A cultural blitzkrieg has hit these shores bearing the stretched-canvas flags of Germany and Italy. America, precisely the New York art world, has embraced the phenomenon generically tagged “new expressionism.” The paintings are big, the colors are brash, and the images are wild with hubris.

Even the casual art buff has heard of, and perhaps seen, the urban surrealism of the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978) and the neon-glow figures of the German expressionist E. L. Kirchner (1880-1938). Melding the style and bravura of these two European titans triggers the horsepower of the new European expressionism.

Not since the advent of abstract expressionism (in some ways the new European expressionism mimes Jackson Pollock’s bad-boy persona) on the heels of World War II, has an art movement monopolized the media and fed the art public such kinky fare. Much of the work exudes a primitive scent, yet the canvases erupt with visual footnotes, academically mined from the history of modern art. Moving at a staccato pace, the European expressionist movement must be caught on the run.

Developing at an incredibly fast pace, the output of the Three Cs—the Italians Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, and Enzo Cucchi has electrified the art market. Largely through the 1980 writings of Italian critic Achille

Bonito Oliva, the Three Cs share a theoretical framework and the racy sobriquet, the Italian Trans-Avantgarde.

The trans-avant garde premise—the nomadic nibbling of every experimental painting under the sun—blasted off with such torque that Oliva returned to the typewriter and composed another movement, the International Trans Avant garde, admitting the Germans Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, and Rainer Fetting, along with American troops, Julian Schnabel and Jon Borofsky.

Tension-filled angst characterizes the German wing of the new expressionism—as if these artists are jousting with the ghosts of Nazi Germany and the earth-scorching assault of the Third Reich. Their gut-wrenching aesthetics create an edge to the dreamier mythology pouring forth from the Italians, who seem most at home with the bacchanal exuberance of a Caravaggio. That remains the key difference between the Germans and the Italians. Another sharp contrast concerns geography. Sandro Chia and Francesco Clemente have studios in New York, more or less living and working as expatriates. Their art generates considerable fireworks in New York, but barely a whisper south of Milan.

The Germans, though, are solidly entrenched in their native land, resurrecting a love affair with the Teutonic landscape, where one can almost hear Wagnerian strains in the distance. In the same light, technology and contemporary architecture are absent on the Italian front but are almost a signature with the new German work—whether it’s the bizarre night life of Helmut Middendorf’s paintings or the massive facade of a government building in K. H. Hodicke’s canvases. The ideologies expressed in color and light accentuate these differences and tailor their respective personalities. Chia characters are drunk with life and those in Fetting’s paintings flaunt a hard-core nihilism, filled with violence.

Despite the differences in ideology, both groups are intoxicated with the figure, the expressive brushstroke, and a fast-paced, prolific output. Harnessed to widespread and unrelenting coverage in art magazines and traveling museum exhibitions (from Villa Vizcaya in Miami to the Saint Louis Art Museum and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), the new art has achieved an overnight pedigree.

