Frank Stella, “Whale Watch”

Frank Stella is the only living American artist to have been honored with two retrospectives at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. At his Hong Kong debut, in association with Mandarin Fine Arts, he unveiled his latest, and possibly greatest, work. Judd Tully interviewed him.

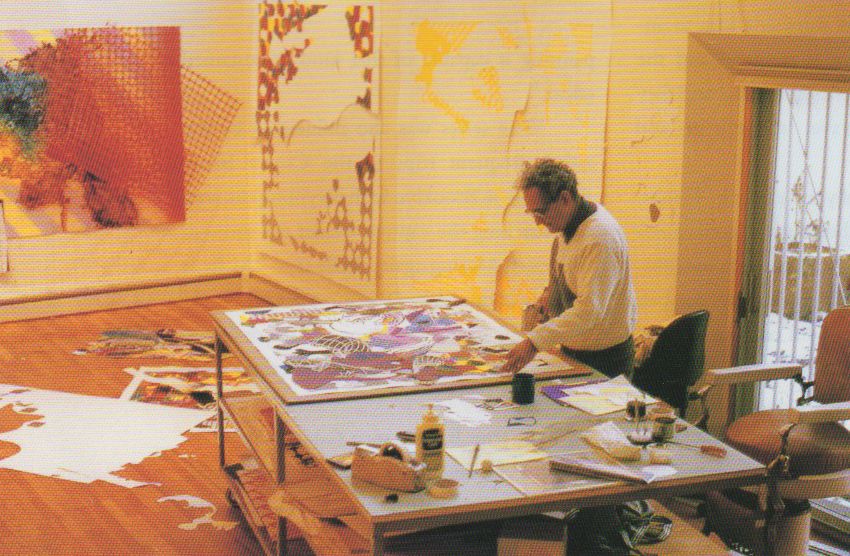

You have to watch your step while navigating the incredible clutter in artist Frank Stella’s massive Manhattan warehouse studio, big enough to house a duplex stableful of horses and then some. In fact, during the 19th century, the building served as an auction house for horses and, later, horseless carriages. You learn about the building’s history almost immediately, because the 57-year-old Stella, one of the world’s most famous contemporary artists, is obsessed with the past and its relationship to the present.

Somehow, the cacophony of studio sounds and the apparently haphazard melange of work tables, saw horses, tools, blueprints, drawings, stencils and other less identifiable objects that cover every surface help to explain the artist’s world — a place where collage rules.

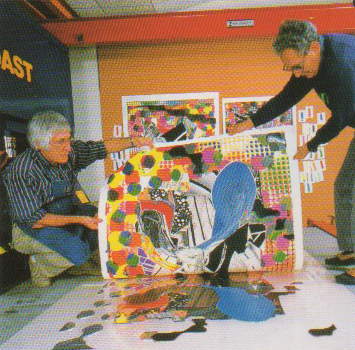

Stella with Ken Tyler

Stella jokingly refers to the floor-to-ceiling chaos as his “debris d’atelier”. Only he, along with a small crew of young and precocious assistants, can make sense out of it. The scene looks like a gigantic movie-set for a lost and found emporium. He directs the action with invisible signals, creating a kind of workshop choreography that appears slapdash yet is extremely disciplined. It is hard to keep up with the fast-moving and fast talking Stella as he nimbly negotiates a narrow throughway between some makeshift tables and a row of wall-mounted sculpture reliefs the size of basket balls, their respective edges sharp enough to deliver a close shave.

Pointing to one nine-foot-high relief painting that juts out from the wall in a blaze of exotically mixed colours, I asked if it was “spoken for”. Chuckling at the question, he confessed: “Not any more, not with the current dip in the market. It’s probably heading into storage.” In seconds, he adjusts his response with a more upbeat spin: “But you know, all in all, these works find homes one way or another.”

During the great art boom of the late 1980s, Stella, primarily through his New York dealer Knoedler and Company, sold many of these abstract behemoths to museums, corporations, foundations and private collectors, especially in Germany and Japan. In the same period, one of his early, minimalist-style, black-enamel striped paintings from 1959, titled Tomlinson Court Park, sold at Sotheby’s in New York for a record US$5 million.

