Düsenjäger(Jet Fighter), a Gerhard Richter from 1963, slid just past its low estimate of 525 million, selling for 525.6 million on November 16 of last year at Phillips New York.

With the increasing popularity of pre-sale guarantees comes greater scrutiny

If you we’re keeping score in last November’s round of New York evening auctions, the two highest-priced lots of the week, a rare 1890-91 Claude Monet “Grainstack” painting and a 1977 Willem de Kooning abstraction, both offered by Christie’s, came naked to market-without the financial pre-auction backup of third-party guarantees or so-called irrevocable bids. Both pictures rocketed past presale expectations, with the relatively small-scale Monet spurring a 14-minute bidding war and setting an auction record for the artist at $81,447,500.

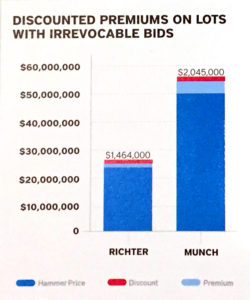

By the same token, Sotheby’s star and cover lot, Edvard Munch’s Girls on the Bridge, 1902, a picture that last sold at the same house in May 2008 for a then- record $30.8 million, sold on a single bid to the irrevocable bidder for $54,487,500-the third highest price for any artwork offered during the billion-dollar-plus week. It was undoubtedly the third party who won the Munch at the hammer price of $50 million, since the purchase price, including premium, was $2 million or so shy of what it would have been if won by an ordinary bidder.

One couldn’t make such confident claims before last September, when New York City’s Department of Consumer Affairs, the agency that oversees sales in its jurisdiction, forced the houses to report adjusted final prices on lots that carried favorable terms to the guarantor.

So what is the big to-do anyway, about the parsing out of tiny symbols printed in the back of auction catalogues that denote a guarantee is in play?”The problem with irrevocable bids is that it’s not an auction,”says David Nash, cofounder of Mitchell Innes & Nash gallery and a former longtime head of Sotheby’s Impressionist and modern department.”It is a transaction agreed in private but conducted in public and made to look like an auction.”

Speaking to the seemingly anemic Munch result, Nash observes that “there’s a sort of casino aspect to it. The irrevocable bidder might end up with the painting, or he might end up with the profit-that’s the inducement for him, anyway.”The small print in the

back of Sotheby’s catalogue affirms Nash’s perception: “The irrevocable bidder, who may bid in excess of the irrevocable bid, will be compensated based on the final hammer price in the event he or she is not the successful bidder or may receive a fixed fee in the event he or she is the successful bidder.” Nash also noted the effect of guarantees.

“It’s difficult to know how this affects the market. On the good side, it gives the world the impression that the art market is thriving. There was somebody out there who was prepared to pay $50 million, so you do have one gambler, but I don’t know how

solid that makes the market.” On the face of it, one might come to the conclusion that these individually structured guarantees dampen bidding because sophisticated players realize they might get lucky and have only a single bid to counter. In that same In that same irrevocable bid vein, Gerhard Richter’s rare-to-market “Jet” from 1963 and starring as Phillips’s cover lot from the collection of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, appeared to sell on a single telephone bid for $24 million hammer, and with fees made the top lot price of $25,565,000, on an estimate of $25-35 million. The jury is still out on whether the relatively weak price, at least compared to its estimate, was a reflection of market distaste for pre-arranged bids or a shift in interest toward the abstracts and away from the artist’s photo paintings.

Düsenjäger(Jet Fighter), once in the collection of Zero artist star Gunther Uecker, sold to Allen at Christie’s New York in November 2007 for a then-record $11,241,000.

But other issues are also at stake. “These deals work both ways,” says Frank Moore, a longtime collector based in New York.”The guarantee may affect the value of a piece negatively, or artificially positively. While it is important for the auction houses to gather material, and it is good for the seller, for buyers, it creates an artificial environment. In the past,” he continued,”it was purely about supply and demand and the wish of people who wanted to buy, and you had a real sense of value. Here, you have an artificial sense of value.”

