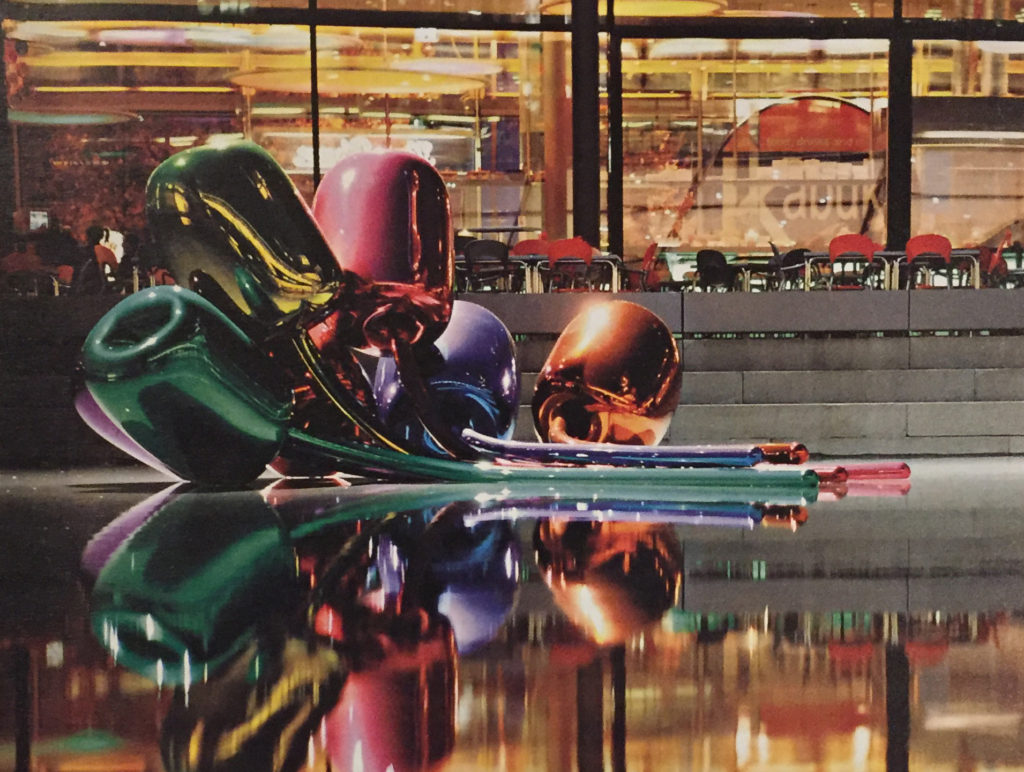

Jeff Koons’s Tulips,1995-2004, a brightly colored bouquet in high chromium stainless steel, was artfully “tossed” into the reflecting pool outside the entrance to Christie’s New York. But there was nothing casual about the price these blossoms earned: $33.7 million, an artist record

Against a sobering of global economic crises and domestic angst over threatened tax hikes for 1-percent types, record prices were achieved in the November round of postwar and contemporary art auctions in New York. The results, which edged toward the billion-dollar mark, underscore the category’s ascendance over the masterpiece drained Impressionist and modern field, as the contemporary arena increasingly attracts the players with the deepest pockets. Brett Gorvy, Christie’s chairman and international head of postwar and contemporary art, dismissed the widely held perception that Russian oligarchs and new wealth from Asia and the Gulf States are dominating high-end buying, noting, “The strongest and most consistent element of our market is the American collector.” He’s in a position to know: On November 14 Christie’s racked up $412.3 million, the highest total ever for a postwar and contemporary auction.

Eight choice Abstract Expressionist works from the collection of Sidney and Dorothy Kohl powered the results at Sotheby’s, together achieving more than $100 million, securely within the presale estimate ($84-115 million). The desirability of the Kohl paintings and works from other single-owner collections offered by Christie’s confirmed the market’s appetite for a proven connoisseur’s taste, though a third party “irrevocable bid” provided extra insurance for the Kohl Jackson Pollock, which meant it could not fail to sell. In the event, Pollock’s small, Staccato Number 4, 1951, set one of the evening’s seven artist records when it sold to a telephone bidder for $40,402,500 (est. $25-35 million). There’s no telling what a true blockbuster example could make, but at least this drip painting possesses a reassuring sales history, including a private sale through the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1969 for $22,500.

