For this writer, the works of Donald Judd, especially the iconic, color charged metal and plexiglas untitled sculptures known as ‘stacks,’ have always had a regal, art market tint to them, as they would episodically appear at an auction house preview of blue chip contemporary art.

I can easily picture, for example, the particular wall at one of the major houses in New York where the ten-unit stacks always go, elegantly cantilevered off the wall and despite the commercial context, the light infused units, shiny or matte and replete with dynamic harmonies of positive and negative spaces, consistently stopped this viewer in his tracks.

I’m not at all sure why. Perhaps it’s because the stack is never static, relentlessly opening new vistas of observation and exploration for the viewer or that the inherent transparency of the plexiglas allows for immediate entry into the cathedral like interior of the multi-tiered structure.

Other personal encounters with Judd’s stacks seem even rarer, as in 2005 in Dallas during an eye-opening visit to the Richard Meier Rachofsky House, where a ten-unit stack, “Untitled #91-3” from 1991, fabricated in anodized aluminum and hotly colored in Cadmium Red Light with smoky grey plexiglas, easily stood up to the sleek architecture, or in 2006 when an early stack, “Untitled,” from 1967, executed in a pine forest shade of green lacquer on galvanized iron, was on temporary view in New York at the Museum of Modern Art as a beacon for what the museum strives for.

Installation view of the exhibition Painting and Sculpture:Inaugural Installation, at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 20, 2004-tbd

It is seemingly unprecedented then, to have the opportunity to see and selectively commune with nine examples of Judd’s hi-rise pieces (plus one single stack) in one environment, as if part of Marfa, the artist’s Giverny in Texas or Judd’s cast-iron SoHo loft building/museum at 101 Spring Street, temporarily came north to camp out in the environs of the Upper East Side.

The number of stacks here, in fact, greatly exceed those assembled for any previous gallery or museum exhibition, including the landmark Donald Judd survey at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa in 1975 or the more recent Tate Modern retrospective in 2004.

In the current iteration, there are two stacks from 1968, single examples from 1970, 1978, 1980 and 1988 and two stacks from 1989 and 1990.

The materials in the floor-to-ceiling height examples run the Judd gamut, from galvanized iron, stainless steel and anodized aluminum, while the eight fitted with plexiglas, either the so-called wrap-around pieces or those slotted with top and bottom plexiglas panels, include a color palette of amber, light green, red, yellow as well as clear.

As with all stacks in the Judd pantheon, there are two uniform sizes.

Of the ones on view, seven are scaled at 6 x 27 x 24 inches for each identical unit while three are scaled at the larger 9 x 40 x 31 inches.

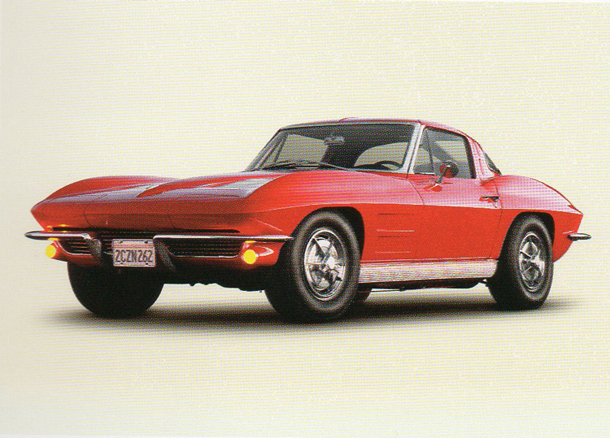

Corvette Stingray split-window coupe from 1963

In like fashion, or more precisely, according to the artist’s strict specifications, the six-inch high units are separated by six inches of negative space, starting from the floor level and nine inches for the larger scale.

To get a sense of this totemic scale, one would need a ceiling height of sixteen feet to faithfully accommodate the larger version of the ten-unit stack as Judd envisioned it.

For this viewer, the stacks bring to mind other singular objects, say the rakish silhouette of a 1963 fiberglass bodied Corvette Stingray, painted in a blazing shade of Roman Red, or the constructional clarity of Mies van der Rohe’s (and Philip Johnson’s) bronze and bronze-glass Seagram tower on Park Avenue.

You might not recall the model year of the car or the name of the architect, but like the Judd stack, there’s an instantaneous visual connection with the object, one that is both unique and memorable.