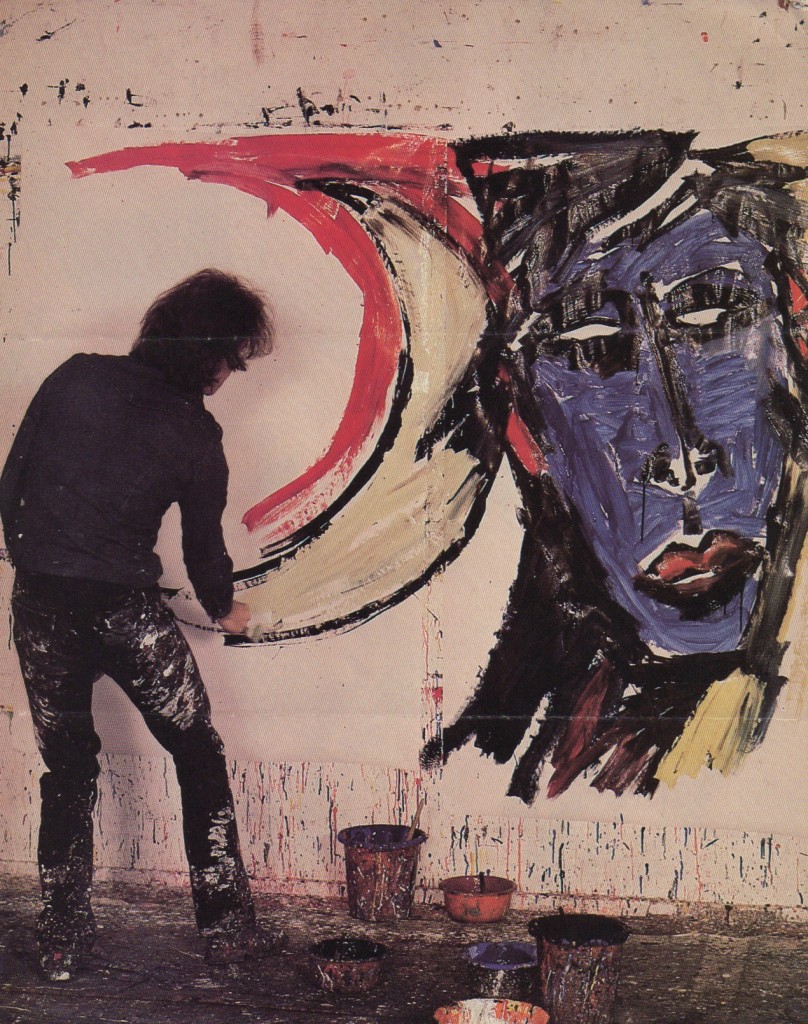

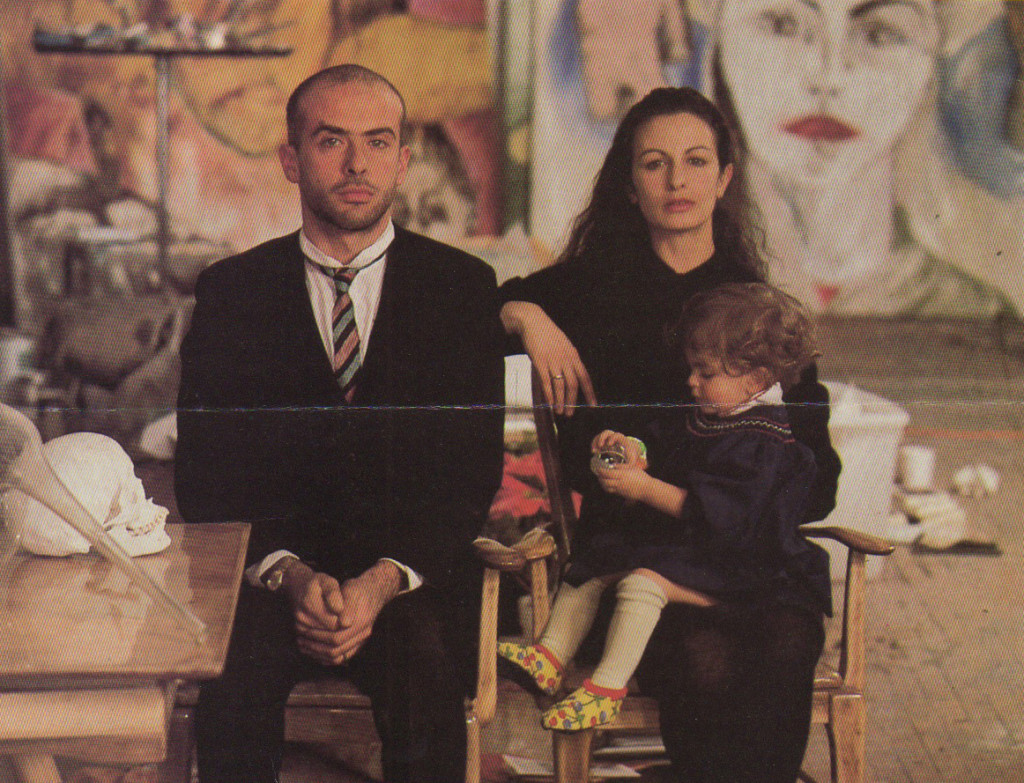

Bernd Koberling

Bernd Koberling, forty-five (above and opposite page), has enjoyed an eccentric career, supporting himself as a chef until 1968. The artist’s outdoor regimen includes forays to rugged Lapland and solo fishing, hiking, and painting. The influence of these “fresh air” activities is abundant throughout his works, providing a climate-controlled escape from the sordid Fauvism that haunts the work of fellow artists Rainer Fetting and Helmut Middendorf.

Koberling’s paintings are ambitiously huge, with his signature mix of oil and acrylic underlaying and overlaying the canvas. Intensely abstract in his imagery, he roams a landscape world of shifting, dripping cloud formations and condor-size birds meditating on jutting rocks. These highly charged, abstract landscapes are easy to digest.