There could be other reasons why some of the one-shot irrevocable bids registered this season appeared flat, especially for the group of 25 postwar and contemporary works from the collection of Steven and Ann Ames at Sotheby’s that, all in, made $122,777,000. “I think the starting prices were often as far as you could go with the material,” says Philip Hoffman, CEO of London’s Fine Art Group, which sometimes participates in backing irrevocable bids.”So there just wasn’t any interest in starting to compete. If we get involved in irrevocable bids, the price actually has to be a starting price rather than the price it’s going to make, because otherwise it’s a waste of time.” Hoffman was referring to the steep estimates that often accompany these third-party deals, leaving little room for extra bidding. Still, he concedes that “some collectors like the excitement of possibly making some money [from an irrevocable bid] as well the chance of owning it.”

Hoffman doesn’t see much upside for the houses in their aggressive deal making to offset the risk of putting up their own money to provide sellers with guarantees. “A lot of guarantees are given to win market share or to stop the competition from having the work or to possibly make money.” But, says Hoffman “making money seems to come second or third down the list.” Those who play in the irrevocable bid territory, he adds, “may wind up with a huge amount of art that they quite possibly didn’t want. They get tempted with the irrevocable bid.”

Still, the report card for the phenomenon of irrevocable bids also bears some high marks. Dealer Dominique Levy bought Gerhard Richter’s A B, St. James, 1988, for $22.7 million at the Ames collection sale at Sotheby’s, outgunning the irrevocable bidder.”For me,” she says, “whether or not there is an irrevocable bid doesn’t change the way I look at a picture. If it’s something I’m interested in, either for us or for a client, I look at it totally in abstraction of the financial arrangement the auction house may or may not have with a third party.”

Levy says she was surprised by the relative lack of competition for the Richter, noting it was the only “London” series picture still in private hands. She attributed the price ($20 million hammer before fees, against the $20-30 million estimate)not to its irrevocable bid butto the recent turbulence in the Richter auction market for large abstract works and the placement of the painting in the Ames sale ahead of the cover lot Richter (A B, Still, 1986), which made a more buoyant $33.9 million. “If it didn’t come first, we would have had a completely different situation,” she says.

Levy says she was surprised by the relative lack of competition for the Richter, noting it was the only “London” series picture still in private hands. She attributed the price ($20 million hammer before fees, against the $20-30 million estimate)not to its irrevocable bid butto the recent turbulence in the Richter auction market for large abstract works and the placement of the painting in the Ames sale ahead of the cover lot Richter (A B, Still, 1986), which made a more buoyant $33.9 million. “If it didn’t come first, we would have had a completely different situation,” she says.

Levy, who developed and then ran Christie’s private sales division—and at press time had just announced a partnership with Brett Gorvy, former chairman and international head of postwar and contemporary art at Christie’s—is a fan of the irrevocable bid business. “If I can be involved personally or represent a client who’s involved as a third party or negotiate a pre-sale guarantee on behalf of a client because the house, through our relationship, knows I may have someone for that picture,” she says, “I’m also going there with great pleasure.”

The business of third-party guarantees is certainly here to stay, at least as an option within the current market. “I would prefer to see the sales be more straight- forward,” says James Roundell, a partner with the dealer Simon Dickinson who previously ran the Imp/mod department at Christie’s London. Roundell’s colleague Emma Ward bought Richter’s Abstraktes Bild (720-2), 1990, which came naked to market, at Phillips this round for S6.4 million.”‘ come from an era,” he explains, “when there were no guarantees, third parties, or irrevocable bids. it was a natural market. Now it’s all ramped up to lead to one bid and it’s not at all transparent.” As Roundell sees it”We can’t all just hark back to that Golden Age. Perhaps this is the new look of the market.”