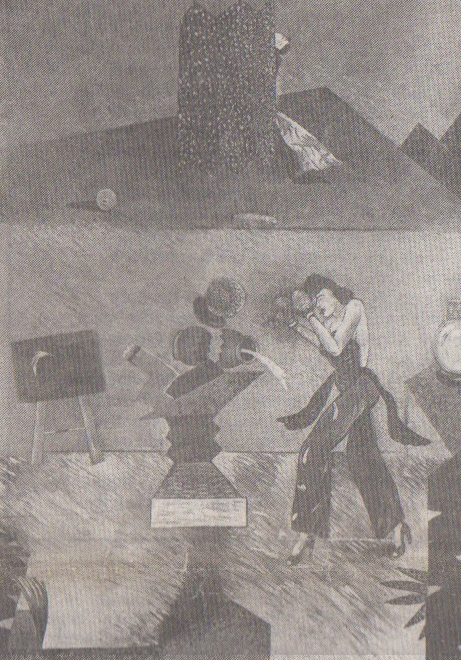

PHYLLIS BRAMSON, ‘Personal Values—Toward Pleasure,’ oil, acrylic, collage on paper, 41″ x 29″, 1981. Photo courtesy Dart Gallery.

In a move vaguely akin to manifest destiny, art world style, increasing numbers of New York art dealers are raiding the fertile homesteads of Windy City artists. Just as this phenomenon has gained momentum, the exact reverse is occurring in Chicago lofts and storefronts, as artists pack their bags and head for Midway Airport, bound for the promise of gold-paved streets in Manhattan.

A quick flip through the pages of any New York gallery guide reveals an impressive smattering of Chicago artists showing at prestigious salons on 57th Street, West Broadway, and Madison Avenue. Names that just, a season or two ago were restricted to the byways of West Hubbard Street are strutting high in Manhattan. Hollis Sigler and John Obuck at Barbara Gladstone’s, Seymour Rosofsky and Phyllis Bramson at Monique Knowlton’s. And, as most everyone knows, a stable full of veteran Imagists at Phyllis Kind’s in Sollo.

With savvy New York dealers talent-scouting at out-of-the-way oases like Nancy Lurie Gallery in Chicago, the thirst for acquiring Chicago art will hit the cliffs of Dover rather sooner than the arrival of Birnam Wood at Dunsinane. With an international clamor for what Patterson Sims (associate curator of the permanent collection at the Whitney Museum of American Art) calls “quasi-surreal narrative figuration,” it behooves the curious to examine the reasons for this abnormally high pulse-rate.

Peter Schjeldahl, senior art critic for the Village Voice and long-time purveyor of cultural syrup for the monthly art magazines, says, “Once there was a distinct and obvious difference in taste between Chicago and New York art. There’s a blur now. The New York resistance to the expressionist impulse has weakened, if not collapsed, and Chicago has the tradition that New York needs for that impulse. The tendencies in recent art—not just New York—is to revive expressionism and revitalize the use of the figure. Naturally, this gives

Chicago-type art an interest it didn’t Use to have. So now, those crazy, expressionistic impulses give artists in New York an opportunity to get those influences in a native form, since it has already been processed by Chicago. I don’t know how long this will last. The break, no doubt, wit have to re-appear.”

Uptown at the Whitney, Sims described the laborious process of filtering American art through the cheese cloth of the Biennial. Brainstorming and crisscrossing the continent since the day the last biennial opened, Sims and curators Barbara Haskell and Richard Marshall found “quasi-surreal narrative figuration” the most prevalent form of art. The quasi-surreal surfaced in Fort Worth as well as Chicago, Albuquerque and even North Carolina. The quasi-surreal room at the Whitney included the works of Chicagoans Ed Paschke and Hollis Sigler, of Russ Warren (North Carolina), Richard Shaw (California), Louisa Chase (New York), and Richard Thompson (New Mexico). “For us,” Sims opined, “that room represented the most national character. Chicago art has becomed nationalized. It was the room that visitors picked out as the most repugnant, or, at least, the one that aggravated people a great deal.”

Sims was so intoxicated with the quasi-surreal tattoo that at a recent performance of Parade at the Metropolitan Opera, designed and costumed by David Hockney (the drawings are currently on view at Andre Emmerich Gallery), he could have sworn that Hockney had been influenced by Hollis Sigler. Sims chuckled at the absurd recollection and sped on to talk about maximalism.

ED PASCHKE, “Tragicque,” oil on canvas, 32″ x 46″, 1980. Photo by William H. Bengtson, courtesy Phyllis Kind Gallery.