Koberling is a veteran of Berlin’s Grossgorschen Thirty-five, the co-op gallery that launched the new wave of angst-imbued art. He has exhibited at the best German galleries since the late 1960s, from Galerie Rene Block in Berlin to Galerie Michael Werner in Cologne. In America he has shown with the Annina Nosei Gallery, one of the more avantgarde parlors of the new art.

Helmut Middendorf, photo by Ken Probst

Helmut Middendorf

The paintings of Helmut Middendorf (left) resemble crude tribal rites set in an underground context of punk-rock clubs and dimly lit streets littered with danger. Middendorf celebrates the nihilism of Berlin, splashed with chili-hot colors. With his compatriots—Rainer Fetting, Salome, and Bernd Zimmer—Middendorf formed

the cooperative Galerie am Moritzplatz in 1977, which has evolved as a center for heftig (violent) painting. Set in the working-class slum of Kreuzberg in West Berlin, surrounded by a bizarre nightlife, these fragmented works project a debauched environment. Middendorf was showcased at the Goethe Institute in London exhibition “Ten Young Painters from Berlin,” that was followed by a two-man show with Rainer Fetting at the Mary Boone Gallery. A veteran of the “Zeitgeist” show in Berlin, Middendorf has soloed at the Galerie Yvon Lambert in Paris and participated in last month’s group show, “European Expressionism” at the Annina Nosei Gallery in New York.

