Leo Castelli, the dealer who discovered and launched the careers of Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol. Gagosian pursued Castelli’s friendship and influence with the same charm and energy he used to win over new clients and artists. Gagosian used the loft as a private gallery and social salon.

In many ways, Gagosian’s ascent to super-dealerdom can be divided into two acts: Before Leo and After Leo.

“No one took him seriously back then,” said Laura de Coppet, the coauthor with Alan Jones of “The Art Dealers,” a collection of mid- ’80s interviews with the art world’s best and brightest. Gagosian was not included, an omission that would be inconceivable today.

According to de Coppet, who is close to both dealers, Castelli’s initial impression of Gagosian as an arriviste dramatically changed when Gagosian offered to sell some of Castelli’s paintings on the secondary market (the resale of art works after the original transaction) following the death of Castelli’s second wife, Antoinette, in 1987. Substantial estate taxes had to be paid. In 24 hours, Gagosian turned around $1.5 million in art and delivered the check.

“That sealed the pact,” said de Coppet. “Leo was so terribly impressed by his business acumen. He embraced Larry. Since then, they’ve become very close friends.”

It was Castelli who introduced Gagosian to Si Newhouse, his longtime client and a major buyer of Pop Art works. The younger dealer became Newhouse’s exclusive agent in the secondary market. “It’s not true that we’re partners,” Newhouse told Vogue (a Newhouse publication) in a rare interview in 1989, “but I’ve bought so much from him that I’ve probably had a major role in his success.”

Even before his fruitful alliance with Castelli, Gagosian’s outsider status had begun to change when he opened a vast, street- level space on the dingy west end of 23rd Street in October 1985, far from the trendy precinct of SoHo. The art world had to take notice.

Putting on retrospective shows of contemporary and modern art became a Gagosian trademark and magnet for drawing in a larger public as well as serious reviews.

He scored a major coup by showing part of the legendary Pop Art collection assembled by Burton and Emily Tremaine in his inaugural exhibit. Everybody that counted in the gallery-auction arena wanted a piece of the Tremaine collection. Gagosian got there first.

Though it wasn’t part of the show, Gagosian also sold the Tremaines’ prized diamond-shaped abstraction from 1944, “Victory Boogie-Woogie” by Piet Mondrian, to S.I. Newhouse for a reported $12 million, in 1985 an unheard-of price for a modern work of art.

How did Gagosian, a dark-horse contender without much of a track record, win over the Tremaines by cold-calling them on the telephone?

“I was very persistent and luckily, we hit it off,” said the dealer during an afternoon interview in his art-lined inner sanctum, a discreet part of the huge duplex/penthouse gallery (complete with a landscaped sculpture terrace) he now maintains on Madison Avenue.

“They were intrigued by the idea and the timing was right for them. They were in a mood to sell.”

Oddly enough, Gagosian characterizes most of his business relationships this way – the less detail, the better. When asked for examples of specific deals, clients, commission charges and gallery turnover, the dealer smiled tightly and said, “I’m not statistically oriented. I don’t want to talk about specific people. I’m not going to lay out a road map about how I run my business.”

Candid, to a Point

Candid, to a Point The interview continues at a friendly clip and the dealer delivers a few intelligent sound bites on the state of the market or the quality of a particular painting. But that’s as far as it goes. Gagosian, who bears more than a faint resemblance to Oliver North, stonewalls other questions with an icy demeanor.

Prodded, he adds, “When a gallery buys and sells pictures, I don’t think it should be news because it’s not good for business. This is a business that does best in an atmosphere of secrecy and confidentiality. That’s really paramount.”

It is no coincidence that Newhouse and Saatchi, two of Gagosian’s best clients, are famous for their aversion to the press. Gagosian performs well in the role of the tight-lipped gatekeeper. The dearth of first-hand information about how Gagosian runs his business feeds the rumor mill that his operation must be in trouble, rumors that he denies.

During the late ’80s, Gagosian solidified his position as kingmaker of high-end art resales, topped off by the opening of his luxurious Madison Avenue gallery in 1989.