Other high achievers from the Kohl collection were Willem de Kooning’s handsome Abstraction, ca. 1949, sold to a telephone bidder for $19,681,500 (est. $15-20 million) after a round of determined bidding that included New York dealer Dominique Levy, and Franz Kline’s brawny Shenandoah, 1956, which sold to an unidentified buyer in the salesroom for a record $9,322,500 (est. $6.5-8.5 million). That record would fall the following evening, when Christie’s took its turn with a greater example by Kline.

The Kohl trove set the stage, already encouraged by the fresh coat of royal blue paint on the seventh-floor salesroom walls, for what would prove to be the most expensive work sold during the November season: Mark Rothko’s magisterial No. 1 (Royal Red and Blue), 1954. Commanding $75,122,500 (est. $35—20 million), the widely exhibited, intensely hued abstraction, from the collection of John and Anne Marion, is second in price only to Orange, Red, Yellow, from 1961, which sold at Christie’s New York this past May for $86.8 million.

After the patriarchs, it was Warhol’s night, with edgy entries from the “Death and Disaster” series and important works on paper. Straddling both categories was Suicide, 1964,a unique silkscreen print that incorporates a newswire photograph of a figure falling in a fatal blur from a high-rise building. Last sold at Sotheby’s New York in 1992, for $132,000 Suicide elicited explosive bidding and was ultimately bagged by New York private dealer Philippe Segalot for $16,322,500 (est. $6-8 million). Considering that Warhol’s Cagney, 1964, earned $6,578,500, and his The Kiss (Bela Lugosi), 1963, went for $9,266,500, the $15,202,500 Peter Brant paid for Warhol’s early and decidedly morbid Green Disaster (Green Disaster Twice), 1963, seemed a bargain.

“People are looking for trophies,” explained the preeminent Warhol collector and dealer Jose Mugrabi of Suicide, “and this was a super-trophy.” Interviewed a week after the sale, presiding auctioneer Tobias Meyer likened Suicide to Munch’s Scream, alluding to the paper substrate and disturbing subject matter and noting the “deeply intellectual” nature of the work, one “that gives you a reminder of your own mortality.” He singled out the “Death and Disaster” works as charting a new direction away from the “pleasure-seeking” buyers’ market, which pursues beauty alone.

In the relatively sparse terrain of sub-million-dollar properties, Wade Guyton’s untitled 2007 abstraction, made by feeding linen into an Epson ink-jet printer, sold for an artist record $781,500 (est. $500-700,000). No doubt the accolades won by the artist’s current mid-career survey at the Whitney Museum of American Art have markedly enhanced his market stature. The piece broke the record set just one month earlier at Sotheby’s London, where an untitled work from 2010 sold for $676,359.

After the all-time record total at Sotheby’s, the salesroom at Christie’s crackled with anticipation the following evening. The overflow audience, hoping to witness the spectacle of money spent and records shattered, was not disappointed: Seven works sold for more than $20 million each, and 55 of the 67 lots that sold hurdled the million-dollar mark. The house took in $412.3 million, racking up seven artist records and nimbly exceeding the presale $411.8 million high estimate to crush the $147.5 million result of last November. The result ranks second in Christie’s history for any category, trailing the $491.5 million

Impressionist and modern evening sale of November 2oo6, when six works exceeded $30 million, including Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II, which made a record $87.9 million. Is that category likely to retain its rank for long?