There are many ways to approach Judd’s uncanny range of three-dimensional works and one direct path would be tracking the artist’s own voluminous writings about his art and others, or sampling as a kind of print DJ the long roster of distinguished art critics and academic heavyweights that have opined about and analyzed his art for close to five decades, and still going strong years after the artist’s early passing at the age of 65 in 1994.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, The Seagram Building, 1958, New York, NY

Apart from these chance encounters for direct observation, the approach I’ve taken in appreciating the work leans more towards some of the things Judd expressed to various interviewers over the years. Those at times terse morsels seemed to yield more clarity or clues about his vision than the rather staggering archive of art criticism that compulsively traced his every step.

Having barely survived high school geometry, the notion you would need to understand the formula of the Fibonacci sequence in order to comprehend the spatial logic anchoring Judd’s work, was somewhat intimidating until I read that Judd didn’t give a toss if the viewer understood or even recognized his obsession with measurements and number systems as long as one fathomed an underlying order within.

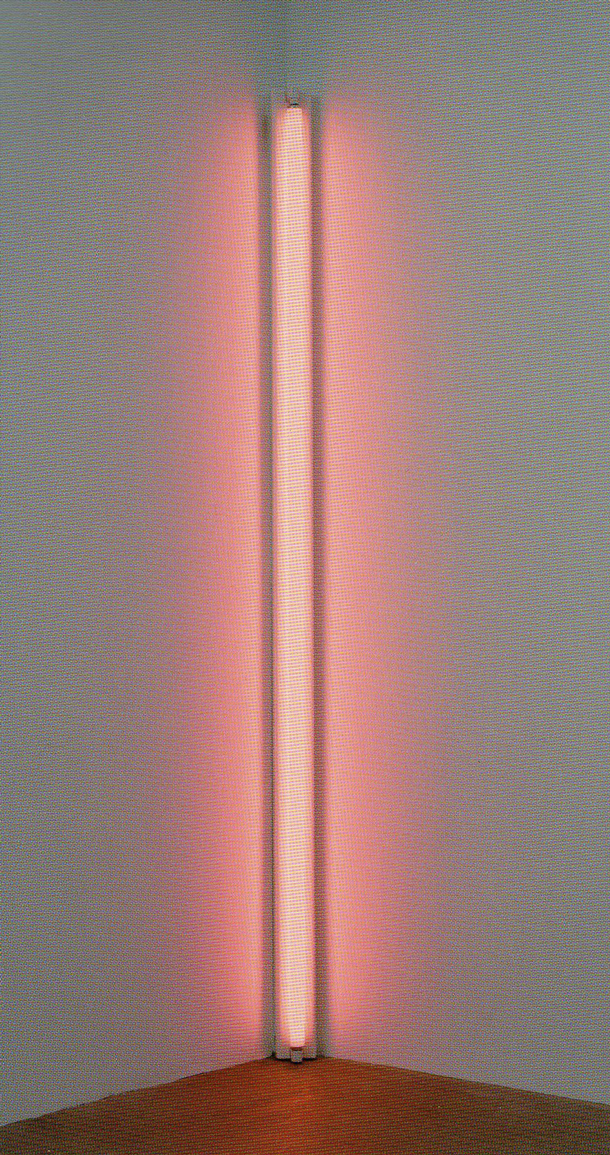

In approaching a way to write about Judd’s stacks, it felt a bit like a line in his stellar review of Dan Flavin’s sculpture in 1964: “I can’t think of a way to describe it.”

In a February 1965 oral history interview for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, for example, Bruce Hooten, the art reviewer and future publisher of the bi-weekly tabloid Art/World, tentatively asked the 36 year old Donald Judd about his approach to art making.

Dan Flavin, Pink Out of a Corner-To Jasper Johns, 1963, Flourescent light and metal fixture, 96 x 72 x 5 inches (243 x 182 x 13 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Philip Johnson

Explaining that he received a degree in philosophy from Columbia and studied at the Art Students League (as Jackson Pollock and David Smith had decades earlier), Judd said he was a painter until ’61-62 and then started “doing three-dimensional things.”

Judd elaborated, “Well I’m not interested in the kind of expression you have when you paint a painting with brushstrokes. It’s all right, but its already done and I want to do something new. I didn’t want to get into something which is played out and narrow. I want to do as I like, invent my own interests.”

