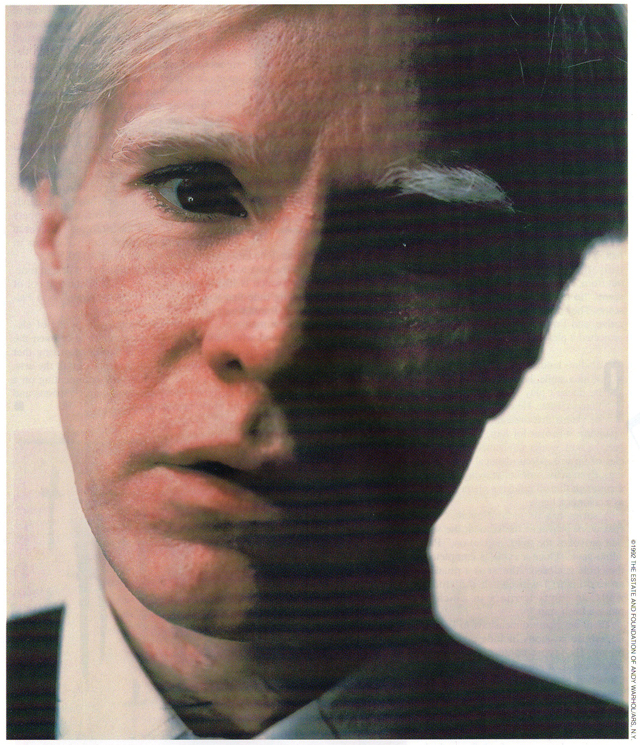

A 1979 Polaroid self-portrait by Andy Warhol. A year after his death at age 58 in 1987, his belongings sold for $23 million at auction, benefiting the foundation he set up in his will.

Five years after Andy Warhol’s death, his estate exercises tight control of his work. But problems and questions continue to emerge.

IN EARLY 1988 A collector couple purchased a ca. 1964 self-portrait by Andy Warhol for a seeming steal—$22,000. Santa Monica dealer Michael Kohn agreed to oversee the paperwork to authenticate the painting, which his clients had bought at the Abell Auction Company in Los Angeles. He sent the piece to the Warhol Studio in New York, where the offices of the artist’s estate and foundation are based. In December 1989 the estate offered to buy the piece for $22,000 “to examine it further.” But those ne-gotiations broke down. “The deal went nowhere,” Kohn recalls.

Almost a year later the estate sent Kohn a letter. “The Estate is not able at this time to form an opinion as to whether said work is, or is not, a work created by Andy Warhol,” it said. “The Estate cannot determine whether Andy Warhol directly participated in its creation, or authorized a third party on his behalf to create the work using Andy Warhol’s silkscreen or acetate, or whether the third party did so without such authorization.”

“The picture is dead in the water without their opinion,” says Kohn. “My clients can’t sell it or even give it away.”

On the fifth anniversary of Warhol’s death, the resale market for his paintings and prints—driven sky high during the speculative frenzy of the late ’80s—has been eroded by deflation and compromised by persist-ing problems of fakes. However, another problem—that of apparently genuine works languishing in art-market limbo—has also arisen because of the power the artist’s estate wields over the authentication process.

There is good reason to be vigilant, says Lucy Mitchell-Innes, senior vice president of Sotheby’s contemporary paintings department in New York. “We’re seeing an increasing number of Warhol fakes coming through the marketplace and they’re not necessarily recently made fakes, but ones made during his lifetime. The real problem is in the lack of expertise, the lack of real knowledge out there. Even Warhol couldn’t spot his own fake paintings.”

“Andy used to flippantly say, ‘Anybody can do my work,’ ” recalls Ronnie Cutrone, a New York artist who was Warhol’s assistant from 1972 to ’82. “The truth was some people really could.”