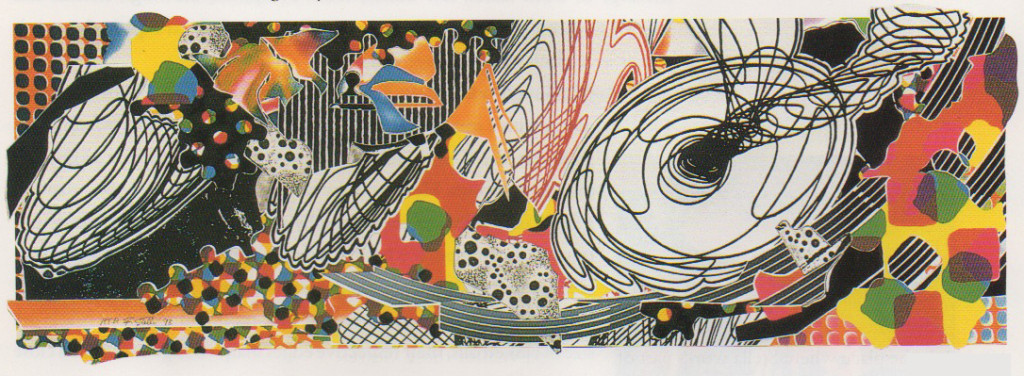

Frank Stella, “Monkey Rope”

The background behind that painting is fascinating. Stella was all of 23 and fresh out of Princeton University when he arrived with it and stepped into the art world with his “black” paintings. It was a time when the emotionally charged reign of Abstract Expressionism dominated the scene. One established newspaper critic branded Stella’s huge and unsettling paintings that were exhibited in a group show at the Museum of Modern Art as “unspeakably boring” and confidently described the artist’s process as “carefully lined with white pinstripes”.

Stella wrote a letter to the editor correcting the famous critic. “In fact, I paint black

stripes about two-and-a-half inches wide. Therefore the unpainted white spaces between them are not the stripes but what you call the background’.” The paper printed the correction and prominently reproduced Tomlinson. Court Park. In 1984, the artist made headlines when he was arrested for speeding in his silver Ferrari on a New York state highway, clocked at 105mph. Stella’s community-service sentence was his own idea, giving the local upstate town free lectures on art, similar in scope to the talks he was commissioned to deliver at Harvard earlier that year.

Frank Stella working on his “Moby Dick Deckle Edges” project in his Manhattan Studio

More important than the headlines, though, is the fact that Stella is the only living American artist to have been honored with two retrospectives, in 1970 and 1987, at the Museum of Modern Art. Pablo Picasso was the only other artist to duplicate that feat.

Stella stalks the latest advances in cutting-edge technology, from powerful computer software for cooking up three-dimensional images, to space-age metals fabricated for his corporate-sized sculptures. He also studies and learns from the past, especially the rich history of painters and paintings.

With all this fresh in mind, the studio visit was arranged as a sneak preview of the artist’s Hong Kong debut at the Art Asia ’93 Fair, in association with Mandarin Fine Arts, where some of his work will be featured in a special American artists show in January, when Stella will again be a guest of Mandarin Oriental. Hong Kong will be privileged to see the premier showing of his latest and most ambitious (to date) handmade paper-print project, titled Moby Dick Deckle Edges.

The visit had been inadvertently delayed because the fax requesting the interview wound up on the studio floor with the rest of the flotsam and jetsam. “I only stepped on it this morning,” joked Stella, fingering an unlit cigar.

