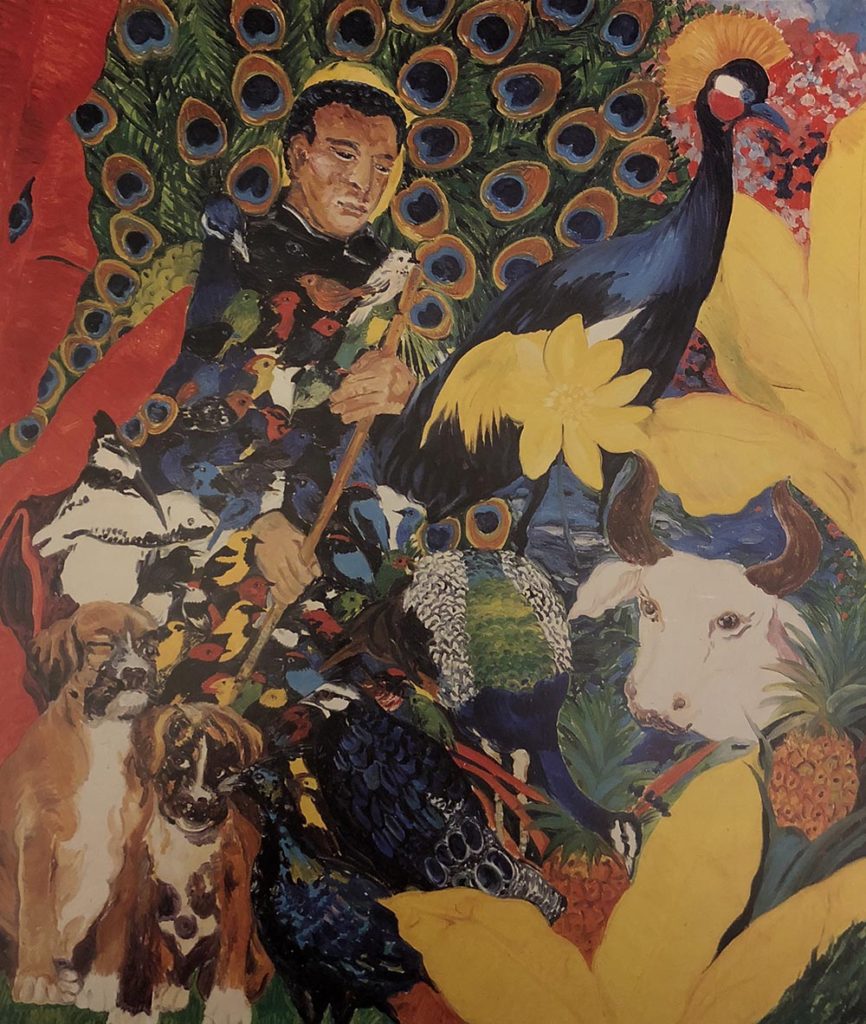

Hunt Slonem, Saint Martin de Porres, oil on canvas, 1987, 84 x 72 inches

It is hard to imagine a New York painter with a studio on the Bowery — a place where human misery and shiny restaurant equipment collide— creating a world of saints, exotic birds and enlightened yogis. A menagerie of tropical birds bathe and swing in tall cages, a screech away from the easels and paint. Their shrill cacaphony drowns out the honking traffic below. A sleek Abysinnian cat, a sleeping armadillo, and a shy hedgehog add to the riot of sounds and colors. It is a context that can’t travel, a precious physical space that frames Hunt Slonem’s paintings.

The plumage of a peacock best represents Slonem’s color sense. That and the gold paintings of Gustav Klimt, where the glit-tering chain mail of “Pallas Ath-ene” animates the canvas and banishes all notions of the ordi-nary. The peacock is a sacred bird, some say the symbol of the soul. Slonem treats color with the same reverence. It is the one element that unifies his wild mix of species with the landscape.

