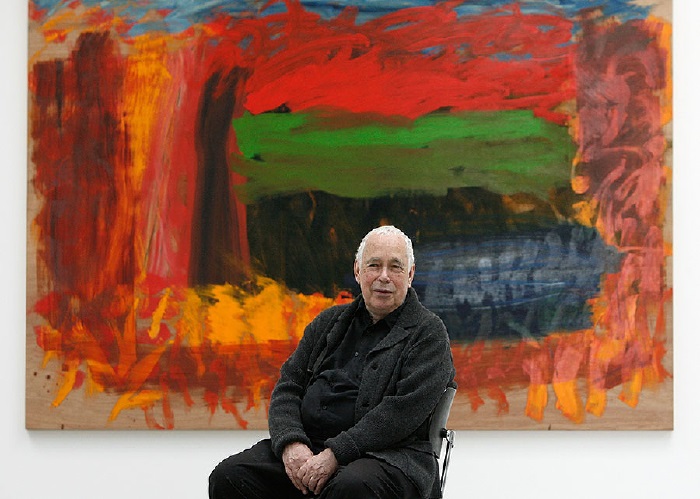

Sir Howard Hodgkin, the Tate Prize winning British painter who died last week in London at age 84 consented to an interview at his Bloomsbury studio home in 2010 for a profile in Art + Auction magazine. It was a difficult interview for me in that I had a scant hour with the great man who was obviously frail yet super-tuned to his ongoing paintings which ringed the stunning, sky lit studio, their blank backs facing out like shy ghosts. Some of his comments, really recollections about momentous times in his life, brought tears to his eyes, making it momentarily impossible for him to speak, as I sat there wondering what would come next. The way he sat, planted on a well-used studio chair, reminded me of Picasso’s powerful portrait of Gertrude Stein.

The skylit studio building, a former dairy in the days when horse drawn wagons delivered milk, is situated on a narrow side street in Bloomsbury, around the corner from The British Museum.

The lofty space is pristine and calm and apart from several worn armchairs, a cot and small side tables, it is difficult to guess what goes on here.

A handful of large, strategically placed blank canvases lean against the whitewashed walls, hiding the color saturated, precisely titled paintings that flutter between abstraction and figuration and that hang on wooden battens behind them.

It is the painting studio of Howard Hodgkin, unquestionably, one of Britain’s most important and celebrated artists, representing Britain in the 1984 XKI Venice Biennale, winner of the Turner Prize at the age of 53 in 1985, the second year it was established and knighted by the Queen in 1992.

Hodgkin, in a classic, existential retort to that knighthood, told an interviewer several years later, “I thought to hell with it. I very nearly didn’t accept it but then I thought it was taking it too seriously not to.”

Seated Buddha like in his austere studio one February late afternoon, conveying a quiet though brawny presence in his casual attire of muted grays, Hodgkin graciously, though reluctantly reminisced in spare sentences about his coming of age as an artist and the progress of his new paintings that are part of “Howard Hodgkin-Time and Place” an exhibition of work spanning from 2001-2010 that opens this month (June 23) at the Museum of Modern Art Oxford, where he had his first retrospective in 1976, curated by Nicholas Serota, a longtime champion of his work.

Nearby, a miniaturized cardboard maquette of the Oxford exhibition space, complete with tiny cut-outs of the anticipated hanging, occupied a table, indicating the ticking deadline at hand.

This fortunate visitor had already watched a number of You tube replays of several BBC interviews of the artist conducted at various times in his distinguished career and understood it would be an uphill battle to elicit much material.

“Portrait of Mr and Mrs Gahlin”, 1967 – 1969, 42 x 50 inches, 107 x 127cm

Sometime later, the prominent, Philadelphia based collector and oncologist, Dr. Luther Brady, who owns nine works by Hodgkin, including “Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Gahlin” from 1967-69 and “Heat” from 2003-04, as well as being a close friend of the artist, told me, “Howard is a very interesting person, but he’s quiet and introspective, and its hard, as you probably know, to get information out of him when you interview him.”

But luckily, it turned out not to be the case.

Talking about those early years, including several formative ones spent in New York in the 1940’s as a temporary refugee during World War II when London was being bombed and where he spent considerable time visiting the Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Modern Art where he found Matisse and Seurat, as well as Ben Shahn and Thomas Hart Benton, Hodgkin, now 77 years old, spoke of his parents’ attitude about his youthful intentions.

“They thought I was mad to want to be a painter, and they were right because there was no professional framework for being an artist in England at that time. There isn’t much now, but there was none then.”

Several times during the condensed visit, Hodgkin was overcome by emotion while describing life-changing scenes from his youth, including a time when his mother Katherine and her American friend took him out to lunch while he was at a boarding school (described by Hodgkin as a ‘Crammer’ where you cram to take exams) in Wales. He was given Gertrude Stein’s 1938 book on Picasso and in recalling its pink binding and the reproductions inside, said, “I can see it now,” and just as suddenly, lost his composure.