Georg Baselitz, photo by Ken Probst

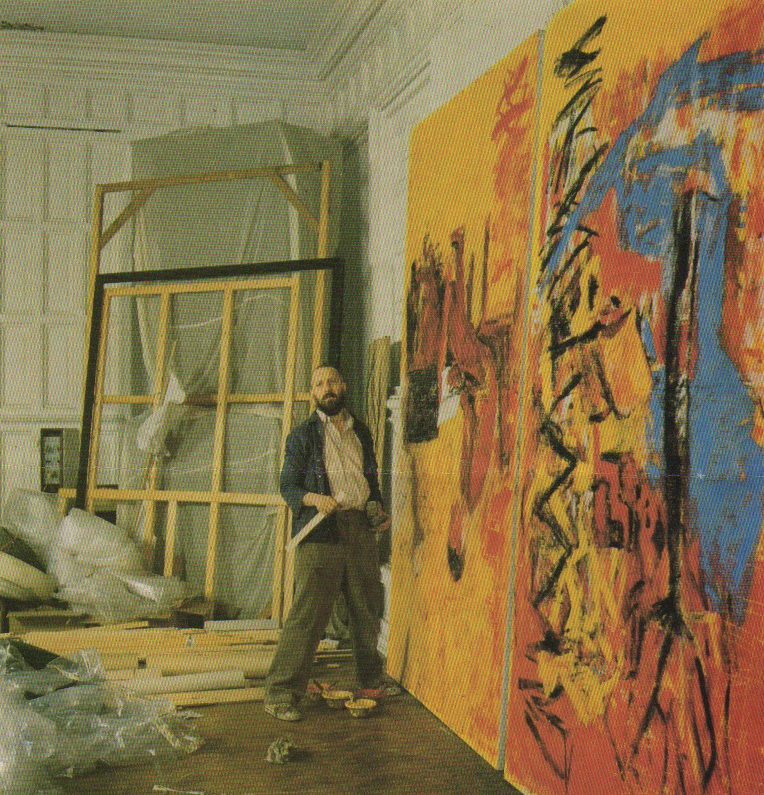

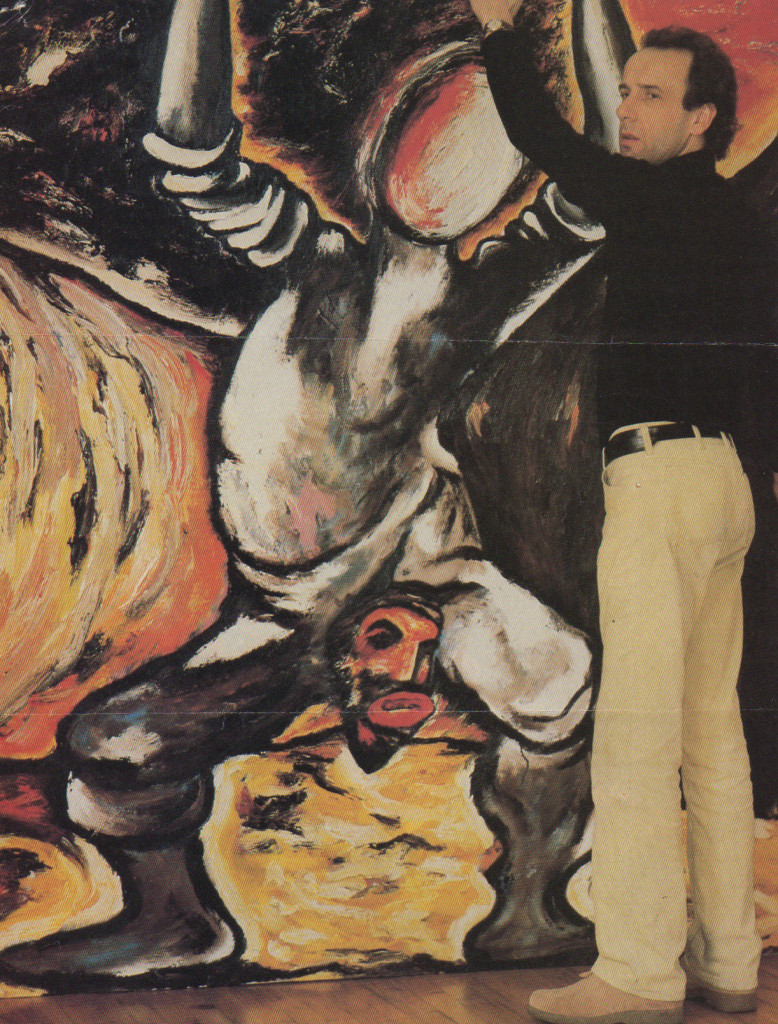

Georg Baselitz

Georg Baselitz’s technique of painting figures as if they were standing on their heads is an ongoing metaphor for his view of the contemporary state of world affairs: the ugly partition of his German homeland, the deep scars of World War II, and the panorama of holocaust in the modern world.

It is nearly impossible to keep abreast of Baselitz’s exhibitions. In 1982 he had seven solo shows, from the Sonnabend Gallery in New York to Galerie Michael Werner in Cologne, to Young Hoffmann Gallery in Chicago. This year poses similar logistical fireworks for the forty-five-year-old German artist, since at least four major galleries claim to be the main purveyors of his work. Baselitz seems headed for a radical shift: a spring show at Mary Boone Gallery. Boone has recently merged forces with Michael Werner, and it appears that Sonnabend and Fourcade galleries will be minus a superstar in their respective showrooms.