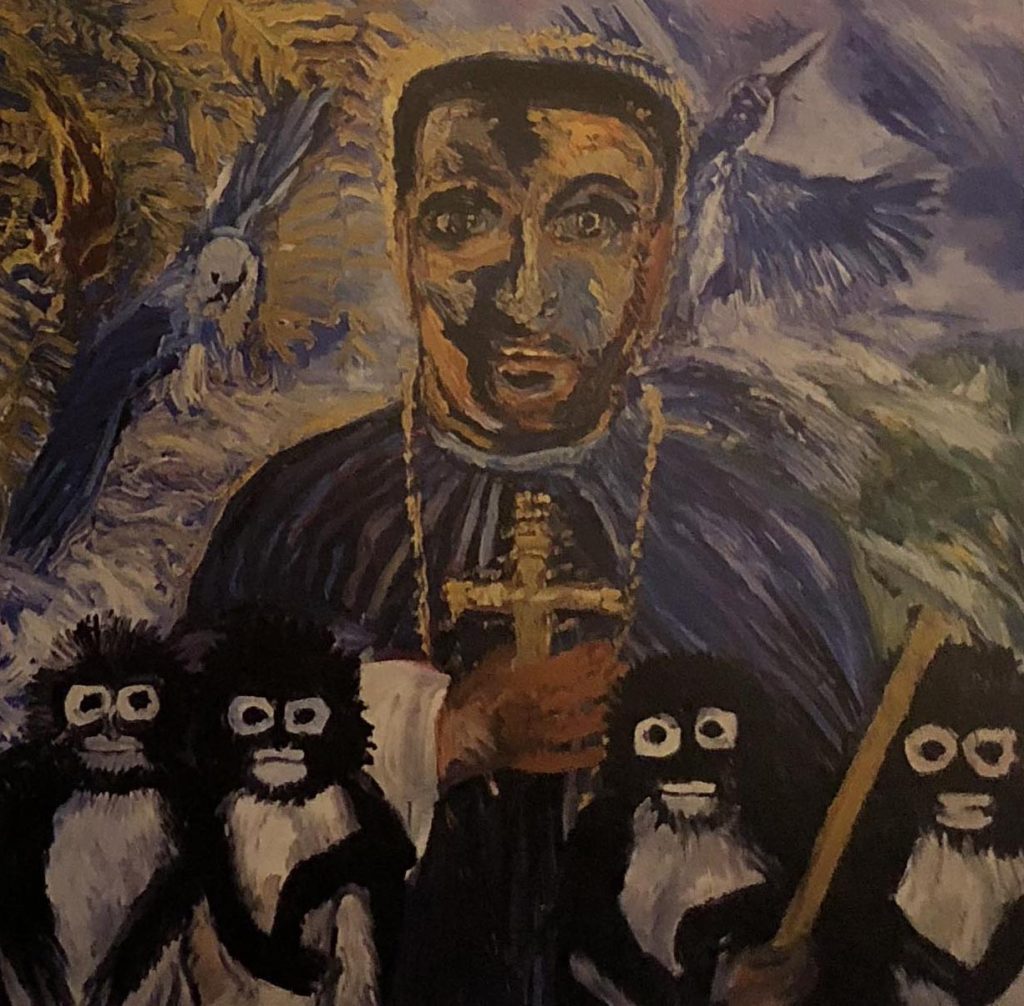

The paintings sound chocka-block and confused when you begin to describe the confluence of plants, birds, animals and human figures that occupy a shallow space that boasts the two-dimensional. No attempt is made to bring out the third. Illusory space is chucked, as in Manet. First glance readings of the pictures are stymied when you ask, “Who is that saint?” “Why is he holding a broom?” The monkeys with their white-circled eyes mock your puzzled looks as waves of fauvist color roll in. There is hardly room for a breeze. The assembly is still, collective breaths held in as if waiting for the smoky flash of an old-time camera. What is going on here?