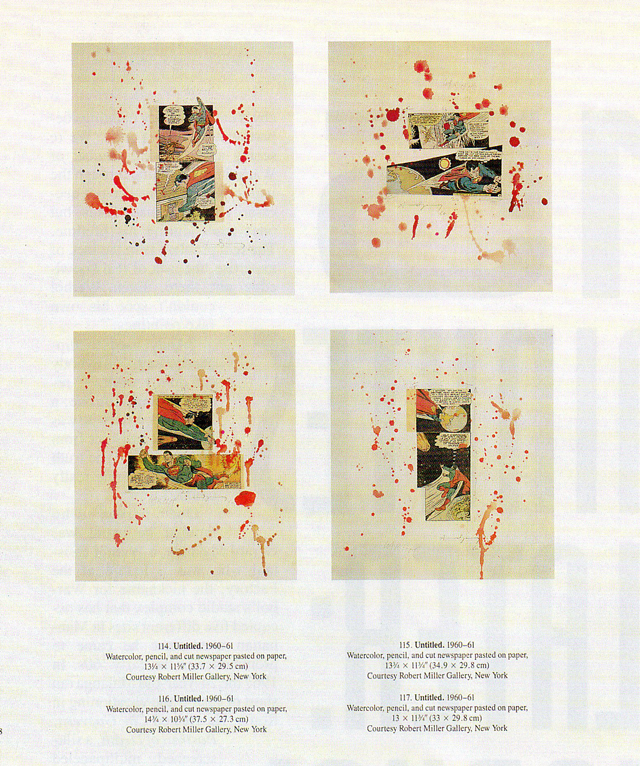

A page from the catalog of Warhol’s 1989 show at the MOMA shows four of seven collages that turned out to be fakes.

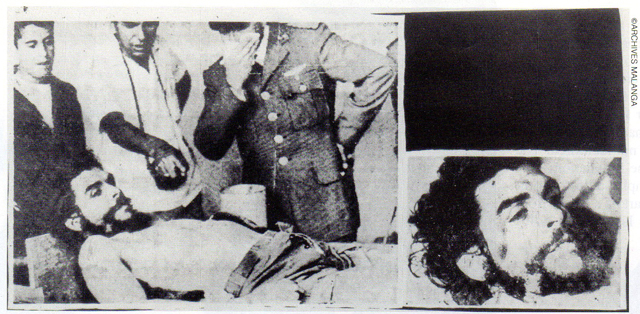

One person who thought he could was Gerard Malanga, a Warhol assistant who was a fixture at the Factory, the nickname for Warhol’s studio complex that has occupied five different sites in Manhattan ever since he came to prominence in the early ’60s. In 1967 the 24-year-old Malanga ran short of cash while vacationing in Rome. He created Che Guevera, Portrait ofDeath, a silk-screened, multipaneled newspaper photo image of the slain Cuban revo-lutionary, and signed Warhol’s name on the back. “It was exactly how Andy would have done it,” he says. “A real death/disaster painting.” (Malanga also claims authorship of an-other version, priced at $3,500, as well as a signed edition of 26 Che prints, numbered A through Z. He says they were exhibited by a Rome dealer—whose name he cannot recall—who sold the prints.) But the project backfired. The story leaked out, the dealer discovered the hoax, and Malanga barely es-caped the clutches of Interpol.

Even Leo Castelli, Warhol’s longtime SoHo dealer, was taken in. “I took it for granted it was done by Andy,” Castelli recalls. “I thought it was an interesting subject Andy would choose.” However, he adds, he never had the works in his gallery. And according to Victor Bockris, Warhol confidant and author of The Life and Death of Andy Warhol, “The paintings have never shown up on the market.”

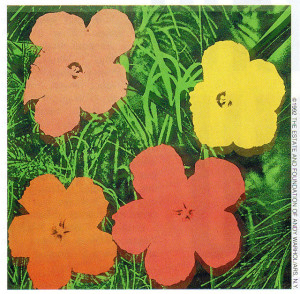

Flowers, 1966, one of about 900 pieces Warhol made of the subject. They are his most commonly faked works.

