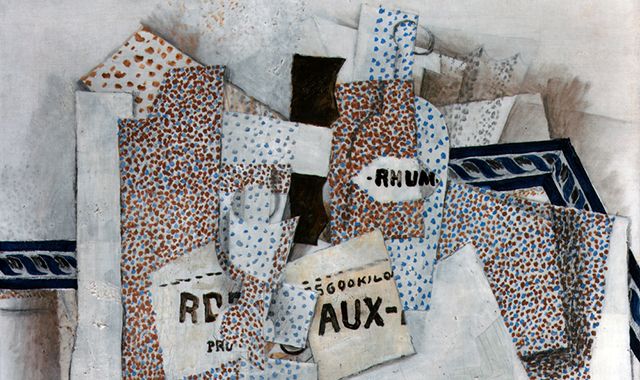

Detail of Georges Braque’s “Bouteille de rhum (Bottle of Rum),” 1914

(Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection; 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris)

Announced last week, cosmetic magnate Leonard Lauder’s extraordinary gift of 78 Cubist works to the Metropolitan Museum of Art instantly transforms the museum into a formidable citadel of modern art. The roster reads like an acquisitor’s dream, with 33 works by Pablo Picasso, 17 by Georges Braque, 14 by Juan Gris, and another 14 by Fernand Leger. Lauder’s laser-focused compilation of Cubist art masterpieces took him 37 years to assemble, according to Emily Braun, his curator of 26 years, a mission that began back in 1976 with a Leger drawing (“L’aviateur”).

Various press accounts pegged the value of Lauder’s trove at a billion dollars, without citing specific sources. One of several art market professionals contacted by ARTINFO said of the estimated value, “That’s definitely not an exaggeration.”

The lion’s share of his world-class collection was acquired privately, including an important group of paintings and works on paper from the estate of the esteemed British collector and art historian Douglas Cooper in 1986 (vetted for sale by the scholar and curator Angelica Rudenstine on behalf of Cooper’s heir and adopted son, Billy McCarty Cooper). A smaller number of key works from the gift, however, were acquired at auction, making it possible to look at their sales history.

Leonard Lauder / Photo by Mike Coppola/Getty Images

ARTINFO was able to track down three major Lauder buys at auction, beginning in November 1990 at the single-owner Estate of Henry Ford II sale at Sotheby’s New York, when Picasso’s already renowned “Verre D’Absinthe” (1914), a small, uniquely painted perforated bronze absinthe spoon that was commissioned by his Paris gallerist Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, sold for $2,530,000 (est. $800,000-1 million).

In November 1997, at the historic Victor and Sally Ganz single owner sale at Christie’s New York (the same sale where Picasso’s “Le Reve” sold to Steve Wynn for $48.4 million), Picasso’s incredibly rare “Femme assise dans un fauteuil (Eva)/Woman in an Armchair (Eva)” (1913) sold for $24,752,500 (Est. $15-20 million). It is now part of the Lauder trove.

Ganz had acquired the eroticized painting of Eva Goulet (the artist’s mistress in 1967) through storied modern art dealer Heinz Berggruen in Zurich for $158,550. Celebrated Picasso biographer John Richardson told ARTINFO that the Eva painting had previously belonged to Czech-born collector Ingeborg Eichmann, who was also a close friend of Douglas Cooper. Lauder’s acquisition of this 1913 masterpiece, therefore, is illustrative of the kinds of rich provenance his collection is imbued with. As his curator Braun noted, “Most of the pictures have exhibition histories and literature that run pages.”

Braun was also quick to head off a “misperception about the proportion of the pictures in the Lauder collection that came from Cooper’s estate,” since that purchase accounts for only five paintings and 15 drawings. “This is not somebody who bought a readymade collection,” she said. “It’s been 37 years in the making and is very disciplined and very rigorous.” By the mid-1980s — before the purchase of the Cooper trove — Lauder already owned seven major Cubist paintings, including Picasso’s “Vive la France” (1914) and Leger’s jaunty and geometric “The Smoker” from the same year. And since the Cooper acquisition in 1986, Braun says, “the collection has doubled.”

A third important Cubist work acquired at auction was Leger’s “Composition (The Typographer)” (1917-1918). At 98 1/4 by 72 1/4 inches, it is one of the largest Cubist works ever painted, and was sold at Christie’s New York in November 1998 for $6,052,500 (est. $5-7 million) — no doubt a fraction of what the work could fetch today. It had been included in the recent Leger retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art.

Lauder’s unusual single-minded love for Cubist works — virtually the opposite of his brother Ronald Lauder’s panoramic collecting taste, which ranges from arms and armor to German and Austrian Expressionism — made him a key player in this market. “He was the go-to person for Cubist paintings, if you had a good one to sell,” said dealer David Nash of Mitchell-Innes & Nash and a former head of Impressionist and Modern Art at Sotheby’s.

Lauder receives exemplary marks across the board in terms of his collecting acumen and remarkable philanthropy. “It is a superb collection,” said Richardson, the prolific Picasso biographer, “and Leonard is to be congratulated. I think its ended up in the right place. Douglas [Cooper] would be happy because he loved the Met and preferred it to MoMA.”

“In my nearly 30 years at Sotheby’s,” said David Norman, vice-chairman of Sotheby’s Americas, “I’ve never met anyone or seen a collection assembled with as rigorous and passionate a focus as this. One can learn the history of Cubism through Mr. Lauder’s collection.”

Asked about that capacity, curator Braun observed, “He’s a very keen historian and I think that his sense of history and aesthetic sense is very detailed and acute. He was attracted to it aesthetically and visually, and also understood its importance.”

The public will get its first chance to view Lauder’s Cubist legacy in its full glory in fall 2014 in an exhibition co-curatored by Braun and the museum’s Rebecca Rabinow — but if you want a taste right now, the 1913 “Woman in an Armchair (Eva)” went up at the Met this weekend, and is on view for the next three months.