The same year he joined forces with Leo Castelli in a pristine SoHo space, simply named 65 Thompson. The unlikely duo of the brash California arriviste and the gentlemanly European would mount shows and share commissions.

With Gagosian mum on the subject of his now-legendary dealmaking, how do others describe what it’s like negotiating with him?

“It’s tough. You have to work for it. He nickels and dimes you,” said Richard L. Weisman, a Seattle collector and private investor. He sold Gagosian his art collection of more than 50 modern, abstract expressionist and Pop Art works (from Pablo Picasso to Andy Warhol) in late 1989 for “something in the range of $40 million to $50 million. … We hammered on each other.”

Asked why he chose Gagosian over a number of other competitors, Weisman said, “If you put something like this in front of Larry, he’s not going to let it go.”

The transaction wasn’t all that simple, since the art works were the exclusive assets of Lerand Inc., a closely held corporation set up by Weisman. The dealer, with his partners, wound up buying all of its shares.

Gagosian acquired the trove in partnership with Peter Brant, a real estate developer and newsprint executive, and Thomas Ammann, a prominent Zurich art dealer. It is common art world practice for dealers to join forces and buy pictures together.

Despite the accolades from prominent and wealthy collectors on the talent, loyalty and industry of Gagosian, a day does not go by in the gossip-stroked art industry without a new or used Gagosian rumor, the grimmer the better.

Everyone, it seems, wants to know how Gagosian does it, given the still-bearish conditions of the art market and the resulting downsized prices.

Gagosian shrugs at the question. “If you bunt the ball all the time, everybody is your friend, but if you swing a littler harder. …” The uncompleted sentence hovers in mid-air and then changes course.

“I’m a big boy,” said the dealer. “If the alternative is that you have to have a kind of nothing business so people can say, `Oh, he’s a good guy,’ that’s a trade-off I’m willing to take. I accept that. It’s more about the way people think than the nature of my business.”

At least part of Gagosian’s art acquisitions and dealmaking is financed by bank loans secured by millions of dollars worth of art, according to information gleaned from computerized New York City records on Uniform Commercial Code debtors.

Lichtenstein’s Pop masterpiece, “Blonde Waiting” from 1964, one of the major paintings from the Weisman transactions, is just one of the collateralized art works controlled by Chemical Bank. Chemical holds at least a dozen liens on the dealer, according to city records.

Sotheby’s Financial Services, a subsidiary of the giant auction house, also has a security interest in a number of Gagosian paintings, including Andy Warhol’s “Elvis 49 Times” and Brice Marden’s “Dylan-Katrina.”

The Lichtenstein, for example, was valued in 1989 at $4 million, according to Weisman. Banks typically loan half of the collateral value, according to one art dealer familiar with the process.

Many art galleries, overextended with interest-sucking inventory, went belly-up after the market turned south in the second half of 1990. Many in the art world mistakenly believed Gagosian would be an early casualty, that his carefully constructed but over-leveraged house of mirrors would shatter.

“I’ve never had a loan for operations,” said Gagosian, “I’ve never borrowed money for the gallery. Sometimes you use a bank to buy a painting. At times it’s the best route and it’s better than having a partner. Borrowing money for a short-term situation is a cheaper partner than somebody who’s going to get 50 percent of the upside.”

All-out Exhibits

All-Out Exhibits Gagosian’s “program,” as he likes to describe his operation, includes museum-quality exhibitions of famous artists, both living and dead, complete with scholarly catalogues and copious amounts of newspaper and art magazine advertising. The majority of works are usually on loan from prestigious private collections and museums with perhaps one choice work available for resale.

Spurred in part by the decline of the secondary market and a desire to challenge primary dealers such as Mary Boone in SoHo and Pace on 57th Street, Gagosian recently established a stable of relatively young “primary” artists, such as Francesco Clemente, Peter Halley, David Salle and Philip Taaffe, who made their reputations and fortunes in the ’80s.

“Conceptually, I like the idea of going to an artist’s studio in the morning and selling an impressionist picture in the afternoon,” said Gagosian.