Art collector Stuart Pivar, Warhol’s close friend and constant shopping companion, says the artist considered fakes of his work “the sincerest form of flattery.” But Warhol complained about them in print. In a May 1978 dictated passage from the posthumously published The Andy War-hol Diaries, he describes an episode in which Armand Arman, the French Nouveau Realiste artist, “called and said he’d sold eight ‘Flower’ fakes of mine, because, he said, he didn’t know they were fakes. But I said, ‘You must have known or you wouldn’t have hid them away for all these years, and you must have bought them cheap off somebody’ . . . They made my prices go down because people are now afraid to buy paintings because they feel they could be buying fakes.”

But Arman disputes Warhol’s recollection. “There were perhaps four flower paintings. I got them from one of Andy’s former assistants, who told me he needed the money. There were at least two or three assistants who were authorized to sign his name. I didn’t have a chance to keep them a long time because I called up Andy right away and when he didn’t want to endorse them, I returned them. Except for the flowers, he always resigned or authenticated everything I showed him.” Arman declined to identify the assistant but said it wasn’t Malanga. He did not recall exactly how much he spent on the works, saying only that the sum was in the “thousands.”

Shortly after Warhol’s death, his prices began to soar. In a May 1987 auction at Christie’s New York, the painting White Car Crash 19 Times made a record $660,000. It sold to Zurich dealer and collector Thomas Ammann (who is preparing the artist’s long-awaited catalogue raisonne for paintings). The sum eclipsed the previous record of $385,000 for the painting 200 One Dollar Bills, set in November 1986 at Sotheby’s.

Che Guevera, Portrait of Death (detail), a “Warhol” created by Warhol’s assistant Gerard Malanga in 1967.

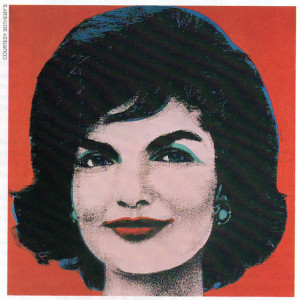

In May 1989—at the height of the art boom—Shot Red Marilyn (1964), a silk-screened canvas that once belonged to Robert Rauschenberg, doubled its high estimate and fetched a record $4.07 million at Christie’s. That same month at Sotheby’s, another Warhol icon, Red Jackie (1963), made $825,000. It subsequently changed hands many times, selling for as much as $2.2 million, according to an American private dealer who declined to be identified. But when the market dropped, Warhol’s prices, like everything else, shrank. Last November the same picture returned to the auction block, again at Sotheby’s, and sold for $352,000 to Ammann, a price he describes as “dirt cheap.” In both auctions the presale estimates were identical—$300,000 to $350,000.

Warhol and Malanga at the Factory, Warhol’s New York studio, ca. 1964

In November 1989 at Christie’s, “Marilyn,” the 1967 set of ten screenprints in color published by Factory Additions, reached $506,000. At the same sale, a single image of Marilyn from the same edition of 250 realized $44,000. A year later at Sotheby’s, an identical Marilyn from the same edition sold for $13,200, representing a 70 percent drop. Some of the highest-priced Warhols in today’s market are his “Disaster” series (1962-1964): of car crashes, race riots, and suicides, especially those executed with multiple images and panels. “I sold a couple of them for over $5 million,” says Manhattan dealer Larry Gagosian. Ammann confirms Gagosian’s claim. “It’s absolutely true,” he says. Amman says that he sold a multiple-image White Car Crash to a Japanese collector in 1990 for $3.8 million.

According to Gagosian, a single-panel “Disaster”—if available—would fetch $2 million to $3 million in the current market. “Practically all of them are in museum collections at this point,” says David Bourdon, author of Warhol, a biographical and critical study of the artist. The reason, he says, is that the “Disasters” are “the most important of all his works. Lots of other artists have dealt in horrific subject matter but none so topically and matter-of-factly as Warhol.” Ironically, Warhol’s first dealer, Eleanor Ward of New York’s Stable Gallery, refused to show the series in 1965, prompting Warhol to leave the gallery.