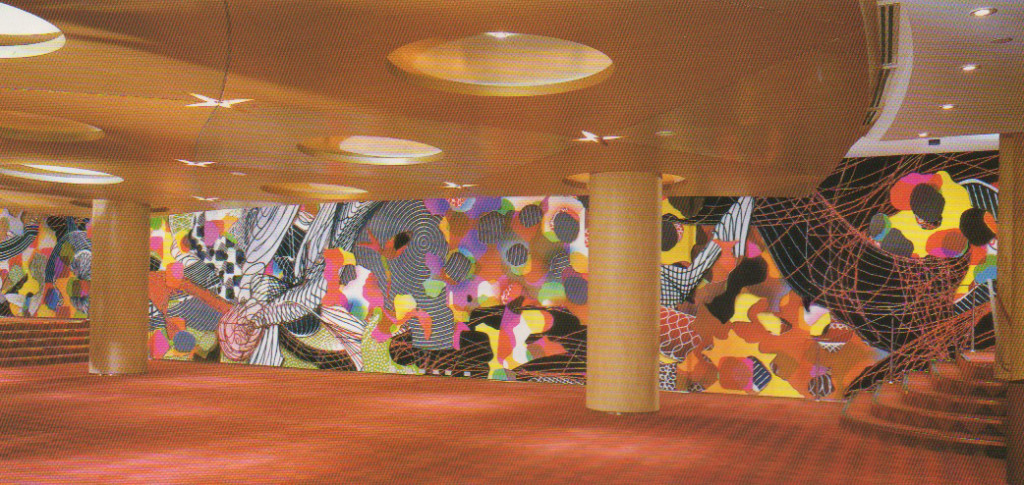

Stella’s coloulul murals in the newly built Princess of Wales Theatre, Toronto

None of the Hong Kong-bound work was in the studio, though. All nine editions of the combination lithograph, etching, aquatint, relief, screenprints were an hour’s ride away at Tyler Graphics in bucolic Mount Kisco, New York. It is the place where Stella works part of his multimedia magic, in collaboration with master printmaker and entrepreneur Ken Tyler.

Stella and Tyler have worked together since 1967, producing more than 100 limited editions. Tyler acts as a kind of hi-tech engineer, the Scotty of Stella’s Starship Enterprise. “This place is an extension of Frank’s studio,” says Tyler. “He never stops working.” The artist’s current print project keeps a 12-person crew there hopping full-time. “When it’s all ready to go,” enthuses Stella, “you put the ink on the thing and then bang, you know it’s a one-shot deal. You just wham it in.”

his reliefs on rows of theatre seating

Moby Dick, of course, refers to the Elr eat 19th-century American novel by Herman Melville about Ahab hunting the great white whale. Stella has devoted the better part of a decade to making collages, sculpture, prints and mural-sized relief paintings from the book’s 135 chapters. There’s a Stella image for every chapter. The decide edges in the title refer tothe irregularly shaped painted margins of the handmade paper, a dramatic device that intensifies the floating-island quality of the images.

Even for those viewers already familiar with Stella’s intensely abstract and techni-colored geometries, the idea of a storyline or narrative behind his visually woven art is a bit unfathomable. Asked about the relationship between Melville’s novel and Stella’s art (his titles for individual works, such as Monstrous Pictures Of Whales, come directly from the book), Stella says: “It is not directly based on the novel, chapter by chapter, but it’s a kind of association. I don’t mean to impinge on Melville in any way. I just follow the example.”

He expands on the association between his current work and Melville’s: “A lot of the continuity in Melville is not so different from collage. Melville jumps from one idea to another, and the rhythm is so great and the imagery is so good, he puts it together and they work. It’s like the wave, it’s very up and down.”

Outfitted casually in a black T-shirt, nondescript chinos and boating moccasins, Stella continued his multilayered answer in mellifluous yet staccato bunts, just a few decibels louder than the incessant din coming from all corners of the studio. “It has a sustained kind of imagery that is basically the wave and the whale forms. You can’t really tell a story because it is abstract, but you get the sense of the forms and the shapes relating to each other. I’m just trying to make a similar kind of voyage to see if painting is capable of that kind of sustained effort.”

The series was also influenced by the artist’s frequent trips to the Coney Island Aquarium in Brooklyn with his young children and watching the captive whales cut through the water. Musing again, Stella says: “As far as its being about Moby Dick, most people would say, ‘I don’t get it.’ But if you saw ten or fifteen of the pieces, you might begin to get some sense of it.”

In true Renaissance fashion, Stella whom Tyler describes as more of a maximalist these days, rather than the minimalist that he made his name as is not content with expressing himself in a single medium and is one of the few artists working today who have seriously and successfully tackled other disciplines, including architecture. One recent collaborative project at the new 2,000-seat Princess of Wales Theatre in Toronto involved huge murals and acoustics-enhancing relief sculptures for the theatre’s boxes and balconies.

Still on his architectural discourse, Stella moves to another table-top and taps on the roof of an unpolished, stainless-steel model he designed for a new museum in Holland. “You could build this sixty-six feet high for only US$15 million. We’re trying to make a geometry that fits into the urban setting, that’s rigid but not absolutely beholden to the rectangular and right-angled architecture that we have.”

Asked about the status of the project, Stella deadpanned: “They got mad at us because we kept improving our idea and changing it.” He is famous for his Promethean production, his uncanny ability, year after year, to come up with freshly inventive imagery, executed in a bewildering array of media and scale. But the Moby Dick project is, as Stella puts it, “worthy of Ripley’s Believe It Or Not“.

Pressed as to whether he envisioned seeing the whole series in a museum setting, Stella chuckled again and said: “I don’t know anyone who could afford it. Besides, I’m not sure that I’d want to see all of it — what if I didn’t like it?”