“Our activity in the secondary market provides capital that helps the younger artists we represent and opens up more avenues to collectors. It puts the younger artists in a different kind of context.”

Controversy stubbornly shadows Gagosian’s quest for recognition as a primary dealer. When Peter Halley bolted from the Sonnabend Gallery in February 1992, less than three months before his scheduled solo show there, and joined the Gagosian stable, Sonnabend filed a multimillion-dollar suit against Halley for a claimed breach of contract and Gagosian for “tortiously interfering” and for “injuring Sonnabend’s advantageous business relations.” Both Halley and Gagosian denied the claims and moved to dismiss the suit.

Sonnabend unsuccessfully petitioned the court to stop Halley’s May 1992 exhibition at Gagosian’s sleek new SoHo space on Wooster Street, formerly a truckers’ garage.

According to documents filed in the suit, Gagosian sold 10 Halley paintings for $75,000 each. The Whitney Museum of American Art acquired a larger two-panel work for $150,000. Sonnabend wanted commissions on all the sales.

Sonnabend claimed Halley had been enticed to leave with a “one- time $2 million cash bonus and other extraordinary benefits,” according to court papers. He had been on a $40,000 a month stipend against future sales at the Sonnabend gallery.

“As a matter of record, we didn’t give him one dollar of advance or bonus or anything,” responded Gagosian. “I was kind of shocked that it’s gone the way it has.”

“Obviously, Halley didn’t go to Gagosian to get less,” countered Daniel Shapiro, Sonnabend’s attorney.

After the court refused to dismiss Sonnabend’s lawsuit, the parties settled this spring for undisclosed terms.

“It’s all over,” said Shapiro. “I know Sonnabend is happy with the settlement. Everybody is satisfied.”

Two Stars, or One?

Two Stars, or One? The next challenge for Gagosian, some say, is to succeed Leo Castelli as the art world’s top gun once the 85-year- old doyen departs the scene. Castelli’s retirement would leaving his two main stars, Johns and Lichtenstein, in search of a gallery.

“They’re the two greatest living artists and I would be disingenuous if I told you that I wasn’t interested,” responds Gagosian. But, he notes, editing his remarks as quickly as he utters them, “They’re Leo’s artists, and to speculate on that is just not my way.”

Queried at his SoHo gallery, the impeccably tailored Castelli adjusted a cuff of his double-breasted suit jacket and said, “What will the artists do `when I sort of leave the scene’? Well, artists like Johns and Lichtenstein won’t mind staying with Susan {Susan Brundage, Castelli’s veteran director}. I think the gallery could continue for quite a while.”

Asked to compare himself with Gagosian, Castelli chuckled and said, “I always worked with my own money. … I’m a very bad salesman and Larry is a very good salesman. But of course, he wouldn’t be as scrupulous as I am in advising one of his clients not to buy a painting because it’s not good enough for them. He also knows how to deal with very rich people, which I don’t.”

Castelli went on to describe Gagosian as possessing “incredibly good judgment about what’s good and what’s important,” attributes repeated by a number of Gagosian’s business peers.

Despite the awkwardness created by the Sonnabend suit (Ileana Sonnabend is Castelli’s former wife), Gagosian and Castelli remain closely intertwined. Castelli recently sold a vintage Johns work from his private collection, “Target with Plaster Cast” (1955), to Geffen for a price believed to be in excess of $10 million.

Castelli bought the work out of Johns’s first solo show at his gallery in 1958 for $1,200.

This time around though, it was Gagosian who introduced Castelli to Geffen, the reversal of a long pattern.

The essential Gagosian surfaces when a phone call interrupts the interview and Gagosian is told the fire department is downstairs and the building has to be evacuated. Quickly scanning the walls, covered by great paintings of 20th-century masters such as Willem de Kooning and Georgia O’Keeffe, the dealer decides he isn’t leaving – fire or no fire.

“I’ll go out on the terrace if it gets too bad,” he said. It turns out to be a false alarm.

Judd Tully is a New York freelance writer who writes often about the art market for The Washington Post.