Warhol died at age 58 in February 1987 following gall bladder surgery at New York Hospital. A multimillion-dollar medical malpractice and wrongful death suit in Manhattan Supreme Court initiated by his estate and his two brothers, John and Paul Warhola of Pittsburgh, was settled out of court last December for a substantial sum. The settlement, which included a secrecy provision, “was fair and equitable to all parties , ” says Steven M. Hayes of Parcher and Hayes, who are the lead attorneys representing the estate.

For years there have been rumors of the chaos and removal of art that reputedly reigned at the Factory after Warhol ‘S death. Frederick W. Hughes, Warhol’s business manager who be-came the estate’s executor, disputes those stories. “I did my best as executor to make sure there was no funny business going on. I hate to sound like Mildred Honesty but it was all so cut and dried. We have a very important partner, the attorney general of the state of New York. There can’t be much fooling around.”

The 1982 will Warhol left behind provided Hughes, who now suffers from multiple sclerosis and is confined to a wheelchair, with $250,000 (exceeded only by $719,396 to John Warhola and $584,743 to Paul Warhola). The will instructed Hughes to set up a foundation “to benefit the visual arts,” directed by Hughes, Warhol’s brother John, and Vincent Fremont, executive manager of the Warhol estate as well as the exclusive agent for any sales of Warhol works from the foundation and licensing agreements. The bulk of Warhol’s estate was left to the foundation. As of April 30, 1991, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., had received $103,283,410 from the estate. Warhol’s art represents $82.9 million of that figure. The foundation offices occupy Warhol’s last studio address, a former power plant on East 33rd Street.

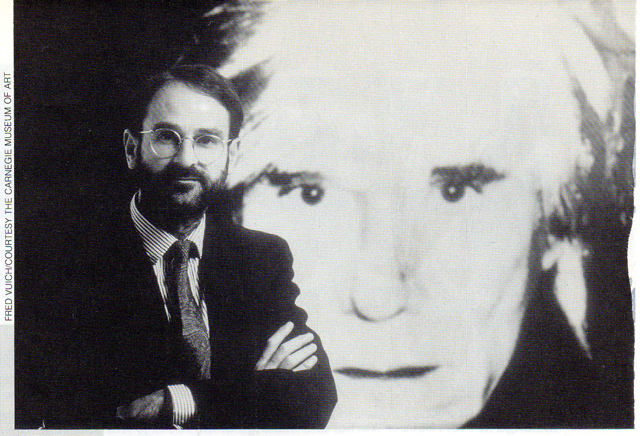

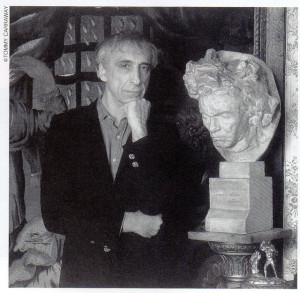

Mark Francis (with Warhol’s Self-portrait, 1986) will direct the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh

One enormous chunk of the legacy—just over $23 million–came from Sotheby’s ten-day sale in April 1988 of Warhol’s art, furniture, and objects that crammed his Manhattan townhouse on East 66th Street. The building sold last summer for a reported $3 million. Warhol had purchased it in 1974 for $310,000. The buyer was not identified. The proceeds also benefited the foundation.

Warhol’s real estate empire didn’t stop in Manhattan. He also left part of a beach front estate in Montauk, Long Island, and a 40-acre parcel of undeveloped land near Aspen, Colorado. As one close associate put it, “Warhol was an extremely, extremely rich man. He and Fred [Hughes] managed their investments brilliantly.” Among the Warhol securities already benefiting the foundation are $498,450 in Campbell’s Soup Company bonds.

Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Christie’s appraised Warhol’s paintings from the estate in 1987 and recently appraised the same huge group for their fair market value to coincide with the paintings being transferred and “gifted” from the estate to the foundation. Martha Baer, director of 20th-century fine arts at Christie’s New York, said she could not reveal those figures, but the “fair market value” was pegged at $82.9 million as of April 30, 1991. (The figures do not as yet represent the artist’s drawings and works on paper currently being appraised by Christie’s.)

An independent audit, by the New York accounting firm Pannell Kerr Forster, did not state how many paintings comprised Christie’s appraisal. No one contacted at the foundation would say or even estimate the number of artworks in their possession. The foundation has rented an off-site warehouse to store the Warhol collection at a cost of over $16,000 per month, according to the auditor’s report.

Archibald L. Gillies, president of the foundation and former head of the World Policy Institute, says that the next audit of the foundation, which will come out this fall, will reflect the appraised addition of drawings, prints, and photo-graphs. The current figure of $82.9 million for paintings, sculpture, and collaborative works (made with artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring) would not be substantially larger, Gillies says.

Edward W. Hayes, counsel for the estate (on whom Tom Wolfe based his character Tom Killian in Bonfire of the Vanities), says that the “overwhelming majority” of the estate’s assets have already been transferred to the foundation. How much money the foundation will ultimately receive “is not something I can comment on,” says Hayes. The figure of $224 million worth of Warhol artworks was listed in the estate’s federal estate tax return filed in June of last year, but those now highly inflated numbers were based on appraisals completed at the height of the art boom.

As of January, the foundation had awarded 421 monetary grants totaling $12,028,000 to nonprofit cultural organiza-tions both in the U.S. and abroad. The grants range from $50,000 for the recent “Dislocations” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art to $25,000 to restore the garden at Edith Wharton’s country home in Lenox, Massachusetts. Some of the largest grants have gone to the New York Academy of Art, a traditional, European-style school that emphasizes drawing. Warhol was a founding member of the academy’s board of directors; Stuart Pivar is chairman emeritus. The academy has so far received $1.1 million.

“That education grant is not reflective of where we’re going in the future,” says Pamela Clapp, the foundation’s associate director of programs. “We’re looking for pro-grams with a greater potential for far-reaching effects.”

“I think the foundation will be more interested in affecting new ideas in the art world,” says Agnes Gund, a foundation board member who is also MoMA’s board president. “And giving grants that may affect political issues such as AIDS and art. Corporations are very wary of funding anything really contemporary.”

Asked how long the foundation intends to stay in business, Gillies said, “It’s open-ended, the plan is to keep going.” Peter P. McN. Gates, attorney and secretary for the foundation, explains that “the theory is, the foundation will eventually convert its assets to cash over the long, long haul, and give away millions and millions of dollars every year to the art world.”

The Warhol Foundation and the Dia Art Foundation formally agreed in October 1989 to gradually give over 750 paintings (roughly 700 from the Warhol Foundation and 60 from Dia) to set up a major Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh under the administrative and financial aegis of the Carnegie Museum of Art. “They have to finish the museum all out of their own pocket and raise enough of an endow-ment to carry the thing,” says Gates. But the Warhol Foundation is digging in its own pockets to help launch the museum with grants that so far have totaled $1.1 million.

“It’s not just a gift but a joint venture between Dia, the foundation, and the Carnegie Museum,” explains Dia Foundation director Charles Wright. “The contribution is very conditional. If there’s ever any breach, the paintings all come back to Dia.” Wright said Dia originally had the idea for the museum but was unable to raise the funds. “It’s a perpetual obligation,” he adds.

“The paintings can never be sold or used for any purpose other than to contribute to the definitive program of the museum.” He estimates the value of Dia’s and the estate’s art pegged for Pittsburgh at “easily over $100 million.”

