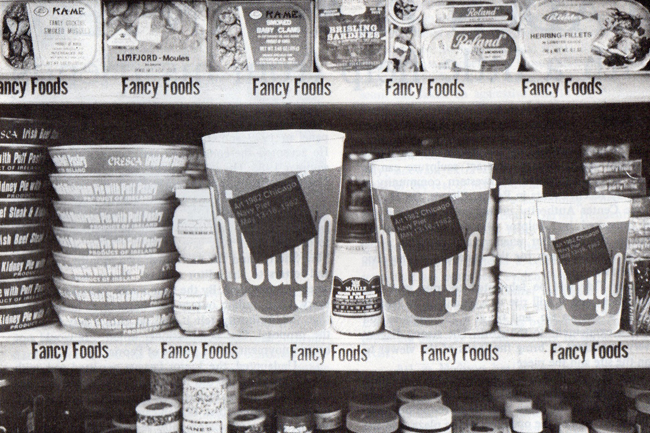

photo by Sarah Wells

Art 1982 Chicago was manna from heaven for the Museum of Contemporary Art. The opening night bene-fit bash—after all the sushi had been rolled—netted the MCA $85,000. A less fortunate soul, Parisian art dealer Alain Blondel (Booth No. 1-117), didn’t sell a single painting, his car was towed, and one of his wood sculp-tures suffered water damage from a leaking ceiling. Navy Pier lured 112 galleries hailing from Berlin to Boca Raton, drew 20,000 paid visitors ($6 general admission), and turned the lakeside landmark into a five-day fine art orgy. With dealer participation up 25% in 1982, an additional 40,000 square feet of exhibition space was allotted. Richard Solomon, president of Pace Editions, commented,

This is the first fair we’ve done, and, at this point, we don’t know how to equate the business we did at the pier with how we would have done just staying put in New York on 57th Street. The overall quality was very good. Success will be the biggest problem for the future. It’s already too arduous for somebody to come in and digest it all. The attendance was extraordinary. But we were disappointed in the number of people who were interested in buying. Opening night was a disaster. People wanted to party, and that detracted tremendous-ly from the commercial aspects. Many collectors felt they had done the fair [at the party] . That was a major miscalculation. I would hope in the future the viewing part is separated from the party part.

Set off by Pace’s optional gray carpeting (dealers stuck with fire engine red runners cringed in envy), the dazzling new edition of a Chuck Close self portrait (70″x54″) in handmade and manipulated paper, sold like hot cakes at $10,000 a shot, unframed. Dealer discounts at 30% were quickly suspended by Pace to prevent the edition of 15 from selling out.

Major league publishers with multi-booth installations. such as Pace, Tyler, Vermilion (the new kid the block), Gemini G.E.L., and Petersburg Press. stole the show in sales. Dealers without multiples to par-lay felt the cautious chill of the recession. Barbara Glad-stone. Editions enjoyed brisk sales of Jedd Garet’s new edition of three images ($1,500 each or $3,600 for the set), while Garet’s dealer in paintings and sculpture, Robert Miller, bit the canvas bullet.

At last year’s fair, Andre Emmerich sold an awning-striped, Morris Louis painting for $260,000. This year. “not withstanding the recessionary climate,” Emmerich sold the behemoth steel sculpture of Joel Perlman, Big Diamond, to Florida mega-collector, Martin Margulies. Big Diamond tickled the traffic jam of fluorescent light fixtures in the shed over “Mayor Byrne’s Mile of Sculp-ture” (organized by the newly formed Chicago Sculp-ture Society and fueled by a $100,000 “revolving fund” from the city), a free event leading into the ticket kiosks of the art fair. Big Diamond will soon reside on Grove Isle in Coral Gables.

“There is a truism about the art market,” Andre Emmerich began,

Famous collectors don’t buy much art. They already hove it. You can never sit on your fanny. There’s always a new public. A number of major sales began to be dis-cussed in Chicago. We were very pleased with the results. The print publishers do a great deal of business. In Basel, print people are in another physical space, but I’m against that ghetto mentality. European representation is just beginning. We’ll have to see if they [ such as Galerie Denise Rene Hans Meyer of Dusseldorf and Annely Juda Fine Art of London] come back and who they bring in their wake.

The influence of the Chicago art fair on the world art market is impressive in light of the fair’s infant track record. Sotheby Parke Bernet pushed its twentieth-century art auction in New York forward one week to May 20 so as not to interfere with the extravaganza in Chicago. In 1981, Sotheby was impervious to dealers’ and collectors’ hand-wrenching over the conflicting events.

“The Chicago fair,” observed Richard Solomon,

stops the print market dead in their tracks. No one was buying at auctions three to four weeks before the fair. All the dealers hold their breath to see what turns up in Chicago. For a publisher, one of the disadvantages is that it forces you to publish everything at the same time and that puts pressure and distorts the whole flow of the publishing cycle. I’m talking about a good six- to eight-month compression. There is no question that it has become absurd for American dealers to go to the Euro-pean fairs. Now it’s the Europeans’ turn to come over here and do what we did for years.

Max Protetch, a 57th Street dealer who did not renew his exhibitor status in 1982, went to the fair as an unfettered observer. “I didn’t have a booth this year for a few reasons,” Protetch explained.