The timing of the formal interview was rather extraordinary, coming about a year after his first solo at Dick Bellamy’s Green Gallery and just after Judd’s inclusion in the cutting-edge group show, “Shape and Structure” at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York that had opened the month before.

That exhibition brought one of the artist’s first three-dimensional floor pieces, “Untitled” from 1964, in cadmium red light enamel on galvanized iron, into a broader public view.

“Shape and Structure,” a rather jumbled pastiche, at least according to accounts at the time, was co-curated by Henry Geldzahler and Frank Stella and brought, among others, Judd, Carl Andre and Robert Morris, a soon to be trinity of the Minimalist movement, together for the first time.

Judd’s piece, resembling to some the shape of a life raft or perhaps a swimming pool, was acquired in November 1971 by aspiring world-class collectors Helga and Walther Lauffs, and the rest as one might say, is history.

Hooten, seemingly more comfortable critiquing the likes of an Edward Hopper or Franz Kline painting, was clearly fascinated by Judd’s alarming new work and tentatively probed for more answers, perceptively asking if Judd enjoyed “building your pieces.”

“Building is just skilled labor, I suppose” the artist responded. “It’s a lot of work. I don’t mind other people building them, but the way things go together and are made is interesting to me. I like that a lot. I pay a lot of attention to how things are done and the whole activity of building something is interesting.”

A bit later in the interview, Judd returns to the subject of fabrication and said, “I’ve had a tinsmith make a few when I’ve gotten hold of some money. I am just as satisfied with their joints—maybe more so—as I am with mine. Also, I can’t make as many as I could conceivably buy.”

Asked what he thought of Judd’s work back then and whether it felt like the shock of the new, Frank Stella told this writer, “actually it was a lot simpler then. Nobody really thought about anything. There was no thought. Everybody was just doing it and taking it for granted. Sure, I liked it (Judd’s floor piece), it was 3-D and nice and seemed like what was going to happen or what was happening. There wasn’t much to talk about. You liked boxes or you didn’t.”

Of course, Judd was thinking hard about everything involving color, form, proportion and scale at that time, slowly developing a self-made vocabulary that assiduously avoided traditional compositional effects.

“I don’t want to be descriptive or naturalistic,” he told Hooten, “in any way.”

In that same contrarian vein, Judd consistently rejected the idea or label that he was a sculptor.

“No, it means carving to me,” responded Judd to a question by the German critic Katharina Winnekes, in one of his last published interviews in April 1993, less than a year before his died “…I never had a word; I don’t know.”

As Judd wrote in “Specific Objects,” “In three-dimensional work the whole thing is made according to complex purposes, and these are not scattered but asserted by one form.”…The thing as a whole, its quality as a whole, is what is interesting.”

Judd also talked about his decidedly American quest for creating a rigorous vocabulary in metals and plexiglas, one coupled with an acidic disdain for what was past, to art critic Bruce Glaser during a WBAI-FM radio broadcast in 1964 and later transcribed in Artnews in September 1966.

“I’m totally uninterested in European art,” said Judd, “I think it’s over with.”

Asked why he wanted to avoid compositional effects and instead, focus on what the artist described as “the one thing” or “ whole thing,” Judd answered, “well, these effects tend to carry with them all the structure, values, feelings of the whole European tradition. It suits me fine if that’s all down the drain.”

That same year, in February 1966, Judd would have his first one-man show at the Pop Art dominated stable of Leo Castelli and debut a wall-mounted, galvanized steel “Stack” piece in the dealer’s Upper East Side salon, a setting complete with ornate wall moldings and polished parquet floors.

Judging from a black-and-white installation shot of the exhibition/installation, the wall-mounted works, including the new stack, horizontal progressions and a free-standing floor piece, must have looked like metal clad invaders in a space decidedly more suitable for two-dimensional paintings and smaller-scaled works of art, say one of Roy Lichtenstein’s Brushstrokes or a cluster of Andy Warhol’s silkscreen ink on wood Brillo Boxes from the time.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain 1950 (replica of 1917 original), porcelain urinal, 12 x 15 x 19 (30 x 38 x 45 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift (by exchange) of Mrs. Herbert Cameron Morris, 1998