Aside from the unprecedented cache of paintings, prints, drawings, and sculptural works, the museum’s holdings will include films and videos from every decade of Warhol’s career plus an extensive archive from the Warhol and Dia Foundations. Wright calls the Dia Warhols “classical” and “masterpieces,” including six “Disasters.” The paintings, to be phased in over a nine-year period, will begin to be “physically transferred” to Pittsburgh in the summer of next year.

The seven-story museum will be fashioned out of a renovated warehouse building by architect Richard Gluckman. It is scheduled to open next January under the directorship of Mark Francis, the highly regarded British curator of contemporary art at the Carnegie Museum of Art and formerly a curator at the Pompidou Center in Paris.

At present the museum has received one painting from the Warhol Foundation, a giant and previously unexhibited Elvis (Eleven Times) from 1963. The foundation appraised the donation at $5 million in its 1989 IRS return. As of April 30 of last year, the foundation realized $200,000 from the sale of artworks, according to its auditor’s report. Commissions on those sales totaled $20,000.

The foundation has been choosy about whom it sells to, limiting its clients to top-drawer institutions and private collectors. Last December, for example, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles acquired its first Warhols from the foundation— Telephone (1961) and Old Fashioned Telephone, a related graphite sketch. The undisclosed pur-chase price was provided by an anonymous donor.

Fremont resigned his post as secretary of the foundation’s board of directors in December 1990, when Gillies was elected president and Agnes Gund and writer Brendan Gill joined the board. A year later Kathy Halbreich, director of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and Kinshasha Holman Conwill, executive director of the Studio Museum in Harlem, were added. When Fremont resigned, chairman Hughes lost his closest ally as well as some of his power, according to friends of both men.

Warhol’s Red Jackie, 1963, has sold for as much as $2.2 million dollars. Last year it reached only $352,000, a price it’s buyer called “dirt cheap”

“It’s not a blood feud,” Gund says. “It’s all going to be worked out. I don’t think it will bring down the foundation because it’s already much stronger than any one person.”

Since Warhol’s death, the estate has become the official arbiter in authenticating Warhols—the stamp of approval that makes a “Jackie” or “Mao” or “Elvis” eminently marketable or practically worthless. (The service is free of charge.) In mid-1990 it began passing on its verdicts through letters, written on the Andy Warhol Studio letterhead and initialed by an authorized representative of the estate (usually Fremont). “One letter states it is a work by Andy Warhol, another letter states that in our opinion we do not believe it’s a work by Andy Warhol, and a third is, we can’t come to an opinion at this time,” Fremont explains. “It’s also possible that at some future date an opinion can be changed if something comes to light and sways us in a different way.” He has never changed an opinion, he adds.

Fremont would not reveal the number of letters issued or comment on works that went through the authentication process. Nor would he reveal the specifics of the process—”to do so would be to provide a manual for forgers.” He did say the estate has employed handwriting experts for help in authenticating signatures. He also said that other members of the authentication team include former Factory assistant Jay Shriver and foundation curator Tim Hunt.

“I just assumed they were fine,” recalls Charles Stuckey, a Warhol expert and curator of 20th-century painting and sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago. Stuckey had viewed the collages by chance at Miller in 1988, around the time McShine chose them for the show. “The foundation didn’t have their act together then,” he explains, adding that he thinks it is run more professionally now. “Kynaston started organizing the show just weeks after Warhol’s death and they were still obviously disorganized by institutional standards. It was still run as if Andy was there. Suddenly they had quite a different mandate than what they were used to. It was a kind of overwhelming situation. Kynaston came across the collages late in the game. He was in a scoop situation. To exclude them was to miss the chance.”

The foundation was not really involved, according to Fremont. “I’m not going to point a finger at anybody on this one,” he says. The collages, he says, “were seen by people here, but I really didn’t see them.” (He declined to say who did.) “But there was no official opinion given—no one brought in anything to be authenticated. Everybody felt they were genuine because it was an unusual thing to try to be forged.”