With the decline of New York as the world art capital, according to critics like Schjeldahl, and the insatiable thirst of the art market for more tenderloin, the prospects for the obscure to gain the limelight brighten. “Collectors,” Schjeldahl muses, “are being forced to develop new tastes because they’re being priced out of their old ones.”

Phyllis Kind, surfing the tidal wave of Imagist art in Chicago, New York, and the art fairs of Europe, described her plunge east. “When I came to New York in 1975 the attitude towards the work was diametrically different to the way it is looked at now. With New York artists, it was like the elevator to my gallery would open and boom, they would leave. That was the Roger Brown show in 1975. But by 1977 it was already different. In retrospect, the timing was phenomenal. The waiting list I have for Ed Paschke is one I can’t satisfy for I

don’t know how many years. And Roger Brown, who opens here April 14, his show is sold out before it gets uncrated. And still, people in Chicago ask me, `Do they really like the work in New York?’ They still don’t believe it.”

A good barometer for Chicago art fever can be read in the roster of New York dealers signing up for the expensive booths (figure on $10,000 for the five-day fair) at Navy Pier’s Chicago International Art Exposition. Unlike the schlock print fairs in New York and Washington, D.C., the Navy Pier salon is the creme de la crone of art. Bookings were so tight this year that one New York dealer, with a stable full of Biennialized photographers, had to push and shove for even miniscule space. The international art fairs are becoming direct lines for selling the quirky and the quasi. Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporaine (FIACRE) in Paris and the grandmother of them all, the June spectacular in Basel, Switzerland, are the new commodity exchanges for global art.

Monique Knowlton, an uptown dealer with a sharp eye for that awkward string of words that is changing the complexion of living room walls the world over, said, “I’m going to take a large space at FIACRE in October. I’m going to show Bramson, Lostutter,’ and Donnelly, all Chicago artists. I think people are only just beginning to realize how important Chicago has been to New York. It’s a little bit like not admitting for a long time that the surrealists were influential on the abstract expressionists. And yet it’s still hard to

ask how Chicago has been influential to New York. But somehow the images come back to painting. Chicago has had it all along. To me-it’s the most original work being done in the U. S. You can find pop art and minimalism in Europe, but you can’t follow what’s going on in Chicago. It’s very personal. They don’t really work as the cubists or the abstract expressionists did. Chicago painters are obsessive and repetitive. It’s still work one can buy. You can still buy large and important paintings by Chicago artists for less than you can from someone showing for the first time at Robert Miller Gallery.”

The conversation in Knowlton’s 71st Street gallery was cut short by an invasion of Saturday afternoon viewers, asking for and getting price lists and biographies on Phyllis Bramson. Knowlton returned to the tape recorder and continued the analysis of the Chicago-style art boom. “It’s the Chicago dealers’ fault for not raising the prices, but that is in the process of changing. Roger Brown’s work has tripled in price. For a very long time, Chicago people felt it necessary to buy things from New York. Maybe that’s why so many collectors went to

Navy Pier last year because they knew the New York dealers would be there. As an example I showed Robert Donnelly there, and several people bought his work. They had never seen it before. These Chicago collectors just hadn’t gone to Nancy Lurie where Donnelly shows. I think her gallery is just a little off the beaten track and some collectors just don’t go there. As a dealer you have to travel.”

As Knowlton pointed out, the only requirements for pushing Chicago figuration (the same strategy could be applied to marketing deep-dish pizza) would be a couple of American dealers taking booths at one of the international fairs and showing enough Chicago work. Since this is already being done at FIACRE under the gourmet category of “Nouvelles Tendances” (last year Phyllis Kind, the Willard Gallery, and Paula Cooper

championed the ‘new), Chicago is sprinting closer to a Michelin star deSignation.

If the Germans and Japanese rhapsodize, as Patterson. Sims observed, over Reginald Marsh (virtually every Marsh in the Whitney’s collection is on international loan) and Yasuo Kuniyoshi, there’s no telling what bedlam might break when Berlin and Tokyo get to see the descendants of Ivan Albright and the . There will be a bit of a wait since the current Who Chicago?, organized by Tony Knipe in cooperation with Phyllis Kind, will not travel beyond the British Isles. The vagaries of the German mark are more responsible for the huge show not hitting the continent than any flagging of interest from European museum directors.

The quirky and the quasi stick to the tongle like rare sweetbreads. The ritual cycle of solo shows in New York, a brief appearance in the Biennial, a few days of concentrated selling at one of the big art fairs, and the necessary palate-clearing sherbert in a five-dollar art magazine will orbit the Second City artist into world class citizenship. So don’t be in such a hurry to pack your bags. Gotham is already turning the corner.

JUDD TULLY is bullish on deep-dish pizza. He is fatigued of the freelance label and distinction of penning Ruckus Manhattan four publishing seasons ago.