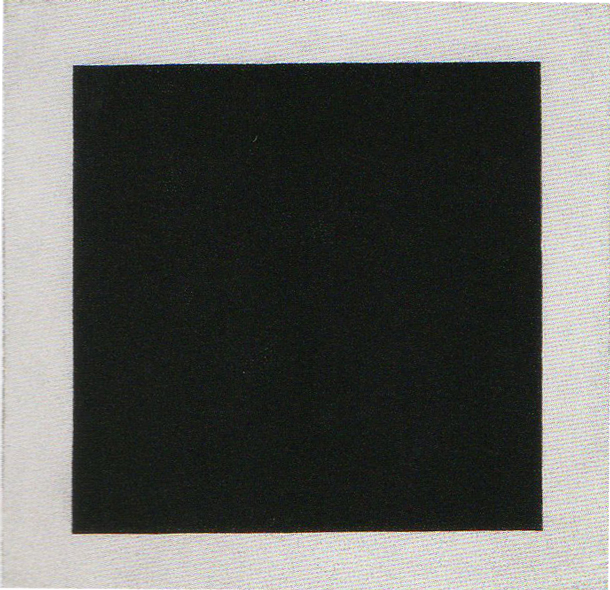

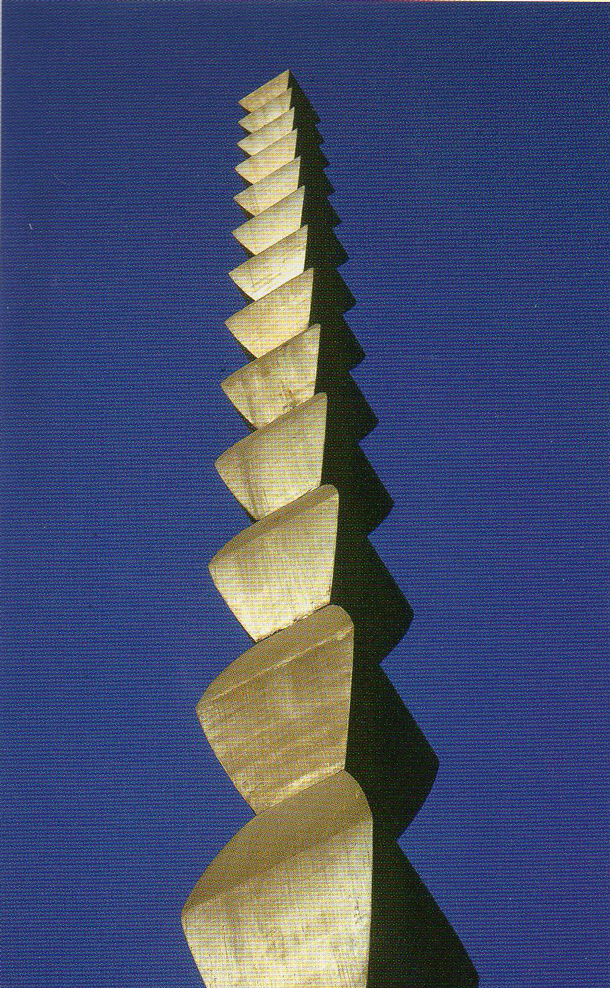

For the lucky viewer in those Castelli days, it might have carried the same jolt as seeing one of Duchamp’s original Ready-mades, perhaps the wood and galvanized iron snow shovel of “In Advance of the Broken Arm” from 1915 in Paris or in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) that same year, viewing Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist composition, “Black Square” or staring skyward at Constantin Brancusi’s 23 foot high, carved, rhomboid shaped “Endless Column” in the garden of Edward Steichen’s home in Voulangis in 1920.

Thinking about those early Judd pieces today, with their strict sequences of identical components, especially after hearing how he struggled to install the revolutionary seven unit stack on Castelli’s uneven wood lathe and plaster coated wall, even with the help of his burly close friend John Chamberlain and a young gallery assistant, underscores in part the heavy lifting, both physically and philosophically Judd was wrestling with.

The artist was simultaneously honing his hands-off approach to the industrial fabrication of the pieces, as mapped out in an untitled 1965 Judd drawing featuring the concise outlines of a six unit stack along with pencil notations indicating the 9 x 40 x 30 inch dimensions for each unit, the nine inch separation between each of the elements and short hand instructions for “22 G. Gal. Iron, Soldered Seams-No PITT. Seams, No Paint, 5 or More Boxes, Floor to Ceiling.”