I hate fairs. I find them degrading. But business was the primary reason. I opened a monstrous new gallery downtown [Max Protetch [Open Storage] , and my staff would have mutinied if I had created more work for them. Last year we made a profit but “lost” good pieces of art. We had a lousy space. The lights didn’t work part of the time. I even held out some payment. In all fair-ness though, the organization is much better this year. It’s not fun to sell great art at a fair. It’s depressing be-cause great pieces look degraded in that context.

“If art is context,” John Cheim, director of Robert Miller Gallery opined,

I think the fair is a very bad context for art. Here at the gallery I don’t feel like I’m just selling goods. I can really hang a show. But you can’t do that sort of thing at a trade fair. It’s just goods for sale. It’s really gross. I don’t think well do it next year. Sure, we sold a few things, enough to pay our hotel bill. (We stayed at a very nice one.) We thought we should participate this year to show some of our younger artists. As a result of the ex-posure, Hans Meyer of Galerie Denise Rene Hans Meyer will show Louisa Chase in Germany next year. Young Hoffman might show Jedd Garet. Dealer camaraderie is great. We spent $12,000 door to door. One never knows. We advertise a lot and never know what we get out of it.

Barbara Lloyd, director of Marlborough Fine Art (London) Ltd., a veteran of the Paris F.I.A.C. and Basel art fairs, talked a British blue streak:

We’ve been hearing about the Chicago fair for two years. The public is much more interested and knowledgeable. The organization is far superior to the European fairs. You don’t have to run around bribing people as you do in Europe. This is so exhausting. I’ve never had to talk so much. I’ve talked to more potential clients in a period of four hours here than a week at F.I.A.C.

Hilke Skulima of Galerie Folker Skulima, Berlin, kept a nervous eye on a delicate George Rickey maquette (the poor fellow had been knocked around a bit by clumsy aficionados) while commenting, “Chicago can compete with Basel this year. We’ve made a tremendous number of contacts. Isn’t that Cy Twombly ($95,000) beautiful?”

John D. Wilson, founder of the “art pier” and president of the Chicago International Art Exposition (let’s throw in one more hat, president of Lakeside Studio), remarked cheerfully,

I think we’re going to break even this year after we pay all our bills. We’re super-pleased, and I can guarantee that next year the food will be much better. That was the number-one gripe on the complaint sheet we handed out to exhibitors.

Breaking even is a great leap forward for Art 1982 Chi-cago. Last year, the ledger ran red to the tune of $80,000. In 1980, the loss was a staggering $125,000.

While Art 1982 Chicago resonates with Hertzian hubris, storm clouds of a bear market threaten the hori-zon line. (Note a mid-May, gloomy headline of the Wall Street Journal: “Art Market Remains Hurt By Recession Even At High End.”) As Allen Schwartzman, director of Barbara Gladstone Gallery, observed, “This year we did much better -wi IQ. smaller, less expensive pieces.” Karen McCready, sales dii4ctor of Crown Point Press and past director of Pace Editions, noted, “The market is cautious. They’re buying good things but carefully.” Some dealers did worse, or as Pat Hamilton of Hamilton Gallery said, “Chicago was a bust.”

On the flip-side of the Hydraian market, Monique Knowlton doubled her sales the second year in a row, offsetting two dismal months in New York. Phyllis Kind describes the event as going to “five, eight-hour Bar Mitzvahs.” With all the chatter equating the Chicago fair to Basel’s, relatively few foreign dealers or, for that matter, collectors, have ventured to the Wihdy City for May Day ,while Andre Emmerich is the only “American” painting dealer (not counting his outpost in Zurich) who has reserved space at the June fair in Basel.

What bodes in ’83? Better hotdogs? Hotter coffee? Certainly, booth rentals will be higher. The thorough-bred selection committee will shoehorn more prestigious New York and European galleries into the demographic melting pot of the art casbah. Incumbent committee-person Bob Munk, director of Castelli Graphics, pines for Metro Pictures and Paula Cooper Gallery of New York to take the plunge. It looks bad for the little guy in Grand Rapids. It always has.

The rough house complexion of Navy Pier is about to undergo a radical face-lift. Just nine days after the Andy Frain boys frisked their last art pier visitor, the City of Chicago and the Rouse Company of Columbia, Maryland (an “urban revitalization” outfit) signed a letter of agreement calling for a $277 million, lakefront, festival- and tourist-complex, comprising 200,000 square feet of retail space; 100,000 of the same for entertain-ment; a 450-room, first-class hotel; a parking garage, and a public museum and art center. And don’t forget the 400-slip marina.

Rouse will ante up $217 million, with the city pro-viding $60 million in sewer and road construction costs. 1986 is the target opening. For those buffs who have imbibed the Big Brother Rouse delights of Boston’s Faneuil Hall marketplace or the demolition derby now underway in Manhattan’s South Street Seaport, the fu-ture of Navy Pier posits a question mark larger than an Oldenburg monument.

The Lakeside Group has received assurances from the city that Navy Pier is all theirs for the week prior to Memorial Day 1983. But before a plaque is fabricated to mythicize the fair and gondoliers are imported from Venice to steer and serenade biennale fervor, Chicago style, a bearish growl from the recessioned marketplace is in order.

JUDD TULL Y, New York freelancer, hopes Art 1983 Chicago (in honor of the city’s sesquicentennial) will offer fine art golf carts to fatigued foot soldiers.