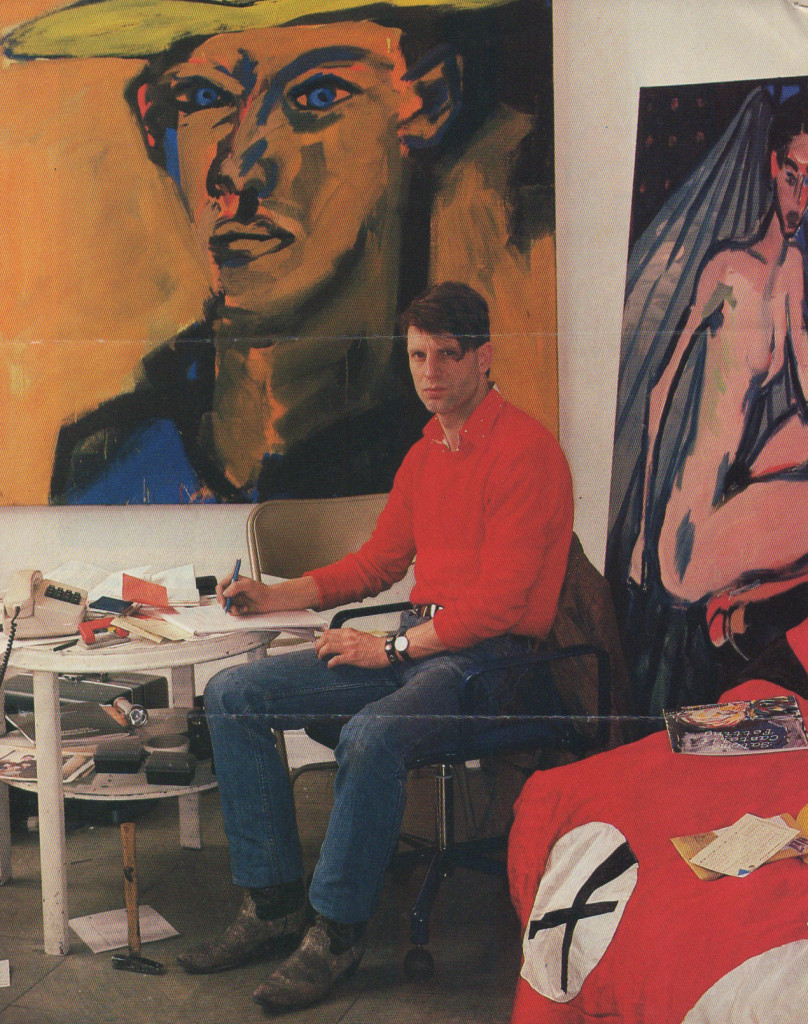

Rainer Fetting, photo by Ken Probst

Georg Baselitz

Rainer Fetting’s garishly lit, crimson splashed canvases project an unsettled urgency. A bent-over figure cloaked in purple haze scurries under an elevated train whose powerful headlamps beam an eerie, yellowish light across the horizon. A bevy of male nudes shave in front of fluorescent-lit mirrors or shower under torrents of blue water.

The shock value of Fetting’s work is rooted in the clandestine culture of New York gay bars and the hypnotic decibels of West Berlin punk-rock bands. A raving colorist with sweeping brushstrokes (a hallmark of the Berlin scene), Fetting, at thirty-four, snares the trophy for outrageousness.

The notion of celebrating male nudes on canvas has been mostly off-limits in postwar Germany—Fetting’s enthusiasm for such taboo topics has not diminished the international clamor for his work. He has had solo exhibitions at the Anthony d’Offay Gallery in London, Galerie Bischofberger in Zurich, Mary Boone in New York, and the acclaimed “Pressure to Paint,” group show at the Marlborough Gallery, New York, in 1982.

Recently in New York, Fetting showed new paintings at Annina Nosei’s “European Expressionism” show. From Basel to Bordeaux, Fetting has challenged aficionados to view his exotic world.

K. H. Hödicke, photo by Ken Probst

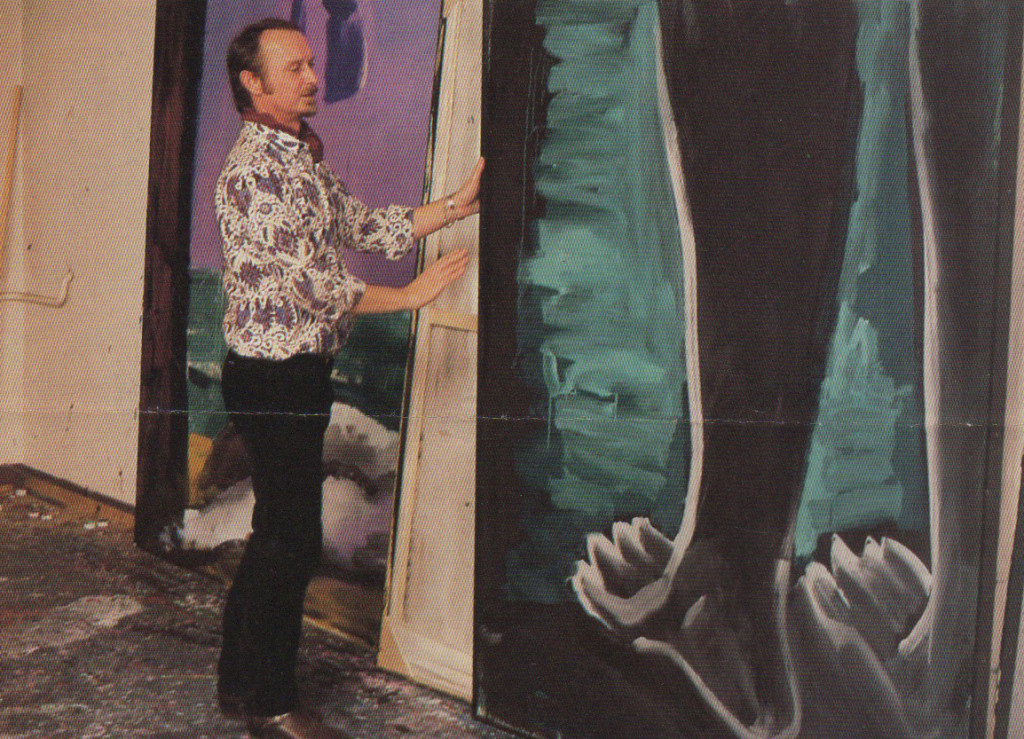

K. H. Hödicke

After Joseph Beuys, the first postwar German artist to capture the imagination of the West, K. H. Hödicke is the first artist to wield profound influence on the young painters of West Berlin. From his back-lit figures and garishly artificial light to muslin thin canvases and rationed dollops of powdered acrylic, Hödicke, at forty-five, holdsa Pied Piper grip on the young. The mobility of his paintings make sense in the frenzied world of prolific output and global travels.