Kazimir Malevich, Black Square, c. 1923, oil on canvas, 41 x 41 (106 x 106 cm), Russia State Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

“Judd had half invented, half discovered, a way,” wrote Peter Ballantine in the catalogue, “Working Papers-Donald Judd Drawings 1963-93” for the exhibition he curated at Spruth Magers London in 2012 “—the only possible way—to produce three-dimensional art works that were true objects, not imitation or artist’s objects.”

With his pre-determined geometry laid out on paper and sent direct to the factory floor, Judd had found his way to the simple, three-dimensional expression of complex thought.

“The boxes just hung on the wall,” recalled Judd in a 1971 interview with John Coplans, “in a practical manner.”

The vocabulary and fabrication model Judd developed during the ‘60’s became the conceptual platform for his evolving oeuvre in the subsequent decades.

Constantin Brancusi, The Endless Column, 1937, Cast iron and steel, 98 feet high, World War One Memorial Park, Tirgu Jiu, Romania

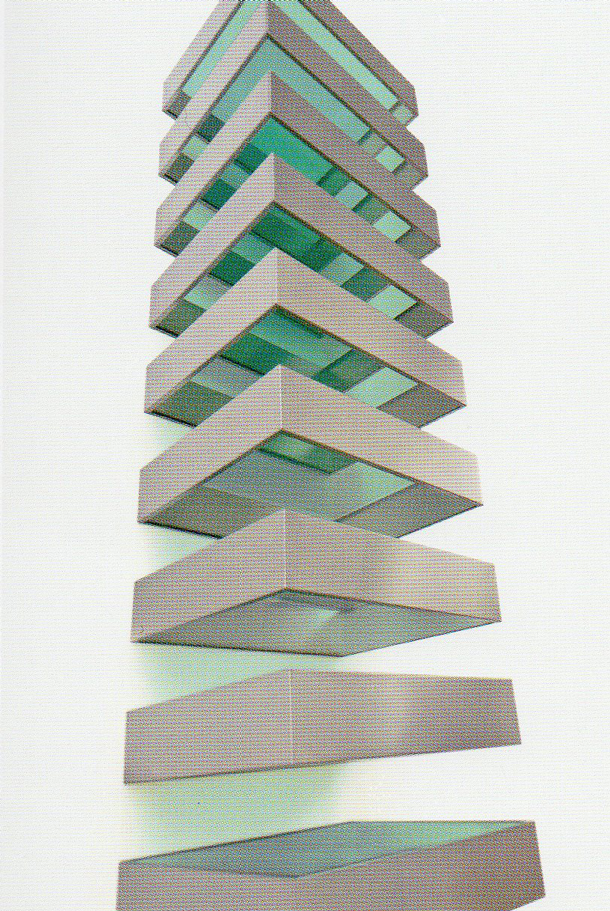

By the time of Judd’s “Untitled (Bernstein 89-1)” from 1989, the austere yet stunning stack, comprised of stainless steel and transparent green plexiglas, achieved a kind of state-of-the-art tinted aura, with its vertical majesty and remarkable light-bearing structure, creating a vista and chromatic charge within its interior color reminiscent of the Aegean Sea.

Judd’s near mythic art critical legacy further underscores his unassailable standing as “one of the most influential and profound figures of the second half of the 20th century in sculpture,” as the Tate’s Sir Nicholas Serota aptly stated on the occasion of Judd’s 2004 Tate Modern retrospective.

Ironically, Judd, who supported himself for a time as a first-rate art critic, confessed in the preface to his collected writings, “I wrote criticism as a mercenary and would never have written it otherwise.”

A striking and repetitive chord about Judd’s three-dimensional oeuvre and especially the stack pieces, that despite the industrial fabrication of the works, as if the spirit and American genius of Henry Ford were buried somewhere inside the steel sheets, it also produces a kind of cerebral music that plays inside and outside the stack forms.

Those audile impressions intensify the visual effects of the translucent, sometimes transparent plexiglas lids or dividers, in their carefully selected and stunning shades of industrial colors, and how they seamlessly adhere to the ravishing metal jacketed walls that contain, support and make them a whole.