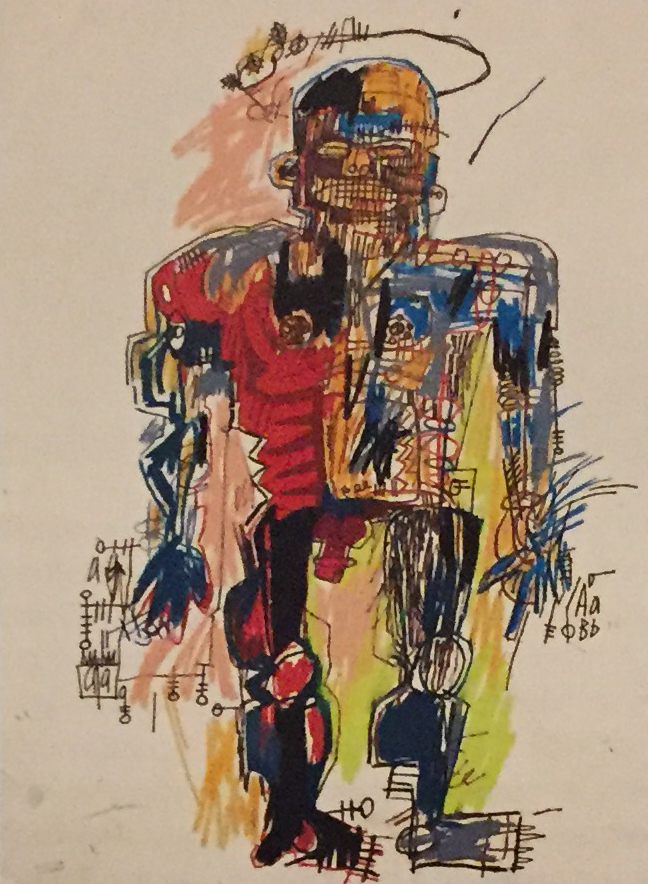

Phillips offered just 35 Lots, but the sole did not lock for record setters. The 1982 Self-Portait by Jean-Michel Basquist, right, rose past the $4 million mark to set an artist record for a work on paper

Christie’s choreographed the marathon sale with choice blocks of single-owner property, led by the Hannelore and Rudolph Schulhof collection, which made $19.2. million. Richard Serra’s Schulhof Curve from 1984, a sweep of Corten steel that the couple commissioned for their New York property, sold to an anonymous telephone bidder for a record $2,882,500 (est. $1.5-3.5 million).

A tsunami of star property hit the salesroom, as Warhol’s iconic bad-boy image, Marlon, 1966, offered by New York collector Donald Bryant, sold to Helly Nahmad, of London, for $23,714,500 (est. $15-20 million). Better known for his unrivaled Impressionist and modern inventory, Nahmad’s new interest seemed a billboard-size announcement of where the market is shifting. Bryant expressed a touch of seller’s remorse, noting, “I’ve regretted many times putting it up for sale.” Still, the collector had some fun, buying his wife, Bettina Bryant, an early Christmas present: Ed Ruscha’s Sin, 1967, a ribbonlike word in gunpowder and ink on paper, for $962,500 (est. $300-500,000), one of two works sold by Douglas S. Cramer, the storied Hollywood producer, that, together, made $18.6 million. Bryant was also the underbidder for Donald Judd’s rare copper and red Plexiglas untitled wall work of 1989 that sold for a record $10,161,500 (est. $5-7 million).

Other highlights from the generation-spanning Cramer collection were John Currin’s Gezellig, 2006, portraying a racily sprawled nude woman absorbed in a book, that sold to San Francisco dealer Anthony Meier for $2,602,500 (est. $1.2-1.8 million) and Mark Grotjahn’s colorful specimen, Untitled (Red Butterfly II Yellow Mark Grotjahn P08 752), 2008, which sold for a record $4,170,500 (est. $2-3 million), doubling the artist’s previous record at auction. Andrew Fabricant of New York’s Richard Gray Gallen, the underbidder for the Grotjahn, was candid about the superheated art market. “This is nuts,” the seasoned dealer said bluntly. “It’s some kind of weird anomaly to what’s happening in the world, and I find it sickeningly disturbing. These prices set the bar higher and higher for everyone and it completely confounds the whole model.” Fabricant wasn’t alone in damning the current frenzy: The phenomenon has been blisteringly criticized by art writers Dave Hickey, Jerry Saltz, and Sarah Thornton, the last of whom has called it quits on covering the market. It matters little to those in the game.

In this flush, competitive climate, it may not be surprising that the top lot at Christie’s was a rare curiosity: Warhol’s experimental 3-D (if you wear those throwaway glasses) Statue of Liberty. Previously obscure—Christie’s compensated by using it as a wraparound catalogue cover—the 1962, piece sold to a telephone bidder for $443,762,500 (est. on request, in the region of $30-40 million). In another indication of the ascendance of the postwar and contemporary category, the price for the Warhol is identical to that fetched the previous week by Christie’s top Impressionist and modern offering, Claude Monet’s 1905 Nympheas.

Even without the imprimatur of a named collector, classic Ab Ex was unstoppable. Kline’s powerful untitled white-and-black abstraction from 1957 sold to a telephone bidder for $40,402,500 (est. $20-30 million), obliterating the day-old record set by the artist’s Shenandoah at Sotheby’s. From the same year, Rothko’s punchy Black Stripe (Orange, Gold, and Black) sold to a telephone bidder for $21,362,500 (est. $15–zo million). It last sold at auction at Sotheby’s New York in May 1993 for $882,500. This was not a sale for bargain-hunters. It was time to cash in.