On one level, Slonem is a story teller—a late 20th century primative with a pantheon of Christian saints. You can trace a line to the great New Mexican painter; Jose Rafael Aragon (1795-1862), and his homages in tempera and gesso on wood panels of the Virgin Mary and St. Cajetan (who worked with the poor and the sick) in Santa Fe or to the more familiar Quaker preacher-artist, Edward Hicks and his remarkable image, “The Peaceable Kingdom.” That spiritual mix of Spanish New Mexico and New England informs Slonem’s brush.

Hicks painted some sixty ver-sions of The Peaceable Kingdom. With a similar obsession,

Slonem repeatedly returns to St. Martin de Porres (the saint with the broom) who lived in Lima. Peru. from 1559-1639. So fan Slonem has painted St. Martin some thirty times. A mulatto, St. Martin nursed the African slaves and poor of Lima and also took in a menagerie of stray (logs and cats. A Dominican lay brother at Rosary Con-vent in Lima, St. Martin was reknowned for his healing powers. St. Martin has become one of the artist’s spiritual guides and major protagonists of his paintings.

Hunt Slonem, Saint Martin de Porres,

oil on canvas. 48 x 48 inches, 1984

Slonem’s rich symbolism mines the literature and oral traditions surrounding New World saints. The broom sweeps away evil and hatred, allowing a dog, cat and mouse to share the water bowl at the saint’s feet. St. Martin performed many miracles and was endowed with supernatural gifts, including bilocation and aerial flight.

A contemporary of St. Martin, the beautiful St. Rose of Lima appears in a number of Slonem’, works. She is the first saint of the New World and the garden she worked became the spiritual center of Lima. She modeled her austere rays after St. Catherine of Siena. Slonem paid homage to the tombs of St. Martin and St. Rose during a trip to Lima in 1983.

Another healer, Dr. Gregorio Hernandez, who practiced the art of psychic surgery in Venezuela, makes frequent appearances in Slonem’s paintings. Unlike St. Martin, he cuts a dapper figure in a wide lapelled suit and ever-luminous tie. His handsome, mustached face is topped by a felt brimmed hat. You never see the doctor’s hands, they are clasped behind his back. He usually stands just off center, in the midst of rich foliage and a gold-beaked Toucan. The doctor is revered in Venezuela for his power of being in two places at once. Even his death is legend. On the way to a patient, he was struck and killed by a car, the only vehicle operating in that country at the time. The bloodless surgery was successfully performed by Hernandez himself despite the indisputable facts of the accident.

There are other saints, arch-angels and faith healers in the artist’s glowing pantheon. They do not fit into the strict frame-work of the Catholic Church because the artist is not involved with nor does he believe in organized religion but creates his own meld of spiritualism. It is akin to the unorthodox approach found in James Ensor’s “The Entry of Christ Into Brussels” (1888), an epic narrative that some labeled sacriligious.

The best view of Slonem’s world is contained in an ambitious, four-panel painting, entitled “7 Saints.” The 8′ x 22′ picture could be subtitled “11 Tigers,” for these incredible creatures dominate the fore-ground, peacefully clustered at the feet of their favorite saint. Christ occupies the far left panel, a hovering force framed by the great antlers of a stag. The animal is standing on his hind legs which part illy block our view of Christ. It is an uplifting assembly, with St. Martin on Christ’s right in purple robes, Dr. Hernandez and Nino de Atocha who appeared in Spain during the Moorish conquest and fed imprisoned Christians from a single water gourd and basket of food. Dressed in red vestments and white ruffled collar, the boy is believed to have been Jesus in disguise.

Next to the boy is Kateri Tekawitha, who became known as Lily of the Mohawks and guided many of the early missionaries in the New World. Her costume of buckskin and beads clashes with Atocha’s refinements. Though she was dis-figured by smallpox as a child, the artist chooses to keep her beautiful. Her gaze is split with one eye looking out, the other inward, another sign of enlightenment. A bearded St. Francis, clasping a cross and a pair of white (loves stands between Caterine and the Virgin Mary. Two pink-crested cockatoos perch on an elephant leaf in front of the Virgin while a half dozen geese observe the extraordinary scene in spell-bound silence.