In October 1989 another group of Superman comic book collages, which Stavitsky describes as –identi-cal” in style to those at MoMA, showed up at a Binoche et Godeau auction in Paris. Paolo Dal Bosco, an Italian dealer, bought four of them for $63,800. Several months later, first Binoche and then Dal Bosco received letters from the Warhol estate, which said that the collages were fakes. Dal Bosco brought the auctioneers to court, which did not admit the estate’s letter as evidence. The case is still pending.

As the estate became more experienced in authenti-cating artworks, it also got tougher. “The process has become more protective for everybody involved, both for the estate and those people bringing work in,” says Fremont. “It’s a learning process and it becomes gradually stricter as the procedures become more defined. It’s not an easy thing. Certain pieces can take months, if not years, to get through the authentication process. Others take a matter of scrutinizing in an afternoon.”

Dealer Michael Kohn says that although the estate refused to come to a decision on the Warhol self-portrait his clients bought, two other virtually identical and unsigned Warhol self-portraits from the same silk screen/photograph sold in November 1987 at Christie’s and Sotheby’s for $28,600 and $29,700, respectively. According to the catalogue entry, the Sotheby’s Warhol bore a Frederick Hughes authentication stamp and is slated for inclusion in Ammann’s catalogue raisonne. “I must have been the experiment the estate was conducting, as they were forming a policy of becoming stricter,” Kohn says.

Art collector Stuart Pivar is chairman emeritus of the New York Academy of Art, which has received $1.1 million from the Warhol foundation

There are several other issues involving the Warhol estate. His name is a trademarked commodity and images from his paintings and illustrations have been used to decorate shopping bags, calendars, note cards, and appoint-ment books. All of these “authorized by the foundation” endeavors enrich the estate/foundation, including a recent “well into the six-figures” deal with Shiseido, a leading Japanese cosmetics company, for the use of a ’50s Warhol illustration of an angel for their new perfume, Angelique, according to Paul Hanley, a law partner in Coblence and Warner and litigating attorney for the estate.

The estate has also been embroiled in expensive breach of contract litigation on a number of legal fronts over the use of Warhol’s name. Two related suits, filed by the same company, are still pending in federal court. Hanley explains that they stem from a major licensing agreement dating from November 1987 between the estate and the Atlanta-based Schlaifer Nance and Company (marketers of Cabbage Patch Kids). Schlaifer Nance had asked for $40 million in damages over proposed fashion-related items, including T-shirts, sweaters, neckties, and a line of sportswear using the Warhol name that were vetoed as inappropriate by Frederick Hughes. That agreement—” except for the outstanding issues being litigat-ed”—is terminated, according to Hanley. After hearings, the American Arbitration Association in Atlanta determined that the estate’s vetoes were made on unreasonable grounds, awarding Schlaifer Nance $4.1 million in damages.

Questions surrounding the reach of Schlaifer Nance’s control of the Warhol name have also delayed the publication of the completed first two volumes in Ammann’s long-awaited catalogue raisonne of Warhol’s paintings, according to a knowledgeable source who insisted on anonymity. “There’s a mess at the foundation at the moment,” the source explains, because of the licensing of Warhol’s name. “It’s a legal problem, so much so that the publisher [Munich-based Schirmer Mosel] wants absolute assurance that they cannot be sued.”

“No, no, no, that’s a separate issue,” counters Gillies. “It’s more a question of the right way for the catalogue raisonne to be done. A lot has happened since Warhol chose Ammann to do it. That was before the advent of the museum in Pittsburgh.”

Meanwhile, says Peter P. McN. Gates, attorney and secretary for the foundation, potential purchasers of Warhols should know that the market is in no danger of being glutted. “The foundation’s got a lot of art,” he notes. “It’s important for the art market to know that it’s not going to run out of cash and dump huge quantities of Warhols on the market.”