Hödicke’s inclusion in the important exhibition “A New Spirit in Painting” at the Royal Academy in London (1981) and well-received solo shows at the Annina Nosei Gallery in New York (1982 and 1983) and the L. A. Louver Gallery in Los Angeles (1982) augur another painting star.

Hödicke’s German dealer, Folker Skulima, devoted expensive wall space to the artist last May at Chicago’s renowned art exposition at Navy Pier. From Hödicke’s first New York appearance in the 1976 “Made in Berlin” exhibition at the Galerie Rene Block to the 1983 Tel Aviv Museum show, “New Paintings from Germany,” his slashing strokes and brute imagery guarantee first-class inclusion in the new wave of European expressionism.

Sandro Chia

Sandro Chia comes closest to attaining cult status among the Three Cs and has set up shop in New York with loft space in the same building as Julian Schnabel. Like his fellow European expressionists, Chia boasts a prodigious number of canvases and sculptures—a crucial factor when mounting concurrent shows in Europe and the United States. Chia’s images are exuberantly fat and sassy, dancing on a tightrope held by Picasso and Giorgio de Chirico. Chia delights in quoting from both obscure and famous practitioners of modern art. Chia jumps back and forth between painting and sculpture with elan and the kind of corporate resources required to cast giant bronzes at the best art foundries.

Chia (at the age of thirty-seven) has run into some nettlesome criticism jabbing at his slipshod production and puffed-up chutzpah. In his New York show last spring at Leo Castelli, Chia was blasted by Robert Hughes in Time for his “stodgy and overblown” parodies, “floating on gaseous clouds of hype.” The barbs of any adept critic have yet to puncture Chia’s operatic bubble.

Francesco Clemente, photo by Ken Probst

Francesco Clemente

Aside from his exclusion (some critics would say outright snubbing) from the 1982 Guggenheim exhibition “Italian Art Now: An American Perspective,” Francesco Clemente (above) has an unblemished track record almost identical to that of Sandro Chia (also like Chia, he lives in New York). Clemente, at thirty-one, projects a street-urchin toughness to images that neither mars their dreamy, fresco-like surfaces nor diminishes their breathless quality. The most poetic of the Three Cs, Clemente’s paintings quiver with the moodiness and sexual flare of a Caravaggio.

Since his 1977 exhibition at Galleria Gian Enzo Sperone in Rome, Clemente’s images have crisscrossed Europe. They have been exhibited by Bruno Bischofberger in Zurich, Anthony d’Offay and the Whitechapel Gallery in London, Daniel Templon in Paris, James Corcoran Gallery in Los Angeles, and Sperone Westwater Fischer and Mary Boone galleries in New York. Clemente was one of forty-six ember-hot young painters showing in the giant

“Zeitgeist” exhibit in West Berlin last winter.

Enzo Cucchi, photo by Ken Probst

Enzo Cucchi

Enzo Cucchi shuns the limelight of New York and Rome in favor of his native Ancona on the Italian Adriatic coast. The primitive power that rips through his canvases makes him the wild child of the Three Cs, an artist whose brush seems ablaze. Compared to the narratively slick surface of Chia or the gentleman-poet style of Clemente, Cucchi gravitates to the “scorched canvas” policy of German painter Anselm Kiefer. The country ways of Cucchi float like music across his mottled landscapes.

In a recent interview in an Italian art magazine, Cucchi blustered, “The art world is in a state of bedazzlement, and it’s being dazzled by Italian art. If it weren’t for Italian art, there would be nothing.” Cucchi’s bravado in words and images cannot be dismissed outright. Gian Enzo Sperone, the dealer who directs the Three Cs’ itinerary, wants Cucchi to show at Leo Castelli, a favorite tactic for superstar artists: “double-wall” it and your stock soars. Cucchi hates the idea (in print anyway) of the prospect of two lordly dealers fighting tooth and nail over the hermetic artist’s New York-bound work—the stuff of which legends are born.

Cucchi’s headless horses and crowing black roosters have roared through the exhibition circuit of Rome, Zurich, London, New York, and Paris. He has even managed to startle natives of more tropical climes, including the

1979 Sao Paulo Biennale in Brazil.