Among the record-setting lots was Jeff Koons’s over-the top ravishing, mirror-polished Tulips, 1995-2004, effectively sited in a reflecting pool outside Christie’s Rockefeller Center entrance, which sold for a whopping $33,68z,500 (est. on request, in the region of $20-30 million). The “company you keep” principle may have boosted the price: The other examples from the edition of five are in collections hearing the names Broad, Guggenheim, Pinchuk, and Prada. Later that evening, by contrast, Koons’s bosomy Beach House, 2003, sold for a limp $3,554,500 (est. $3-5 million), propped up by a third-party guarantee. Also carrying a third-party guarantee, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s widely exhibited untitled 1981 painting featuring a skeletal male figure holding a primitive fishing pole and a rather unimpressive catch, sold to the telephone for a record $26,402,500 (est. on request, in the range of $20-30 million).

If there were any surprises, one would certainly he that two of four Gerhard Richter paintings failed to sell—perhaps a result of Richter fatigue, in both market and headlines—especially since Eric Clapton’s Richter abstract made a record of 34.1 million at Sotheby’s London in October. The unrelentingly – steep climb of estimates for these works appears to be dulling some though certainly not all, appetites, you’re definitely seeing a strong concentration of collectors looking for these iconic works that bear a combination of rarity, quality, and beauty,” said Gorvy. “These are the things that are driving this market.” He added that the hunt for trophies is not “defined by specific taste or period or style, it’s very much about what is the best work out there.”

Closing out the gilded postwar and contemporary auction week, Phillips offered just 35 lots and sold a relatively modest $79,904,500, a total within the $73,620,00 to $110,730,000 presale estimate. Four artist records were set, four lots sold for more than $10 million each, and 15 exceeded the million-dollar mark.

Younger, cutting-edge artists are the house’s specialty, and that branded power was evident from the very first lot, with Tauba Auerbach’s Untitled (Fold), a trompe-l’oeil composition from 2010, selling to New York dealer Alberto Mugrabi for an artist record $290,500 (est. $200-300,000). Rashid Johnson’s darkly decorative mixed-media Fly, 2011 followed, claiming his record $182,500 from an anonymous telephone bidder (est. $100-150,000).

Next up, Sterling Ruby’s mural-scaled SP 17, 2008, sold for a record $626,500 (est. $400-600,000) to Los Angeles art adviser Julie Miyoshi of Miyoshi Art Projects. Dan C’olon’s bubble-gum-on-canvas S&M, 2010, completed the record setting quartet, selling for $578,500 (est. $200-300,000) to New York art adviser Wendy Cromwell.

For all the talk of youth being ascendant, the evening’s top lot was … Warhol’s Mao, 1973, hacked by a third-party guarantee, which sold to “a gentleman in the room,” according to auctioneer Simon de Pury, for $13,522,500 (est. $12-1 8 million). Another guaranteed Warhol, the serial “Death and Disaster” Nine Jackies, 1964, featuring the grieving and glamorous First Lady, all nine stamped “Estate of Andy Warhol” and none bearing the artist’s coveted signature, sold to a telephone bidder for $ 12,402,500 (est. $10-15 million).

Phillips seems to be drifting away from its cutting-edge roots to hunt for bigger, blue-chip game, a strategy unlikely to gain much traction against the unreachable duopoly of Christie’s and Sotheby’s. Luckily, the house had enough third-party guarantees to carry the high-end lots, including Richter’s huge abstract, Kegel (“Cone”), 1985, which sold on what appeared to he a single bid for a hammer price of $11 million, or $12,402,500 with fees (est. $12-18 million), and Basquiat’s early, oddly comical two-figure composition Humidity, 1982, which sold for $10,162,500 (est. $12-18 million). While Basquiat is no wild card, the keen interest in his works on paper was refreshing. The brashly colored crayon, felt-tip pen, and acrylic Self-Portrait, 1981, depicting a skeletal nude male with signature halo, drew at least five bidders and sold for $4,058,500 (est. $2.5 -3.5 million), a record for a Basquiat on paper. Stepping away from the usual suspects, Cady Noland’s mixed-media floor installation, Clip on Method, 1989., sold to a telephone bidder for $1,762,500 (est. $1.5-2.5 million), the artist’s third highest price achieved at auction.

The rather anemic levels of bidding at Phillips, the bridesmaid of the week, may have been a function of auction fatigue, coming at the end of a long week of evening and day sales. (In fact, Christie’s $95.9 million day sale was still going strong as Phillips started its evening auction 15 minutes late.) But taken together, the November evening sales more than upheld the strength seen in recent seasons for big-name trophy works that range across the broad postwar plains, from Kline and Rothko to Warhol and Basquiat. The question now: Whether the jaw -dropping prices realized in November will drive this deep market to greater heights—and greater expectations—in 2013