The cast of -Seven Saints” is all part of an endangered species. Tigers have been driven out of their habitats and the very junglescape is in danger of fall-ing victim to the Third World’s quest for development. In the East, tigers are considered—from their gallbladders to whiskers—vessels of great strength and courage. They are also deemed sensitive and easily insulted creatures. Gericault, Delacroix and Henri Rousseau used them for their beauty and novelty as caged creatures in a colonial world. Slonem has other ideas and they point to the East and the great continent of India. “7 Saints” is a departure, a way for the artist to bridge two worlds that are as separate as body and spirit. The beautiful green-eyed beasts protect their new found friends. Their hypnotic presence prepares the viewer for the next layer of the artist’s vision, the gods and goddesses from the 3,000 year old epic Hindu poems, The Mahabharata.

While the figures in “7 Saints” are presented in a relatively straight-forward manner, the scene in “Mahabharata” is a highly charged assault of day-glo shades and expressionist swatches that speed past even Seurat’s pointillism and push our hold on reality. Orangutans, leopards, gold-crowned warriors and a purple-skinned Vishnu celebrate Slonem’s unique vision of the miraculous. We are stripped of familiar references though the rhinoceros horn bill still prompts the Jungian interpretation of birds as the symbol of transcendence.

As in “7 Saints,” the assembly congregates for our split-second snapshot before disappearing into the perfumed air. Again we are confronted with layers of symbolism to unveil from his pantheistic brigade. It is not just gloss or a stab at recreating some Cecil B. DeMille set. The viewer has to engage the artist’s impatience for ordinary reality mapped out into rigid sections of either black or white.

The artist’s travels in Latin America, Asia and more recently, India, visiting shrines and temples parallel his insatiable collecting of exotic birds. Those distant places representing a higher state of consciousness feed into his paintings just as the extraordinary plumage of his toucans affect his palette.

If Slonem had lived in the latter part of the 19th century he might have found himself in the painterly company of the Nabis (from a Hebrew word, prophet) in France, that Symbolist circle dominated by Gauguin with Vuillard, Serusier, Maurice Denis and Paul Ranson. Ranson’s “Christ and Buddha” (c. 1890) comes very close to Slonem’s roots; in this instance, a meditating Buddha sitting in a lotus position in front of the crucified Christ. Slonem would have felt at home just as he would have with Gustave Moreau who incorporated aspects of Hindu art in his visionary paintings. The quick trip back in time is only to illustrate that the artist’s “eccentric” sensibility is in fact steeped in Western art history.

Slonem’s shift to the East creates a new vocabulary and demonstrates his insatiable quest for artistic enlightenment. As he says, “I gather up images of divine grace wherever I find them.” This duality between East and West poses a momentary problem for the viewer, much like a visitor to the Museum of Catalonian Art in Barcelona, who must decide upon entering whether to go to the left for Gothic Art or to the right for Romanesque Art. Slonem does not intend to separate his Hindu gods and god-desses from his Christian saints and healers. You quickly discover that they occupy a common ground. Lakshmi, the consort of Lord Vishnu, rose from a milky ocean, seated on lotus blossoms to dispense her blessings from a conch she holds in one of her four hands. Nino de Atocha’s gourd represents similar bounty.

The artist paints a world based on hope and beauty. It is related but opposite to Max Beckmann’s color lithograph series, “Apocalypse,” executed during the depths of World War II. Beckmann’s expressionist images were accompanied by text from Revelations, culminat-ing in the Last Judgment, depicting the judge of the world, “from whose face the earth and the heaven fled away … ”

Slonem —through the good works of St. Martin and Bhagawan Nityananda— transcends the still ticking clock of Armageddon. His light-filled canvases are, in a sense, shrines, untouched by greed or the face of death.