Referring to another important book in his literary pantheon, was one that his father Eliot Hodgkin gave him when he was a teenager, Alfred Barr’s “Matisse-His Art and His Public.”

Hodgkin explained how “Pretty much immediately, Matisse was an extraordinary influence on me. Once I got the book, I went to bed and didn’t get up for several days, until I’d read it twice.”

It’s not surprising that Hodgkin has been referred to as “Britain’s Matisse” but the jingoistic sobriquet falls short for this superb colorist, especially judging by the minimal and decidedly non-decorative elements of his studio and the obvious absence of models.

Speaking about color, Hodgkin said, “I never think about it as something separate. It’s strictly functional in my way and most people’s. It’s a very 20th century idea to separate it out and so I never have.”

Though it wasn’t on view in the studio, “Memoirs,” an early and transformative Hodgkin painting in gouache on board from 1949 came into the conversation after the artist noted it was the only one from that period still in his possession.

A seated man, crisply outlined in black, gazes intently at the reclining woman on the nearby couch, her large hands clasped on her thighs, and her head cut off by the edge of the picture plane.

The jarring composition, part German Expressionist, part Surrealist in tone, has a mesmerizing effect as you wonder what’s transpiring in this archetypal depiction of a psychoanalyst and patient at work . Or perhaps it alludes to something else.

The blood red carpet, the woman’s red fingernails and shoes clash with the seated man’s yellow pants and the menacing potted plant with the pointy leaves on a coffee table.

Most would never guess it was a Hodgkin.

According to an entry in the Hodgkin catalogue raisonne published by Thames & Hudson and compiled by Marla Price, the director of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, the scene was based on the drawing room of the Long Island home where Hodgkin was a summer house guest in the 1940’s and was the first painting to deal with the artist’s “preoccupation with remembrance.”

In speaking about his approach to making a picture, Hodgkin says, “It is amorphous, but I’m very much a subject painter. More like some 19th century artists. I don’t know how to describe what happens but I am much more in control of it than I was twenty or thirty years ago.”

Inviting his guest to look at the new work, Hodgkin remained seated and his visitor wandered over to a medium sized painting at the far end of the immaculate studio.

Noting my initial hesitation, Hodgkin said, gesturing to the blank canvases, ”I should explain immediately that these are just screens, and they often have very small pictures hidden behind them, but it’s a way of not seeing what I’m doing.”

The device is also a way for the artist to stop working on pictures which he’s known for taking several years to complete. “But until they have left the studio, or until someone buys them, they somehow are incomplete.”

Hodgkin doesn’t paint on canvas and for decades has painted on board, famously strayimg beyond the terrain of the picture rectangle to the frame, uniting the areas in an inexplicable and radical way.

Of late he prefers the backs of found picture frames for his compositions, usually the place reserved for gallery labels or the tiny holes made by framing nails or worms.

Like everything the artist makes, there’s layers of buried associations, including the biographical fact that Hodgkin used to make a living trading used picture frames he sourced outside of London and brought back for profit to the big city.

“I used to trade picture frames,” recalled the artist, “which I was obsessed by. I’m not anymore, thank God. I used to hitchhike from the country with frames. When I got to London, I’d sold them. It was a simple way of getting pocket money.”

In this work, the fancy part of the elaborate French frame was invisible, facing the wall and the artist’s armada of rich and juicy brushstrokes, containing its own elegant Morris Code of marks and dashes and punctuating slashes, consumed the antique surface in a sweeping blaze of color.

“Technicolor”, 2009 – 2010

14 1/8 x 17 1/4 inches, 35.9 x 43.8cm

Appropriately, I’m told the painting is titled “Technicolor” and instantly, other references from an earlier era rush in like a channel surfing switch to Turner Classic Movies and a time before film was digitized or painting was manipulated by Photoshop.

In an enigmatic way, Hodgkin is able to convey in his long developed, color-charged shorthand of brushstrokes, emotions that catch the viewer unguarded and vulnerable, fast enough to take one’s breath away.

The jumbo scale of the 19th century industrial space is initially jarring compared to the intimately scaled work, though the picture easily dominates the wall, kicking off a dialogue with a second, larger painting hanging nearby.

The studio setting imparted a very different impression from the one encountered last December when seven of Hodgkin’s recent, small-scaled paintings were shown at Gagosian’s Davies Street space in Mayfair, a sliver of a room. In that petite place, the voluptuously colored paintings seemed to consume all the oxygen in the rectangular room and one felt like calling in the fire department to raise an alarm.

Over the years, Hodgkin has been represented episodically by some of the world’s greatest dealers, from Arthur Tooth, John Kasmin, Leslie Waddington and Anthony d’Offay in the UK to Jill Kornblee, Andre Emmerich, Knoedler and for the last dozen years, Gagosian in the U.S. and the UK.

Asked if he was surprised by all the accolades he’s received, the largely self-taught artist replied, “It is, very. I don’t know what else it could be.”