Donald Judd, Untitled (Bernstein 89-1), 1989, (detail) stainless steel and transparent green Plexiglas, 10 units, each 6 x 27 x 24 inches (15 x 68 x 61 cm)

Looking back, it still seems remarkable that Judd’s great leap forward from paintings and wall reliefs to his more revolutionary three-dimensional work, what he famously branded “Specific Objects,” came about on the cusp of the early-to-mid 1960’s, a time of intense political and racial upheaval in America, including the turbulent transition from John F. Kennedy’s brief Camelot years to Lyndon Baines Johnson’s Great Society, the latter stained by the soon to be all-out war in Vietnam.

You don’t hear protest songs or the sonic booms of fighter jets in Judd’s epoch-making work, but all of that era is silently bound up in the DNA of Judd’s metal.

“I object very much,” said Judd in a 1989 Flash Art interview with Paul Taylor, “when my work is said to not be political because my feelings about the social system are in there somewhere. The idea is to have it all in there together—you can’t pull it out.”

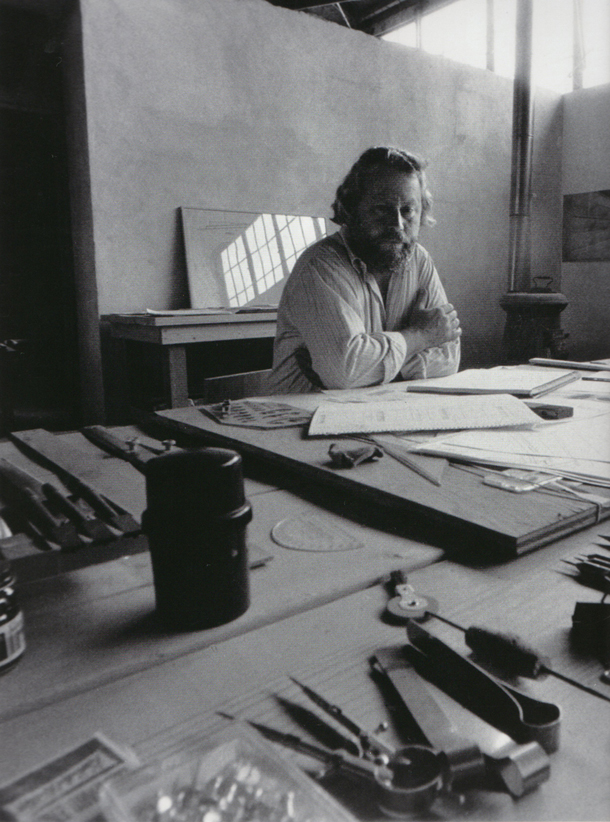

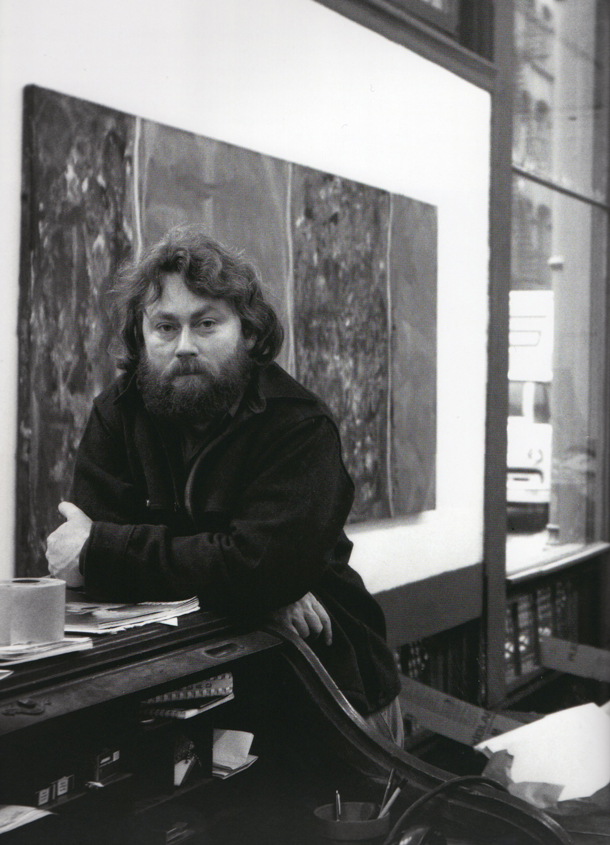

Judd at his Spring street studio, 1970