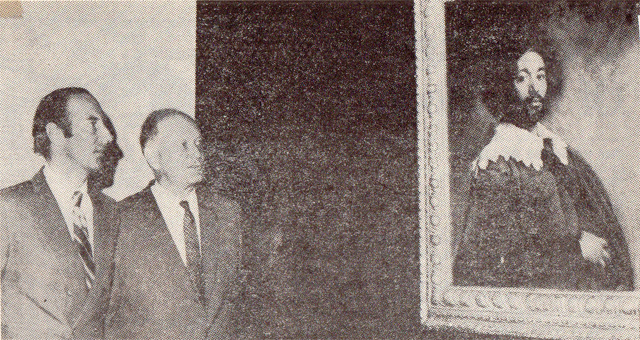

Thomas Hoving (left) with C. Douglas Dillion gazing at the Met’s new acquisition, Velazquez’s “Juan de Pareja”

Thomas Hovings’s tell-all account of his decade at the helm of the Metropolitan Museum of Art is as action-packed as his definition of what a museum director needs to be: “part gunslinger, ward heeler, legal fixer, accomplice smuggler, anarchist, and toady.”

Hoving ruled from 1967 to 1977, a glory time when the Met doubled its exhibition acreage in Central Park, adding wings, glass-covered pavilions and multi-million dollar acquisitions. With silky banners outside trumpeting blockbuster shows and fresh flowers inside the great hall to greet the masses, the Met eventually outdrew the Statue of Liberty as the city’s number one tourist attraction.

According to Hoving – and there is no other filter here – the Met’s great leap from a dusty repository into world-class museumhood was all his doing, a breathless juggling act, cajoling stubborn trustees, thin-skinned patrons, testy curators and greedy smugglers to do the right thing. His gun-toting approach as “dictator of taste” created a revolving door of disgruntled staff members, such as the veteran design director who shouts at Hoving before quitting, “Don’t expect me to get involved in this vulgar circus.”

For “In the Presence of Kings,” his first exhibition effort as director in 1967, Hoving installed a small gift shop selling facsimiles of ancient gold coins near the entrance of the show, an historic event for the Met in Hoving’s opinion and definitely standard equipment in museum-land today. “Kings” drew 247,000 visitors in its eight-week run, a portent of the director’s devotion to the box office and his master plan to make the Met “the biggest, richest – and loudest – museum in the cosmos.”

A huge cast of characters races in and out of his chronological and, at times, numbing tale, a seemingly endless quest for rich patrons, precious objects and publicity. Evocative though often nasty thumbnail sketches accompany a breezy writing style that bristles with direct quotes. The authoritative parade of verbatim conversations was assembled by the author in daily dictating sessions during his tenure, making it a kind of pre-packaged memoir.

The jabbing combinations help to lighten the heavy load of boardroom intrigues and tiresome boasting by the youthful director who abandoned his politically appointed post as New York City’s Parks Commissioner under Mayor John V. Lindsay to run the museum. Hoving had previously served the Met at the Cloisters as a curator in medieval art. Apprised of his decision to leave Parks, Lindsay told Hoving, “Seems to me the place is dead. But . . . you’ll make the mummies dance.” It was a grand prediction.

Among the array of mini-sketches, a dour-faced trustee (Roland Redmond) has “rheumy eyes, which looked like day-old oysters” and an emerald-encumbered heiress in dark glasses (Florence Gould) resembles a “mafia mistress.” J. Carter Brown, first introduced as a contender for the Met’s directorship, is described as “the socialite assistant director of Washington’s National Gallery married to the adopted daughter of the gallery’s major patron, Paul Mellon.” Brown later becomes Hoving’s arch-rival and frequent victor in their cutthroat competition for masterpieces and blockbuster loan shows.

The name-dropping is reliably entertaining. On a luxury antiquities cruise to Corfu as guests of the oil-rich Met trustee Charles Wrightsman and his wife, Jayne, Hoving recounts the couple’s excited announcement that the young King Constantine of Greece, his wife, sisters and Queen Mother Frederica would be joining the party for lunch. “Cecil Beaton blurted out, `How amusing! Mum the Hun {the Queen Mother} for lunch – oh how chic, Jayne!’ ”

From the wings of Hoving’s world stage-set, you learn that Andre Malraux looked “addled,” Nelson Rockefeller was a tightwad trustee (though he gave his exquisite primitive art collection to the Met) and that Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis threw a fit over the phone when Hoving asked her to support the Met’s orchestrated bid to win the Temple of Dendur over a competing site in Washington.

But despite the spectacular display of details, few revelations are aired about how a world-class museum such as the Met functions other than by Hoving’s one-man Machiavellian exploits. When he tells Douglas Dillon, his boss on the board of trustees, that plans for the four new wings and restoration of existing galleries will cost between $65 and $85 million, Dillon responds, “Oh, let’s go ahead. The next generation can pay for it.”

While many of these episodes sparkle with believeable behind-the- scenes drama, such as the Met’s successful $5.5-million bid for the Velasquez masterpiece “Juan de Pareja,” other accounts fall flat.

Controversial deaccessioning (“the standard museum word for getting rid of things”) and the acquisition of treaty-protected antiquities executed by Hoving and his staff caused a great ruckus in the 1970s. The deaccessioning brought censure from a number of art associations and even an investigation by the New York attorney general.

Hoving replays much of this media-fed controversy to the extreme, meticulously noting the newspaper and magazine accounts and even personal backgrounds on some of the writers. Curiously, Hoving leaves out The Grand Acquisitors, John L. Hess’s 1974 book-length investigative account of the Hoving years at the Met. Hess, a former New York Times reporter, called the period a “Watergate in Art.”

Side by side, the two books provide a more satisfying and broad- stroked picture of that epoch-making time. Reading Hoving alone is like taking the “Hoving treatment,” defined by a Soviet Ministry of Culture official as “you know – poetry and bull.”